IJCNC 06

Analysis and Evolution of SHA-1 Algorithm – Analytical Technique

Malek M. Al-Nawashi1, Obaida M. Al-hazaimeh1, Isra S. Al-Qasrawi1,

Ashraf A.Abu-Ein2 and Monther H. Al-Bsool1

1Department of Information Technology, Al-Balqa Applied University, Jordan

2Department of Electrical Engineering, Al-Balqa Applied University, Jordan

ABSTRACT

A 160-bit (20-byte) hash value, sometimes called a message digest, is generated using the SHA-1 (Secure Hash Algorithm 1) hash function in cryptography. This value is commonly represented as 40 hexadecimal digits. It is a Federal Information Processing Standard in the United States and was developed by the National Security Agency. Although it has been cryptographically cracked, the technique is still in widespread usage. In this work, we conduct a detailed and practical analysis of the SHA-1 algorithm’s theoretical elements and show how they have been implemented through the use of several different hash configurations.

KEYWORDS

Cryptography, SHA-1, Message digest, Data integrity, Digital signature, National security agency

1. INTRODUCTION

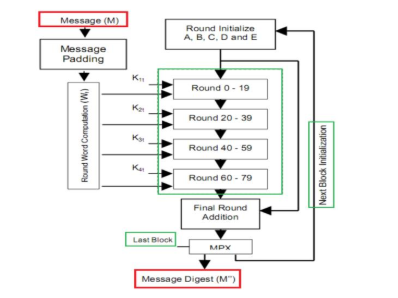

In computing, a hash function is a procedure that accepts an input of variable length and returns an output of fixed length, often called a “fingerprint.” The index into a “HASHTABLE” is a common application of such a function. Cryptographic hash functions are ideal for use in digital signature schemes and message integrity verification because of their extra features. A public key kp and a secret key ks are used in conjunction with two functions, Sign(M, ks), which generates a signature S, and Verify (M, S, kp), which returns a BOOLEAN indicating whether or not the given S is a valid signature for message M. Sign(M, Sign(M, ks), kp) = true for any given key pair (ks, kp) is a necessary condition for any function to satisfy [1-7]. Conversely, it should be unattainable to fabricate a counterfeit signature. Two sorts of forgeries can be differentiated: Universal forgeries and Existential forgeries [8-19].In the first scenario, the attacker uses the public key kp to generate a valid M, S pair. The attacker has no control over the message being computed; as a result, M is often generated at random. The attacker generates a valid signature S from the provided M and kp to establish a universal fake. Such a signature can be placed using a public-private key cryptosystem, such as RSA [20-26]. Here, the private key pair (n, d) is used to sign the message, while the public key pair (n, e) is used to authenticate the signature. Calculating the private part of the RSA key scheme efficiently enough to pull off a universal forgery is thought to be impossible. Finding an existential forgery, on the other hand, is a breeze: for any arbitrary S, we can easily determine the matching message M by solving M = Se% n. A further problem is that RSA can only sign messages up to a certain length; a simple but poor workaround would be to split the message up into blocks and sign them individually. A new message with a valid signature can be created, but an attacker can now rearrange the blocks to do so. In conclusion, the RSA method is somewhat sluggish. These issues may be fixed by using cryptographic hash functions. Such a hash function H, as was previously indicated, accepts a message of variable length as input and outputs a message digest D of defined length. A communication’s digest is now signed instead of the original message itself. It is necessary to identify message M, given D, such that H(M) = D in order to establish an existential forgery. As shown in Figure 1 [8, 27-31], the SHA-1 algorithm’s block diagram.

Figure 1. Block diagram of SHA-1 algorithm

2. SHA-1 PROCESSES – ANALYTICAL EXAMPLE

The purpose of this section is to explain the SHA-1 algorithm and its relationship to SHA-0 and SHA-2. Two distinct phases are discernible in each method, with the first being message expansion, and the second being a state update transformation that is repeated for a certain number of times (80 in SHA-1). We’ll be utilizing the “and” operator, which performs a bitwise left-to-right shift, and the “and” operator, which performs a bitwise left-to-right rotation, in the next sections [32-34]. Messages up to 264 -1 bit in length can be fed into SHA-1, and the output is a 160-bit message digest. The input is split into 512-bit chunks and padded using the following method. After appending a 1, followed by zero padding until bit 448, the length of the message is placed in the final 64 bits of the message with the most significant bits zero-padded. A sample message and the same message with some zeros tacked to the end might collide if a 1 weren’t appended first [24, 35-37]. The sections that follow will elaborate on these aspects.

2.1. Encoding

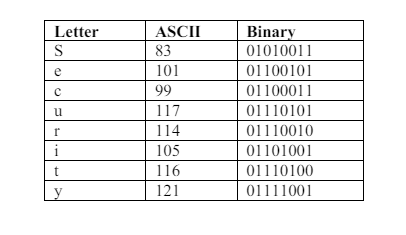

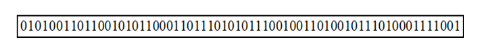

Suppose we are using the SHA-1 algorithm to encode the word “Security”. The binary representation of the word, acquired from the code as depicted in Figure 2, is indicated in Table 1. The encoded message in binary is shown in Figure 3.

Table 1. Binary encoding for messages

Figure 2. Message to binary sequence – Code

Figure 3. Binary encoded message

2.2. Padding

The following approach is used to pad the input before processing it in chunks of 512 bits. After appending a 1, followed by zero padding until bit 448, the length of the message is placed in the final 64 bits of the message with the most significant bits zero-padded. The length of our message is 64, therefore we add 383 zeroes to the end to make 484 and store the message length in the final 64 bits, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. “Chunk” 0: 512-bits in size

2.3. Splitting

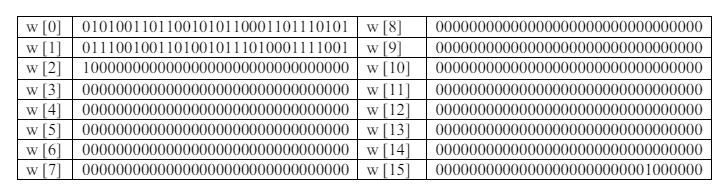

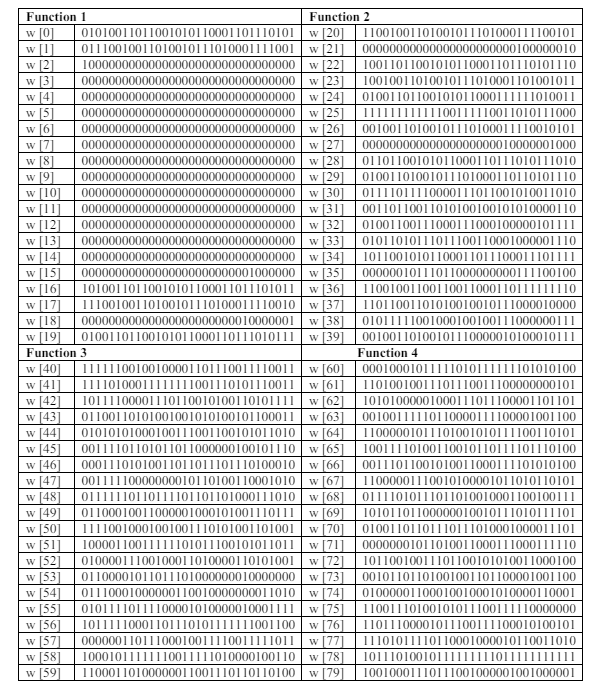

To illustrate, in Table 2 we see chunk 0 being divided into 16 words, each of which is 32 bits in size.

Table 2. Split words

2.4. Extending

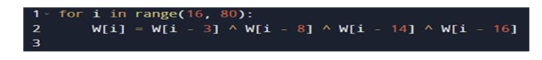

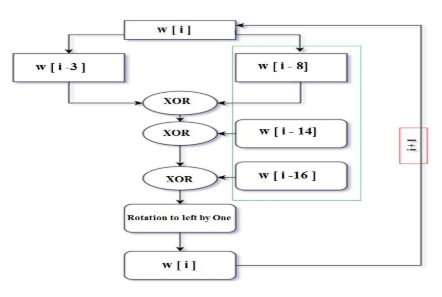

Utilize mathematical techniques based on Figure 5 and Figure 6 to elongate words into a total of eighty words.

Figure 5. Procedure expansion Code

Figure 6. Block diagram of the expansion procedures

For the sake of clarity, we’ve isolated the word number 16 in its entirety here:

w [16] = w [16-3] XOR w [16-8] XOR w [16-14] XOR w [16-16]

w [13] XOR w [8] =

00000000000000000000000000000000 XOR 00000000000000000000000000000000

= 00000000000000000000000000000000

(w [13] XOR w [8]) XOR w [2] =

00000000000000000000000000000000XOR10000000000000000000000000000000

= 100000000000000000000000000000000

((w [13] XOR w [8]) XORw [2]) XOR w [0] = 100000000000000000000000000000000 XOR

01010011011001010110001101110101

= 11010011011001010110001101110101

Left rotate by one= 1010011011001010110001101110101011

w [16] = 1010011011001010110001101110101011

Table 3 displays the 64 words formed after we iterated the techniques described above.

Table 3. Generated words

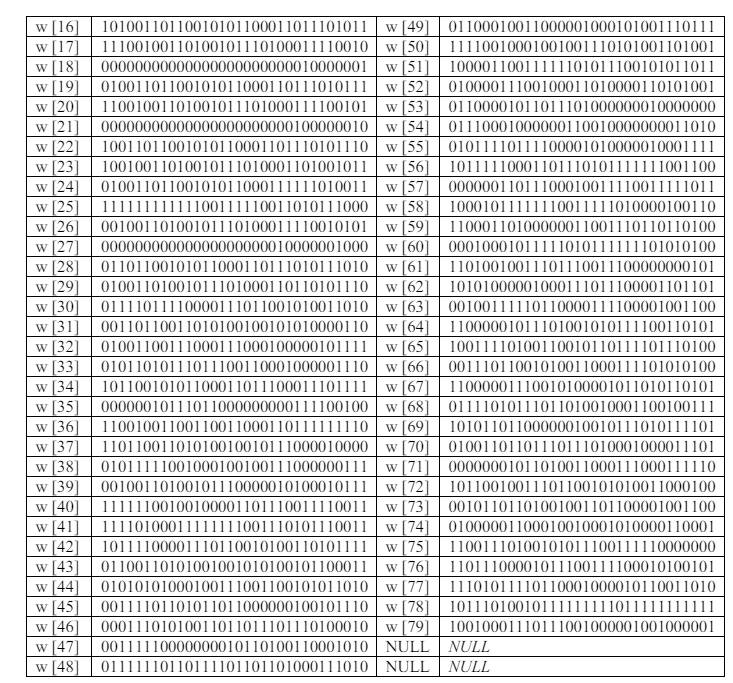

2.5. Compression Function and Constants

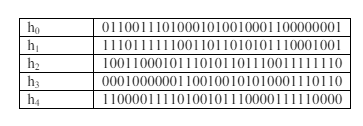

The terms from Tables 2 and 3 were analyzed, and the results were then organized into four categories (Function1, Function2, Function3, and Function4) as shown in Table 4. SHA-1 employs five 32-bit variables (A, B, C, D, and E) as the initial hash values as shown in Table 5. These primary hash values come from the decimal parts of the square roots of prime numbers and are used as constants.

Table 4. Words categories – Based Functions

Table 5. Words categories

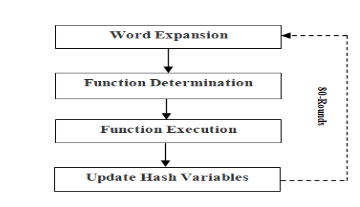

Each 512-bit block is compressed using SHA-1’s compression algorithm. There are a total of 80 iterations in the compression process, each of which operates on a single 32-bit word of the message’s schedule. Figure 7 depicts the actions that must be carried out for each round.

Figure 7. Compression algorithm

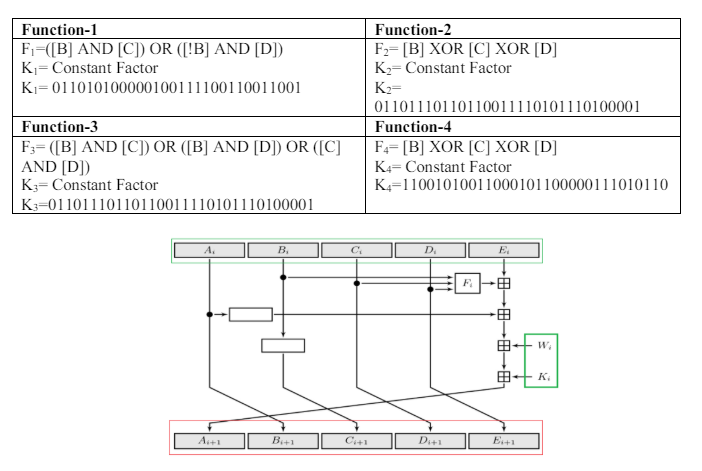

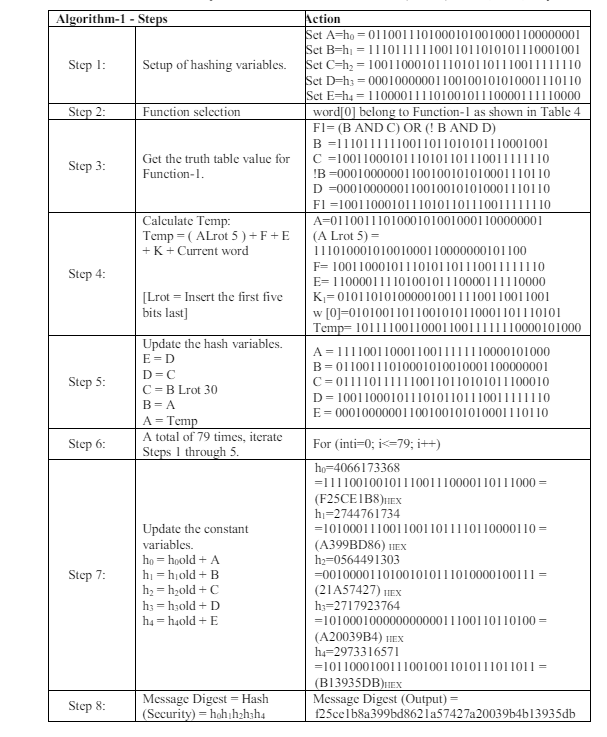

A logical operation is chosen from Function-1, Function-2, Function-3, or Function-4 depending on the rounded value as illustrated in Table 6. Then the selected function is applied to the current 32-bit word, together with additional variables and constants, utilizing bitwise AND, OR, XOR, and NOT operations. Finally, the result of the logical operation and the current word are used to modify the five hash variables (A, B, C, D, and E).The SHA-1 round operation is illustrated in Figure 8 [38-40]. To clarify, in this paper we will provide a thorough explanation of the first element of the word, denoted as word [0], in the subsequent steps (Algorithm-1):

Table 6. Function determination

Figure 8. SHA-1 round operation

Table 6. Function determination

As previously stated in this document, the hash function receives an input and generates a 160-bit (20-byte) hash value, also referred to as a message digest. The resulting value, represented in hexadecimal as “f25ce1b8a399bd8621a57427a20039b4b13935db” is equivalent to 160 bits.

3. EVALUATION

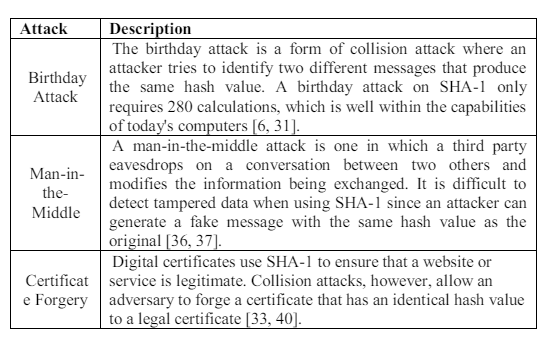

The SHA-1 hash method was long thought to be impenetrable, however it has since been found to be vulnerable to a number of attacks. It is possible to identify two different messages that generate the same hash result, which is SHA-1’s fundamental vulnerability. As shown in Table 7, this can be used in a variety of attacks [31].

Table 7. SHA-1 attacks

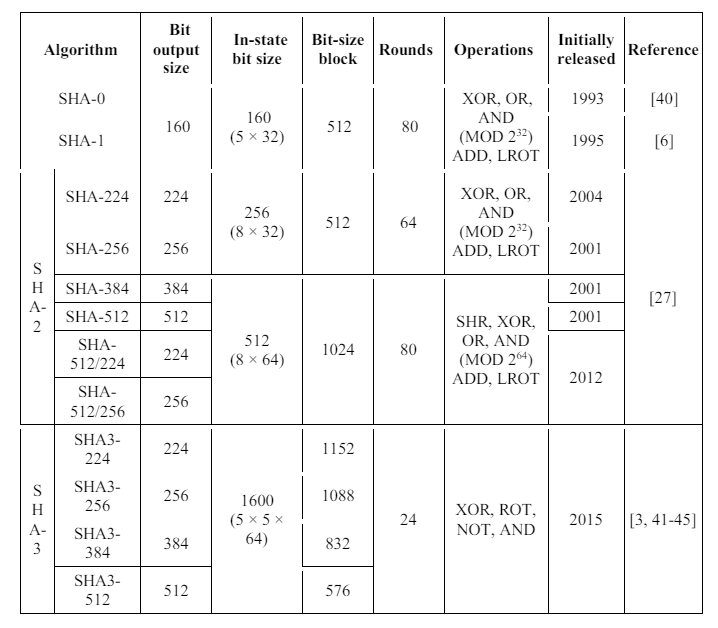

Substitutes for SHA-1, Stronger hash algorithms, such as SHA-2 and SHA-3, are recommended in place of SHA-1 because of its flaws. Table 8 shows comparisons between different SHA families. The SHA-2 family of hash algorithms generates hash values of varying lengths, from 256 bits to 384 bits to 512 bits. The successor to SHA-1, SHA-2 is often regarded as more secure. NIST developed SHA-3 in 2015, which is a more recent hash function that generates hash values in a different way than SHA-2 [41-43].

Table 8. The SHA family comparison

4. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSIONS

This paper aims to elucidate the theory of the SHA-1 algorithm, progressing from basic to advanced concepts. Our goal is to provide a practical explanation of basic mathematics and the implementation of the SHA-1 algorithm in real-world systems. Understanding this cryptographic algorithm enables comprehension of its advantages and disadvantages, facilitating the modernization and development of more efficient cryptographic algorithms.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflicts of interest. There is no financial interest and all co-authors have seen and approved the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Everyone involved in the process, from the writers to the editors and anonymous reviewers, deserves credit for the work that went into this manuscript.

REFERENCES

[1] A. Bakhtiyor, A. Orif, B. Ilkhom, and K. Zarif, “Differential collisions in SHA-1,” in 2020 International Conference on Information Science and Communications Technologies (ICISCT),

2020, pp. 1-5.

[2] E. Biham, R. Chen, and A. Joux, “Cryptanalysis of SHA-0 and Reduced SHA-1,” Journal of Cryptology, vol. 28, pp. 110-160, 2015.

[3] R. Chaves, L. Sousa, N. Sklavos, A. P. Fournaris, G. Kalogeridou, P. Kitsos, et al., “Secure hashing: Sha-1, sha-2, and sha-3,” Circuits and systems for security and privacy, pp. 105-132, 2016. [4] C. De Canniere and C. Rechberger, “Finding SHA-1 characteristics: General results and applications,” in International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, 2006, pp. 1-20.

[5] P. Garg and N. Tiwari, “Performance analysis of SHA algorithms (SHA-1 and SHA-192): a review,” International Journal of Computer Technology and Electronics Engineering, vol. 2, pp. 130-132, 2012.

[6] P. Gauravaram, A. McCullagh, and E. Dawson, “Attacks on MD5 and SHA-1: Is this the “Sword of Damocles” for Electronic Commerce?,” 2006.

[7] T. Grembowski, R. Lien, K. Gaj, N. Nguyen, P. Bellows, J. Flidr, et al., “Comparative analysis of the hardware implementations of hash functions SHA-1 and SHA-512,” in Information Security: 5th International Conference, ISC 2002 Sao Paulo, Brazil, September 30–October 2, 2002 Proceedings 5, 2002, pp. 75-89.

[8] H. Handschuh, L. R. Knudsen, and M. J. Robshaw, “Analysis of SHA-1 in encryption mode,” in Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference, 2001, pp. 70-83.

[9] J.-P. Kaps and B. Sunar, “Energy comparison of AES and SHA-1 for ubiquitous computing,” in International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing, 2006, pp. 372-381.

[10] O. M. Al-hazaimeh, “A novel encryption scheme for digital image-based on one dimensional logistic map,” Computer and Information Science, vol. 7, p. 65, 2014.

[11] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, N. Alhindawi, and N. A. Otoum, “A novel video encryption algorithm-based on speaker voice as the public key,” in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Control Science and Systems Engineering, 2014, pp. 180-184.

[12] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “A new dynamic speech encryption algorithm based on Lorenz chaotic map over internet protocol,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 10, pp. 4824-4834, 2020.

[13] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “A new speech encryption algorithm based on dual shuffling Hénon chaotic map,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, vol. 11, p. 2203, 2021.

[14] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, A. Abu-Ein, M. m. Al-Smadi, and M. H. Al-Bsool, “A split and merge video cryptosystem technique based on dual hash functions and Lorenz system,” International Journal of High Performance Computing and Networking, vol. 17, pp. 39-46, 2021.

[15] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, A. A. Abu-Ein, M. M. Al-Nawashi, and N. Y. Gharaibeh, “Chaotic based multimedia encryption: a survey for network and internet security,” Bulletin of Electrical Engineering and Informatics, vol. 11, pp. 2151-2159, 2022.

[16] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, M. F. Al-Jamal, A. Alomari, M. J. Bawaneh, and N. Tahat, “Image encryption using anti-synchronisation and Bogdanov transformation map,” International Journal of Computing Science and Mathematics, vol. 15, pp. 43-59, 2022.

[17] O. M. Al-hazaimeh, M. A. Al-Shannaq, M. J. Bawaneh, and K. M. Nahar, “Analytical Approach for Data Encryption Standard Algorithm,” International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM), vol. 17, 2023.

[18] O. M. Al-Hazaimeh and A. Ma’moun, “Vehicle To Vehicle and Vehicle To Ground Communication-Speech Encryption Algorithm,” in 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), 2023, pp. 1-4.

[19] O. M. A. Al-hazaimeh, “New cryptographic algorithms for enhancing security of voice data,” Universiti Utara Malaysia, 2010.

[20] N. Tahat, A. A. Tahat, M. Abu-Dalu, R. B. Albadarneh, A. E. Abdallah, and O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “A new RSA public key encryption scheme with chaotic maps,” International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE), vol. 10, pp. 1430-1437, 2020.

[21] O. M. A. Al-Hazaimeh, “Hiding data in images using new random technique,” International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI), vol. 9, p. 49, 2012.

[22] N. Tahat, M. T. Shatnawi, S. Shatnawi, O. Ababneh, and O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “A signature algorithm based on chaotic maps and factoring problems,” Journal of Discrete Mathematical Sciences and Cryptography, vol. 25, pp. 2783-2794, 2022.

[23] N. Tahat, O. M. Al-hazaimeh, and S. Shatnawi, “A New Authentication Scheme Based on Chaotic Maps and Factoring Problems,” in International Conference on Mathematics and Computations, 2022, pp. 53-64.

[24] R. Shaqbou’a, N. Tahat, O. Ababneh, and O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “Chaotic Map and Quadratic Residue Problems-Based Hybrid Signature Scheme,” International Journal for Computers & Their Applications, vol. 29, 2022.

[25] M. Obaida and A. Al-Hazaimeh, “A new approach for complex encrypting and decrypting data,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 5, p. 88, 2013. [26] O. M. A. Al-Hazaimeh, “Design of a new block cipher algorithm,” Network and Complex Systems, vol. 3, pp. 1-5, 2013.

[27] F. Mendel, T. Nad, and M. Schläffer, “Finding SHA-2 characteristics: searching through a minefield of contradictions,” in Advances in Cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2011: 17th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Seoul, South Korea, December 4-8, 2011. Proceedings 17, 2011, pp. 288-307.

[28] H. E. Michail, G. S. Athanasiou, G. Theodoridis, A. Gregoriades, and C. E. Goutis, “Design and implementation of totally-self checking SHA-1 and SHA-256 hash functions’ architectures,” Microprocessors and Microsystems, vol. 45, pp. 227-240, 2016.

[29] H. Michail, A. P. Kakarountas, O. Koufopavlou, and C. E. Goutis, “A low-power and highthroughput implementation of the SHA-1 hash function,” in 2005 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 2005, pp. 4086-4089.

[30] S. S. Omran and L. F. Jumma, “Design of SHA-1 & SHA-2 MIPS processor using FPGA,” in 2017 Annual Conference on New Trends in Information & Communications Technology Applications (NTICT), 2017, pp. 268-273.

[31] W. Penard and T. van Werkhoven, “On the secure hash algorithm family,” Cryptography in context, pp. 1-18, 2008.

[32] T. Polk, L. Chen, S. Turner, and P. Hoffman, “Security considerations for the SHA-0 and SHA-1 message-digest algorithms,” 2070-1721, 2011.

[33] S. Pongyupinpanich and S. Choomchuay, “An Architecture for a SHA-1 Applied for DSA,” in Proceeding of 3rd Asian International Mobile Computing Conference (AMOC), Thailand, May, 2004, pp. 26-28.

[34] V. Rijmen and E. Oswald, “Update on SHA-1,” in Topics in Cryptology–CT-RSA 2005: The Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference 2005, San Francisco, CA, USA, February 14-18, 2005. Proceedings, 2005, pp. 58-71.

[35] C. C. G. San Jose, B. Tanguilig III, and B. Gerardo, “Enhanced SHA-1 on Parsing Method and Message Digest Formula,” in The Second International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer Engineering and their Applications (EECEA2015), 2015, p. 1.

[36] N. B. Slimane, K. Bouallegue, and M. Machhout, “Nested chaotic image encryption scheme using two-diffusion process and the Secure Hash Algorithm SHA-1,” in 2016 4th International Conference on Control Engineering & Information Technology (CEIT), 2016, pp. 1-5.

[37] M. Stevens, “New collision attacks on SHA-1 based on optimal joint local-collision analysis,” in Advances in Cryptology–EUROCRYPT 2013: 32nd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Athens, Greece, May 26-30, 2013. Proceedings 32, 2013, pp. 245-261.

[38] M. Stevens, E. Bursztein, P. Karpman, A. Albertini, and Y. Markov, “The first collision for full SHA-1,” in Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2017: 37th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, August 20–24, 2017, Proceedings, Part I 37, 2017, pp. 570- 596.

[39] M. Alam and S. Ray, “Design of an Intelligent SHA-1 Based Cryptographic System: A CPSO Based Approach,” Int. J. Netw. Secur., vol. 15, pp. 465-470, 2013.

[40] X. Wang, H. Yu, and Y. L. Yin, “Efficient collision search attacks on SHA-0,” in Advances in Cryptology–CRYPTO 2005: 25th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, California, USA, August 14-18, 2005. Proceedings 25, 2005, pp. 1-16.

[41] S.-j. Chang, R. Perlner, W. E. Burr, M. S. Turan, J. M. Kelsey, S. Paul, et al., “Third-round report of the SHA-3 cryptographic hash algorithm competition,” NIST Interagency Report, vol. 7896, p. 121, 2012.

[42] S. Saraireh, “A secure data communication system using cryptography and steganography,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 5, 2013.

[43] H. Elwahsh, M. Hashem, and M. Amin, “SECURE SERVICE DISCOVERY PROTOCOL FOR AD HOC NETWORKS USING HASH FUNCTION,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 4, p. 157, 2012.

[44] I. S. Al-Qasrawi and O. M. Al-Hazaimeh, “A Pair-Wise Key Establishment Scheme for Ad Hoc Networks,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 5, p. 125, 2013.

[45] G. Li, K. T. Mursi, A. O. Aseeri, M. S. Alkatheiri, and Y. Zhuang, “A new security boundary of component differentially challenged XOR PUFs against machine learning modeling attacks,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 14, no. 3, 2022.

AUTHORS

Malek M. Al-Nawashi is a Lecturer in the Department of Computer Science and Information Technology at AL-BALQA Applied University, Jordan. He has completed his Ph.D. Degree at University of Salford Manchester in Computer Science in 2019. His main research interests are image processing and machine learning. He can be contacted at email: nawashi@bau.edu.jo.

Obaida M. Al-Hazaimeh earned a BSc in Computer Science from Jordan’s Applied Science University in 2004 and an MSc in Computer Science from Malaysia’s University Science Malaysia in 2006. In 2010, he earned a Ph.D. Degree in Network Security (Cryptography) from Malaysia. He is a Full Professor at AL-BALQA Applied University’s department of computer science and information technology. Cryptology, image processing, machine learning, and chaos theory are among his primary research interests. He has published around 52 papers in international refereed publications as an author or coauthor. He can be contacted at email: dr_obaida@bau.edu.jo.

Isra S. Al-Qasrawi received the BSc Degree in Computer Science from AL-BALQA Applied University, Jordan in 2004, the MSc in Computer Science from YARMOUK University, Jordan in 2009, she earned a Ph.D. Degree in Business Intelligence from The World Islamic Sciences and Education University. She is working as lecturer in AL-BALQA Applied University department of Information Technology. She can be contacted at email: israonnet@bau.edu.jo

Ashraf A. Abu-Ein is a Full Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering. He has completed his Ph.D. Degree at National Technical University of Ukraine in 2007. Now, he is a lecturer at AL-BALQA Applied University, Jordan. He can be contacted at email:ashraf.abuain@bau.edu.jo

Monther H. Al-Bsool received the BSc Degree in Computer Engineering from Jordan University of Science and Technology in 1998, the MSc in Computer Information Systems from Arab Academy for Financial and banking science, Jordan in 2004. . He is working as lecturer in AL-BALQA Applied University department of Information Technology. He can be contacted at email: monther.bsool@bau.edu.jo