IJCNC 08

An Efficient Federated Forcart Algorithm for Predicting and Allocating Resources in Network Function Virtualization

Kavitha.A 1 and Dr.Gobi.M 2

Research Scholar, Department of Computer Science, Chikkanna

Government Arts College, Tirupur, Tamilnadu, India.

2 Associate Professor,Department of Computer Science, Chikkanna

Government Arts College, Tirupur, Tamilnadu, India.

ABSTRACT

Network Function Virtualization (NFV) is a traditional network method, it’s replacing rigid, dedicated hardware devices with flexible, software-based virtual network functions that can be dynamically assigned and scaled across any networking infrastructure. Even though these findings give promise, still in the early stages of creating network management systems that are truly dependable, can handle massive scale, and keep sensitive information protected across different networking boundaries. While this sounds great in theory, there is a problem with how we currently use artificial intelligence to manage these systems. Traditional AI approaches, specifically reinforcement learning models, hit several problems. However, these methods often provide high computational overhead, slow convergence, and suffer from limited interpretability. In this paper, we propose a novel framework that replaces DRL with lightweight and interpretable Machine Learning (ML) algorithms. This article suggests a Federated Forcart-based NFV Resource Allocation Framework that combines a hybrid Random Forest–Cart prediction model with federated learning to address these issues. The framework supports balanced multi-metric resource optimization, precise workload prediction, and distributed knowledge exchange while maintaining local data secrecy. It maintains the parallelization strategy to minimize end-to-end latency, while significantly reducing training complexity and communication overhead. Improved prediction accuracy, decreased latency, and increased CPU and energy efficiency are demonstrated by comparison with state-of-theart methods. For next-generation NFV orchestration, the suggested method offers a scalable and private solution.

KEYWORDS

NFV, Prediction, Federated Learning, forcart, Resource allocation.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the past, network operators have provided services in the telecom sector by deploying physical, proprietary devices and equipment for each function that makes up a particular service [1][2]. Furthermore, the network topology and the placement of service pieces must take into account the stringent chaining and/or ordering of service components. These have resulted in lengthy product cycles, very little service agility, and a significant reliance on specialized hardware, especially when combined with demands for high quality, stability, and strict protocol adherence. By utilizing virtualization technology, NFV [3], [4] has been suggested as a solution to these issues, providing a fresh approach to networking service design, deployment, and management. Decoupling physical network equipment from the operations that use it is the fundamental concept of NFV. This implies that a TSP can receive a network function, such as a firewall. This enables different network functions to be virtualized on the same high –performance technology consisting of servers, switches, and storage. These can be deployed at various locations in customer sites, centralized data centers, even at the edge network also.

Network function virtualization (NFV) is still a relatively new state of affairs with many obstacles remaining to be overcome to attain the already understood benefits of the technology.[5],[6] A major challenges of NFV is to facilitate the automated management of resources allocated to VNF with service availability. Such a means of resource management is especially significant for modern day 5G networks, it will require a substantial amount of resources and provide applications such as autonomous vehicles it need-reliable network response time [7][8]. There is a demand for certain algorithms determine how much resource should be given from Network Function Virtualization Infrastructure (NFVI)to the VNFS developed such algorithms for scalable in a vertical and /or horizontal manner, alongside balancing two competing objectives.[9].However,NFV, got beneficial in many ways, It is still challenged to the extent that complicated Service Function Chains(SFC), where it’s a sequence of virtualized network functions(VNF) that are employed in the network. One of the critical challenges is to position each VNF of an SFC to satisfy the end-to-end latency constraints. The literature research different ways of decreasing SFC latencies that looked at traffic engineering, VNF enhancement, and resource partitioning and deployment. Yet these have a sequential implementation approach whereby VNFs placement are assumed to be implemented one by one.

. This simplifies the orchestration process by allowing linear optimization based on predefined Quality of Service (QoS) constraints, making the problem easier to solve deterministically. Yet, this assumption can be unrealistic in real-world NFV scenarios. Certain VNFs called as Caching and Network Address Translation (NAT),which not depend on a strict order and can be executed in parallel, significantly reducing latency. In fact, studies have shown that nearly 50% of VNF pairs can operate in parallel. These methods also depend heavily on predefined rules and lack the capability to dynamically adapt to changing network states. As a result, they fail to intelligently capture VNF interrelations and real-time resource availability, limiting their ability to make optimal decisions that maximize performance in parallel SFC orchestration.

The existing work developed framework by using Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning which tightly combined Federated Learning (FL) with Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), and performance increased in variety of applications such as online games, Network Slicing, find routing and autonomous driving etc.,[10],[11],[12],[13],[14]. The framework PVFP introduces a novel approach for parallel VNF placement in multi-domain NFV environments by combining Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) with parallelism-aware SFC decomposition. By identifying independent VNFs using dependency, position, and priority rules, PVFP decomposes SFCs into parallel and sequential segments to optimize placement. Federated learning is employed to protect data privacy while collaboratively learning placement strategies across domains.[15][16]. Although the PVFP framework effectively reduces end-to-end latency by enabling parallel VNF Placement with Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL), it exhibits several limitations that hinder its practical deployment. The implementation of DRL brings about significant computational overhead, rendering it inappropriate for environments with limited resources, such as edge NFV deployments. Furthermore, the sluggish convergence characteristics of DRL-based approaches restrict their ability to respond effectively in rapidly changing network scenarios. The framework also suffers from limited interpretability, as DRL operates as a black box, making placement decisions difficult to audit or explain. In this work, we retain the parallelism identification and decomposition principles from prior frameworks, while introducing a novel placement mechanism based on Federated Machine Learning with interpretable models.

Problem Statement

Network Function Virtualization (NFV) is extremely dynamic and unpredictable, and ensuring service continuity and Quality of Service (QoS) depends on the effective allocation of compute, memory, bandwidth, and energy resources. However, there are a number of significant issues with current resource allocation techniques, such as heuristic approaches, deep reinforcement learning, and centralized machine learning models. On the other hand, Lack of scalability and Inconsistent prediction accuracy of resource allocation when handling large, distributed NFV domains.

Contributions of this study

ML-FL-VNF framework, replace the DRL component used in previous approaches with lightweight, interpretable machine learning models, with Random Forest and CART. These models are trained locally at each NFV domain to predict optimal VNF placement, particularly focusing on parallelizable VNFs identified during SFC decomposition. The integration of tree-based algorithms enables the framework to achieve lower computational costs, faster convergence rates, and enhanced interpretability, which collectively make it more appropriate for real-time deployment across distributed NFV infrastructures.

· The Proposed ML models relate to VNFs that can run independently (with no need to run together) for which optimal placement prediction is sought. They are based on available resources, dependency states, and network congestion levels here which it determine the best placement recommendations.

· Individual NFV domains perform local training of their placement prediction models, transmitting a model updates to the global federated server independently maintaining data privacy by not sharing raw datasets. This ensures data privacy across domains while enabling collaborative learning of global placement policies.

- Compared to DRL models, Federated Random Forest and CART algorithms converge faster, require lower computational resources, and are well-suited for real-time or near-real-time VNF placement scenarios in NFV environments.

- Thus, the proposed framework, Federated machine learning closely integrates Federated Learning (FL) with Machine Learning (ML), has achieved using interpretable models for efficient and scalable parallel VNF placement prediction and resource allocations in NFV environments.

- The remaining sections are prepared as follows: Section 2 covers the literature survey, Section 3 explains the proposed methodology, Section 4 illustrates its simulation results ,Section 5 concludes the study and suggests future enhancements.

2. LITERATURE SURVEY

During the past years, many efforts have been developed to placement of SFC efficiently in networks. Three comprehensive surveys of it are given in and involving traffic scheduling, individual instantiation, parallel placement etc, considering the logic of VNF Execution, these previous efforts can be categorized as sequential, parallel &PVFP placements of SFC.

Sequential placement

It is primarily focused VNF service provisioning from a horizontal perspective, focusing on the sequential composition of VNFs and optimizing the execution of each individual component within the SFC. Given that VNF placement is an NP-hard problem,[17] numerous studies have proposed various heuristic and intelligent algorithms to tackle this challenge, with objectives such as minimizing the number of servers used, reducing resource overhead, and optimizing network traffic utilization. For instance, logarithmic factor approximation algorithms have been proposed to address VNF placement with strict ordering constraints, aiming to minimize overall service costs. Furthermore, a dual-phase heuristic method was introduced to harness traffic periodicity characteristics, aimed at reducing physical machine consumption and optimizing network resource efficiency [18]. Yet, regardless of these progress achievements, sequential placement approaches encounter difficulties in fulfilling the latency specifications of modern time-sensitive applications, particularly with extended SFC chains, due to the intrinsic limitations inherent in sequential orchestration processes [19].

Parallel placement

The aforementioned methods revolve around the practical deployment of VNF on vertical deployment lines, indicating that certain VNFs (virtual FW, virtual IDS) can also operate as one in parallel, with advanced intentions of NFV. One such advancement is the Network Function Parallel (NFP) approach which creates SFCs from new SFCs as functions are parallelized according to their dependency of function execution, and in addition, to minimize SFC delay, a combined packet processing framework known as Para Box operates amongst VNFs in such a way that packets are dynamically dispersed and parallelized within the box, merging the results according to packet order. Despite the above, many of the solutions still come as specific deployment methods and fail for parallel VNF deployment. As such, only a handful of studies support an overarching approach to parallel VNF deployment. For example, multi-instance parallel placement is a viable method as a reliability method for Data Centre Networks (DCNs) where DCNs also analyzed global methods for parallel VNF placement multiple instances, similarly, within SFCs. Other studies report limited parallelism to provide delay minimization, such as heuristics. Yet these heuristics fail to consider both the VNF interdependencies and the time-sensitive network environment that gives a context so optimization of performance for parallel SFC orchestration is restricted. For example, PVFP introduces a Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL) solution to orchestrate parallel VNFs through the integrated solutions for recognizing parallelism, latency-aware aggregation in federated and decentralized reinforcement learning for actionable, intelligent orchestration that provides contextually relevant SFC QoS through intelligent orchestration.[20]

PVFP Placement

This solution is a complex solution to the classical heuristic, parallel VNF deployment constraints enabled by Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning. This framework provides a sufficient solution that solves the constraints of conventional heuristic driven parallel VNF deployment through the utilization of Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning (FDRL). The system in question is a parallelism-aware orchestration of VNFs. First, all VNFs that can be executed simultaneously are categorized into groups based on certain factors – more specifically, inter-dependencies, placement conditions and placement priorities. Once independent VNFs are categorized into groups, PVFP leverages federated DRL to acquire placement policies in different NFV domains by only transmitting model weights instead of sensitive information.[21][22] The framework incorporates techniques such as latency/reward-based federated aggregation and flexible replay buffers to improve learning efficiency and optimize resource utilization. Simulation results from PVFP demonstrate noticeable latency reduction in SFC execution compared to sequential or heuristic-based approaches. [16]However, despite its effectiveness, PVFP still faces challenges due to the high computational overhead of DRL, slow convergence, and lack of interpretability, particularly in distributed edge NFV Domains[23][24]

Research Gap

Despite significant advancements in NFV resource allocation using machine learning, deep reinforcement learning and heuristic optimization methods face issues in poor multi metric optimization, limited generalization across distributed networks, unstable learning, high variance and centralization dependency. In addition, no prior work integrates with decision-tree with forest and federated learning for privacy-preserving, interpretable, and stable NFV resource prediction and allocation.[25] To solve these limitations, this study presents the federated forcart aimed at enhances NFV resource prediction and allocation by dynamically with scalability in multi domain environment.[26].

3. PROPOSED METHODOLOGY

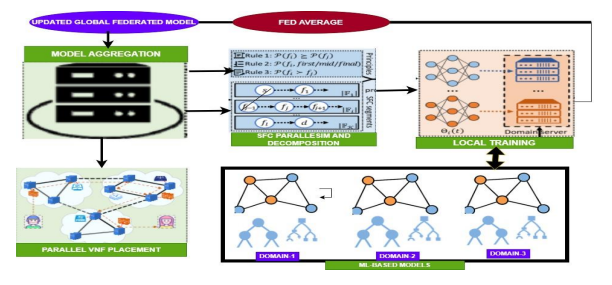

This section describes the Federated Forcart in NFV for prediction and resource allocation. Figure 1 portrays the architecture of this proposed study. This proposed study applies the proposed ML-FLVNF framework, which integrates Federated Learning (FL) with hybrid machine learning models (Forcart) for parallel VNF placement across distributed NFV domains. The work is designed to enhance orchestration efficiency while preserving privacy and improving scalability. Forcart combines the robust predictive capability of Random Forest with the transparency of cart Predictions from both models are combined, typically using probability averaging or weighted voting, to arrive at a final placement decision.[27].

Figure 1. Architecture of the Proposed Study

System Model and Problem Formulation

In this section, we present the system model, parallel SFC decomposition, and formal problem formulation for the proposed ML-FL-VNF framework, which enhances parallel VNF placement using Federated Machine Learning instead of FDRL. The key notations are listed in Table I.

System Model

We consider the physical network infrastructure as an undirected graph G = (V, E), where V represents the set of NFV nodes (e.g., servers or edge nodes), and E denotes the set of communication links between them. The network is logically divided into K federated NFV domains, such that:

Each domain Gᵢ = (Vᵢ, Eᵢ) has its own set of nodes and links and is managed by a local NFV Orchestrator, responsible for VNF placement and resource management. There is no raw data exchange between domains, only model updates during federated learning[25][26].

Similar to PVFP, each SFC request from users is composed of a series of ordered VNFs. However, parallelism rules (dependency, position, priority) are applied to determine whether portions of the SFC can be executed concurrently. VNFs that are independent of each other—such as Caching and NAT— can be parallelized to minimize latency.

The routing of a Service Function Chain is as follows

The system places each set of parallelizable VNFs across various NFV domains, taking advantage of distributed computing resources to minimize latency while maximizing resource utilization.

Problem Formulation

The objective of the proposed prediction and resource allocation algorithm is to minimize the average end-to-end latency across all service chains in the system. By summing these components, the model captures the complete latency experienced by an SFC during activation, processing, and inter-VNF communication.[27][28]

The total latency is formulated as follows

Average Latency Minimization

Minimizing this average latency ensures that the system provides efficient resource utilization, optimal placement decisions, and low delay across the entire network, rather than optimizing for only one specific service chain. This objective aligns with end-to-end QoS goals in NFV orchestration and resource allocation.[29]

The problem is defined as to maximize the following terms VNF placement constraint: Each VNF must be placed on one and only one node.

- Resource constraints: The CPU and bandwidth used by each VNF and link cannot exceed available resources.

- Flow conservation: Packet flow through intermediate nodes must adhere to flow consistency rules. PVFP, which uses FDRL-based optimization to learn placement policies.

- Lightweight machine learning models (Random Forest, CART) trained locally in each NFV domain.

Federated Learning (FL) for global model aggregation, ensuring privacy preservation. Consolidated decisions taken based on tree based structures and provide transparency than DRL-based methods.

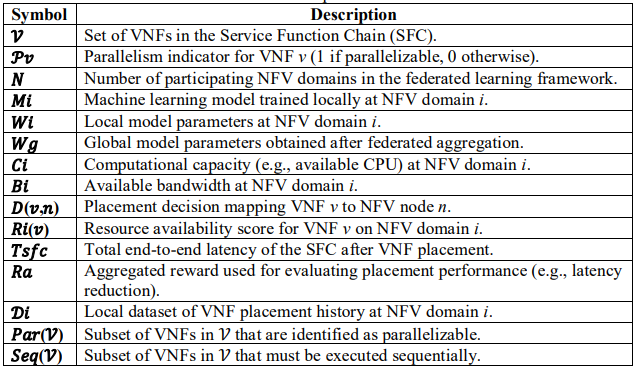

Table 1. Notations Used in the Proposed ML-FL-VNF Framework

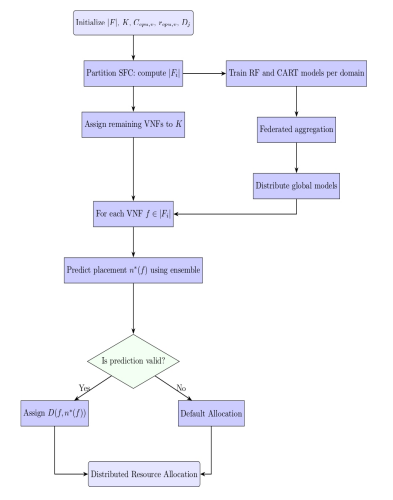

3.1. Federated Learning with Tree-Based Models

The PVFP leverages heavy DRL agents for the ML-FL-VNF, where as this proposed approach relies on more lightweight tree-based machine learning models. More specifically, Random Forest and CART are the models of choice because they can be trained over a small amount of data yet meet the intricacies of such an intricate problem. Thus, over time, each machine learning model is incrementally updated on a localized NFV domain, based on historical SFC request patterns for resources, observed patterns of resource utilization over time, and previously established placement decisions.[30] The federated learning-based structure of ML-FL-VNF, where Random Forest/CART are localized as internal trained models in different NFV domains, updated in a privacy-preserving manner in the federated learning server, and partially parallelized to facilitate decentralized VNF placement decisions.

Figure 2. Local model Resource prediction using Forcart algorithm

Each NFV domain orchestrator operates according to the federated learning (FL) framework to capture its local dataset (di). This local dataset contains all features that make up the capacity of each NFV component of interest: node CPU usage, link bandwidth availability, VNF graph structures and dependency trees, parallelization Booleans, node-link latency measurements. As these features are relatively standardized, tree-based ML-based solutions – Random Forest and CART – are trained locally, as shown in Figure (2). Random Forest is known for its reliable ensemble-based predictions after dynamic assessments of trees – and better prediction accuracy; CART is known for its speedy results explainable choices – expedited placement choices are often necessary based on SFC requests. The orchestrators learn their respective local models and only share their model weights (wi) with the centralized FL server. It’s unnecessary for the FL server to have access to sensitive raw data; instead, it can apply Federated Averaging (FedAvg) or ensemble-based averaging to the global (accumulated) findings (wg) and send this model back to the individual contributors for further learning or trusted placement operations. This assures privacy of sensitive information, reduces communication overhead, and improves convergence speed – all exponentially better than DRL-based approaches. [31][32]Therefore, when a new SFC request comes through, the expected placement of all VNFs – especially those that are parallelizable – can be anticipated through the local model or new global model in which each VNF is placed within the most suitable NFV node according to resource offering and anticipated placement history in and outside the predictive FL model; this intention reduces aggregate end-to-end latencies.

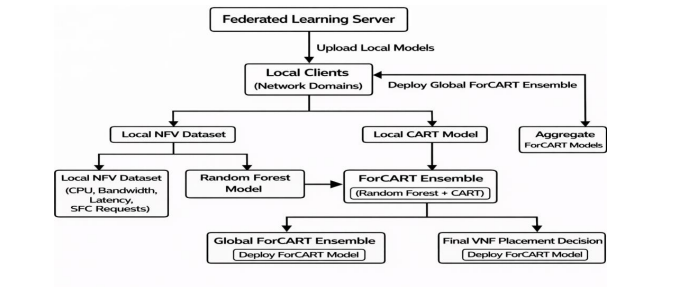

3.2. Federated Forcart based Resource prediction and allocation

The aim of the proposed Federated Forcart framework is to reduce prediction and scaling during NFV resource allocation while ensuring privacy preservation across distributed domains. Forcart combined the strengths of CART and Random Forest (RF) algorithm for a federated learning loop, it enabling stable and accurate prediction across clients without sharing raw data[33][34][35].

At each federated communication round r, client i trains a hybrid predictor using a local dataset:

Where

Di= Complete dataset stored locally at device or client i.

Xi – The input features,

yi – The target label or output value to be predicted

{⋅}- Denotes that the dataset contains multiple such input–output pairs

Each client generates two model hypotheses,

- θiC = denotes the CART parameters (splits, thresholds),

- θiR= denotes the RF parameters (ensemble trees),

- X represents the multi-metric NFV feature vector (CPU, memory, bandwidth latency, energy)

hiCART(X) = prediction produced by the CART model of client i for the input X.

fθiC(X)= the CART model function parameterized by the model parameters

hiRF(X) = prediction produced by the Random Forest model of client i for input X.

fθiR(X)= the Random Forest model function, parameterized by the set of parameters

The predicted output for a client is:

wi=The weight of client i in the aggregation.

The above Eq., takes the weighted average predictions from all clients for both CART and Random Forest, then averages the two to form a robust and accurate global prediction. This ensures the strengths of each client and model type contribute fairly to the final output.[36]

∣Di∣= number of data samples at client i.

Thus, clients with larger data volumes contribute proportionally more to the global model. It is calculated as the proportion of the client’s local dataset size ∣Di∣ to the total data across all clients.Clients with more data has higher weights, ensuring the global prediction fairly reflects all contributions[37].

Figure 3. Flowchart of Federated Forcart algorithm for prediction and allocation

4. SIMULATION RESULTS

The proposed Federated Forcart–based NFV resource allocation framework was evaluated using a high-performance workstation equipped windows with 10-64 bit and an Intel Core i7 CPU,256 GB RAM, 2 TB disk. Development and execution used Python 3.10 with Scikit-learn, NumPy, Pandas &Matplotlib. It ensures adequate computational capacity for federated model training, ensemble learning, and multi-metric resource optimization. The random seed was fixed (random state=42) for reproducibility.

Data Sets

The experiments utilized the Cloud Resource Allocation Dataset sourced from Kaggle by the following link https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/programmer3/energy-efficient-cloud-resourceallocation-dataset.It provides relevant performance metrics to evaluate the resource allocations for virtual environment, that’s are CPU utilization (%), ram (MB), network (Mbps), storage (IOPS), energy (W), latency (ms), expected load (%) and application type and processing priority. These features reflect real NFV behaviours are enough to test both regression and classification tasks.

Preprocessing

This was performed on the dataset. Initially, any NA values and outliers were removed to create a baseline of data integrity. Second, continuous integer values were normalized through z-score standardization (z-scoring) for uniform comparison across elements that may otherwise possess distinguishable differences. Categorical, discrete integer values such as type and priority were converted to integers through label encoding for machine learning processing. Finally, the processed dataset was distributed across multiple simulated federated learning nodes to mimic the reality of cloud-based environments where data is dispersed due to privacy policies, geographic barriers, and enterprise governance barriers. Table 2 represented different simulation parameters used and shows its value.

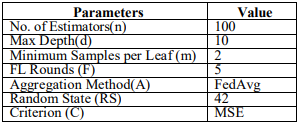

Table 2. Simulation Parameters

The information was distributed across the federated computing nodes, and each client executed data preprocessing, feature scaling and independently trained hybrid CART integrated with Random Forests. Once training was completed, clients securely forwarded their learned model weights to the central server for model aggregation and adjustment.

4.1. Performance Metrics

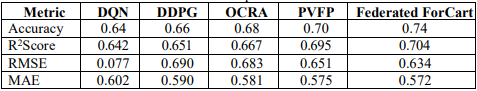

The performance was assessed based on R2, MAE, RMSE and MAPE Metrics. These measures evaluate how accurately Federated Forcart predicts the resource allocations. Table 3 represents detailed results of performance comparison with different five algorithms with different metrics.

Table 3. Performance comparisons with different metrics

According to Figure 4.1, the performance was greater than other trustable state of the art solutions. Accuracy is increased gradually from 0.64 to 0.74(Federated Forcart). R² Score represents how well the model explains variance range from 0.642 to 0.704 with Federated Forcart. The RMSE calculated for the average prediction error magnitude, it is decreased for better performance from 0.077 (DQN) to 0.634 (Federated ForCART). The Mean absolute metric measures the average size of prediction error ranges reduced from 0.602 to 0.572.

Figure 4. Performance comparisons across algorithms

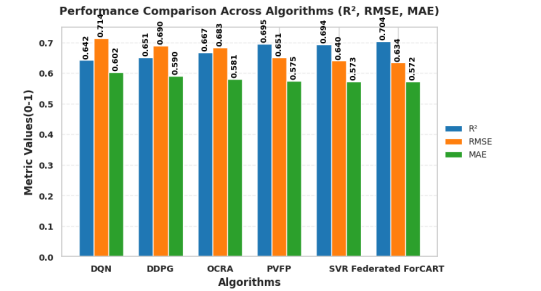

4.2. Correlation Analysis of NFV Performance Metrics

Figure 5 is the correlation matrix heatmap for the performance of NFV baseline. These details are used to represent the values between critical network parameters and interdependence between CPU Usage (%) and Memory Usage (MB), Network Usage (MBps), Disk I/O (MBps), Energy Consumption (Watts), Service Latency (ms), and Optimized Resource Management. The correlation coefficient is between -1(positive linear correlation) and +1(strong negative correlation).

Figure 5. Correlation Analysis of NFV Performance Metrics

Finally, the results of the correlation study confirm that the NFV data set is a complicated, organized one and thus, is a good candidate for federated learning and resource allocation experiments. The CPU, bandwidth and latency features are also not reliant upon each other, implying that federated learning is a suitable compromise between what is learned at each level of locality and what is learned at the network’s entirety.

4.3. Actual vs Predicted Values using Federated Forcart

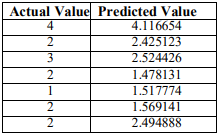

For prediction reliability, Table 4 represents variation between the actual value and predicted value. These results represents that the predictions of these values comes from trained model with time-sensitive and resource accumulating across distributed network functionalities with little prediction error and high reliability.

Table 4. Actual vs Predicted resource values

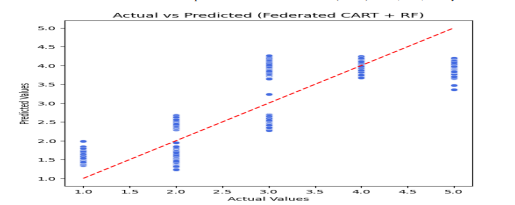

The Figure 6 demonstrate how prediction made by the model, it represented in each blue points. Meanwhile the ideal reference line (i.e.) [y=x], represented predicted values would exactly equal to actual values. This Federated Forcart’s NFV values (x-axis) against the predicted NFV values (y-axis).

Figure 6. Actual vs predicted using proposed algorithm

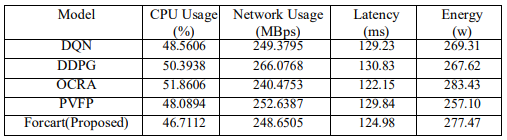

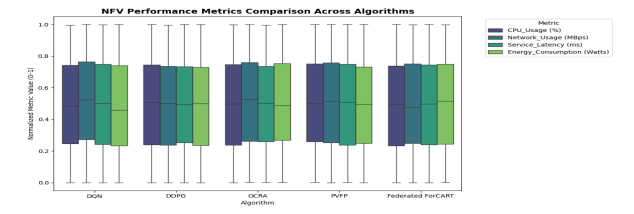

4.4.NFV Performance Metrics among various Algorithms

The Table 5 calculated the average NFV Performance metrics for each algorithm and figure 6 is a box plot. It distinguishes the normalized NFV performance metrics across the main algorithms, including DQN, DDPG, OCRA, PVFP and Federated Forcart algorithm. These summarized metrics are CPU, Network (MBps), Service Latency (ms), Energy Consumption (Watts) and usage. All the metric values were normalized from 0 to 1 to ensure a consistent scale was applied for visual and practical assessment. The IQR defines the height of the box, the line represents the median in each box and the boxes represent how far each metric deviates from the average value.

Table 5. Comparative analysis of proposed system

Figure 7. NFV performance Metrics comparison across algorithm

5.CONCLUSIONS

In this study, a new framework for parallel Virtual Network Function (VNF) placement in Network Function Virtualization (NFV) environments is introduced with ML-FL-VNF. By combining Federated Learning (FL) with the lightweight machine learning algorithms as Random Forest and CART. This suggested approach overcomes the drawbacks of current Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based techniques, especially those employed in PVFP. These solutions provides intuitive and user-friendly VNF placement decision-making with much lower DRL-computational demands and provide training times complexities. The solution is based on three main steps. First, principles of parallelism (dependency, location and priority) simplify Service Function Chains (SFCs) into serial and parallel sub-chains. Second, instead of DRL black-box models, the orchestrator of each NFV domain builds its own ML model to determine the optimal placement decision of each VNF. These proposed models are federated without sharing private information, only aggregating to a federated server, It builds a global optimized VNF placement policy. Third, VNFs are implemented in distributed NFV domains where parallel ones can run concurrently to achieve great end-to-end latency reductions. In a nutshell, ML-FL-VNF is scalable, privacy-sensitive and user-friendly for VNF placement in geographically distributed NFV domains and works best for real-time deployments in edge environments or constrained networks. In conclusion, Federated Forcart features high predictive accuracy and extensibility generalization, demonstrates that it’s a reliable VNF placement option for NFV orchestration in dynamic real scenarios. Future studies will focus on HFL to provide further cross-domain scalable low-latency service chaining for dynamic VNF placement in overloaded situations.

6.CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

[1] B. Han, V. Gopalakrishnan, L. Ji, and S. Lee, “Network function virtualization: Challenges and opportunities for innovations,” Communications Magazine, IEEE, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 90–97, Feb 2015, https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2015.7045396.

[2] Mijumbi, R., Serrat, J., Gorricho, J. L., Bouten, N., De Turck, F., and Davy, S, “Design and evaluation Algorithms for Mapping and Scheduling of Virtual Network Functions”, Network Softwarization (NetSoft), 2015, 1st IEEE Conference on, pp.1–9, 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/NETSOFT.2015.7116120.

[3] Long Qu, Chadi Assi, and Khaled Shaban, “Delay-Aware Scheduling and Resource Optimization with Network Function Virtualization”, vol. 64, issue 9, September 2016, https://doi.org/10.1109/TCOMM.2016.2580150.

[4] Akito Suzuki et al., “Extendable NFV Integrated control methods using reinforcement Learning,”, IEICE Transactions on Communications, vol. E-103-B, no. 8, pp. 826–841, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1587/transcom.2019EBP3114.

[5] Nahida Kiran, Xuanlin Liu, Sihua Wang, Changchuan Yin, “Optimising resource allocation for virtual network functions in SDN/NFV-enabled MEC networks”, IET Communications, vol. 15, issue 13, pp. 1710– 1722, April 2001, https://doi.org/10.1049/cmu2.12183.

[6] J. Zhang, Z. Wang, C. Peng, L. Zhang, T. Huang, and Y. Liu, “RABA: Resource-aware backup allocation for a chain of virtual network functions,” IEEE Conference on Computer Communication, June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOM.2019.8737565.

[7] M. Peuster, S. Schneider, and H. Karl, “The softwarised network data zoo,” IEEE/IFIP CNSM, 2019, pp. 1918–1926. http://dl.ifip.org/CNSM.2019/1570555677.

[8]Zhiyuan Li, Lijun Wu, Xiangyun Zeng, Xiaofeng Yue, Yulin Jing, Wei Wu, and Kaile Su, “Online Coordinated NFV Resource Allocation via Novel Machine Learning Techniques,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 20, no. 1, March 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2022.3205900.

[9]L. Wang, Z. Lu, X. Wen, R. Knopp, and R. Gupta, “Joint optimization of service function chaining and resource allocation in network function virtualization,” IEEE Access, vol. 4, pp. 8084–8094, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2629278.

[10] R. Mijumbi, S. Hasija, S. Davy, A. Davy, B. Jennings, and R. Boutaba, “Topology-aware prediction of virtual network function resource requirements,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 106–120, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2017.2666781.

[11] N.He et al., “Leveraging deep reinforcement learning with attention mechanism for virtual network function placement and routing,” IEEE Trans. Parallel Distribution Systems, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 1186–1201, April 2023, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2023.3240404.

[12]D.Li, P. Hong, K.Xue, and J. Pei, “Virtual network function placement considering resource Optimization and SFC requests in cloud datacenter,” IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol.29, Issue No.7,01 July 2018 ,pp.1664–1677. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPDS.2018.2802518.

[13] H. Thakkar, C. Dehury, and P. Sahoo, “MUVINE: Multi-stage virtual network embedding in cloud data centers using reinforcement learning-based predictions,” IEEE Journal on selected areas in communications. vol.38, issue no.6, pp.1058–1074, June 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSAC.2020.2986663.

[14] J. Luo, J. Li, L. Jiao, and J. Cai, “On the effective parallelization and near-optimal deployment of service function chains,” IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 1238– 1255, May 2021. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2021.3074086.

[15] I.-Chieh Lin, Yu-Hsuan Yeh, and Kate Ching-Ju Lin, “Toward optimal partial parallelization for service function chaining,” IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 2033– 2044, Oct. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNET.2021.3075709.

[16] C. Sun, J. Bi, Z. Zheng, H. Yu, and H. Hu, “NFP: Enabling network function parallelism in NFV,” ACM SIGCOMM, pp. 43–567, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1145/3098822.3098826.

[17] Haojun Huang, Jialin Tian, Geyong Min et al., “Parallel placement of virtualized network functions via Federated Deep Reinforcement Learning,” , IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, pp. 1–14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNET.2024.3366950.

[18]J. Chen, J. Chen, R. Hu, “MOClusVNF: Leveraging multi-objective for scalable NFV orchestration,” CCIOT 2019, pp. 27–33, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1145/3361821.3361837.

[19] Mahsa Moradi, Mahmood Ahmadi, Atif Pour Karimi, “ Virtualized network functions resource allocation in network functions virtualization using mathematical programming,” Elsevier Computer Communications, Dec. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comcom.2024.107963.

[20]R. Cohen, L. Lewin-Eytan, J.-S. Naor, and D. Raz, “ Near optimal placement of virtual Network functions,”IEEE INFOCOM 1346–1354,2015. https://doi.org/10.1109/INFOCOM.2015.7218511 ..

[21] S. Selvi, S. Ganesan, “ An Efficient Hybrid Cryptography Model for Cloud Data Security,” IJCSIS, vol. 15, no. 5, May 2017. ISSN 1947-5500. https://sites.google.com/site/ijcsis/ISSN 1947-5500,

[22]Ali Nouruzi, Abolfazl Zakeri, Mohamad Reza Javan, Nader Mokari, Rasheed Hussain, Ahsan Syed Kazmi, “ Online Service Provisioning in NFV-enabled Networks Using Deep Reinforcement Learning,” Systems and Controls, Nov 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2111.02209.

[23]Hudson Henrique de Souza Lopes, Lucas Jose Ferreira Lima, Telma Woerle de Lima Soares, Flávio Henrique Teles Vieira, “Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Based Resource Allocation Considering Network Slicing and Device-to-Device Communication in Mobile Networks,” Sensors 2024, 24(18), 6079. https://doi.org/10.3390/s24186079.

[24]Gil Herrera, Botero, “Resource Allocation in NFV: A Comprehensive Survey,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 13, issue 3, Sep 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2016.2598420.

[25]Zhiyuan Li et al., “Online Coordinated NFV Resource Allocation via Novel Machine Learning Techniques,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 20, no. 1, March 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSM.2022.3205900.

[26] Uma Maheswara Rao, JKR Sastry, “Enhanced Feature -driven Multi-Objective Learning for Optimal Cloud Resource Allocation (OCRA),” Soft Computing & Artificial Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 3, 12 April 2024. https://doi.org/10.12694/scpe.v25i3.2689.

[27]S. Selvi, M. Gobi, M. Kanchana, S. F. Mary, “Hyper elliptic curve cryptography in multi cloud- security using genetic techniques,” ICCMC, IEEE, pp. 934–939, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCMC.2017.8282604.

[28] Selvi S, Gobi M, “Hyper elliptic curve based homographic encryption scheme for cloud data security,” ICICI 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03146-6_7.

[29]Vishal V, S. Selvi, “ZPHISHER TOOL IN CYBER SECURITY,” International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science, vol. 6, no. 12 December 2024. ISSN 2610–2612. https://www.scribd.com/document/858555763/fin-irjmets1734768076

[30]Lavanyan T, Selvi S, “Quantum computing: A threat to Cryptography,” International Journal of Research Publications and Reviews, vol. 5, no. 12,PP.3867- 3874, December 2024. https://ijrpr.com/uploads/V5ISSUE12/IJRPR36596.pdf

[31] S. Shaathvi, S. Selvi, “Transforming Social Media Marketing using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning,” International journal of innovative research in computer and communication engineering, vol. 12, no. 12, 2024.https://doi.org/ 10.15680/IJIRCCE.2024.1212045.

[32]A. M. Medhat, et al., “Management of Virtualized Next Generation Networks”, International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 7, no. 6, November 2015, https://ijcnc.com/nov7615cnc01/.

[33]S. Dutta and S. De, “Flexible Virtual Routing Function Deployment in NFV-based Networks”, IJCNC, vol. 8, no. 5, September 2016, https://aircconline.com/ijcnc/V8N5/8516cnc02.pdf.

[34]M. T. Beck, et al., “Dynamic Shaping Method using SDN and NFV Paradigms”, IJCNC, vol. 13, no. 2, March 2021, https://manuscriptlink.com/cfp/detail/journal/LGDLWVMT54180148J.

[35]G. Xilouris, et al., “Management of Virtualized Next Generation Networks”, IJCNC, vol. 7, no. 6, November 2015, https://airccse.org/journal/ijcnc.html.

[36]Aziz Ullah Karimy& P. Chandrasekhar Reddy, “Enhancing IoT Security: A Novel Approach with Federated Learning and Differential Privacy Integration,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC),vol.16,no.4,2024.https://aircconline.com/abstract/ijcnc/v16n4/16424cnc01.html

[37]Pham Hoai An et al., “Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation in Massive MIMO NOMA Systems,” International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), vol. 17, no. 6, 2025, https://aircconline.com/abstract/ijcnc/v17n6/17625cnc01.html

AUTHORS

Kavitha A. is a Ph.D. research scholar at Chikkanna Government Arts College, Tirupur. She holds an MCA and an M.Phil. degree. Her research interests include computer networking, and she has published research articles in reputed journals and presented her work at national and international conferences. She is passionate about teaching and mentoring students.

Dr. Gobi M. serves as an Associate Professor at Chikkanna Government Arts College, Tirupur. He holds MCA, M.Phil., Ph.D. degrees, all awarded by Bharathiar University. With over 29 years of teaching experience, he has published research papers in reputed international journals and has served as a reviewer for several computer science journals. He has presented and participated in numerous national and international conferences and has acted as a resource person for various academic institutions.