IJCNC 03

RLSUAV: RELATIVE LOCALIZATION IN A SWARM OF UAVS

Sara Benkouider, Nasreddine Lagraa, and Mohamed Bachir Yagoubi

Laboratoire d’Informatique et de Mathématiques, Université Amar Telidji de Laghouat,

Laghouat, Algeria

ABSTRACT

A swarm or fleet of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) can be used to accomplish several missions such as security, search and rescue or surveillance in unknown and dangerous environments. In order to deploy a fleet of drones for such applications, drones must be able to perform certain tasks, such as collision prevention, and formation flight with a leader node. These tasks are accomplished by knowing the location of neighboring drones in the group. The conventional method of determining the position relies mainly on the GPS system. Therefore, drone swarms relying on classical positioning methods (GPS) cannot operate in dense urban or in indoor environments, due to the difficulties encountered in receiving the GPS signal from the satellites. In these cases, relative localization can be used to help nodes without GPS to determine their positions. Relative localization uses cooperative communication and information sharing between nodes in the network to help them estimate their positions. In this paper, we propose a novel technique providing relative localization in a swarm of UAVs (RLSUAV) that does not require any GPS information and, therefore, can be used in indoor environments. It consists of estimating the positions of the drone nodes as a function of the distances measured between them, combined with the multilateration technique, where the distances between the drones are calculated using the power of the received signal (RSSI). Simulation results showed the effectiveness of RLSUAV in different environments (with and without multipath), achieving an estimation error inferior to 5 meters in most cases

KEYWORDS

UAV; Swarm; Relative localization; GPS; Indoor environment; Multilateration; RSSI; Multipath

1. INTRODUCTION

This document describes, and is written to conform to, author guidelines for the journals of AIRCC series. It is prepared in Microsoft Word as a .doc document. Although other means of preparation are acceptable, final, camera-ready versions must conform to this layout. Microsoft Word terminology is used where appropriate in this document. Although formatting instructions may often appear daunting, the simplest approach is to use this template and insert headings and text into it as appropriate.

A drone or Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) designates an aircraft without a human pilot on board, which can be remotely controlled from a ground station. A ground station refers a set of physical entities and software (Ground Control Station (GCS)) that keeps track of the movement of drones. Depending on the type of station used, it can be equipped with a human-machine interface that allows the ground operator to monitor the position of a drone in real time [1].

Drones are generally used for reconnaissance or surveillance missions where they collect multiform information from objectives on the ground, and then transmit their images or other data by wireless links. In order to improve the performance of drones on these missions, research is being carried out to make drones cooperative [2]. A fleet of cooperative drones would then be able to carry out more complex missions more quickly by sharing different tasks between them. For example, surveillance of an environment might require updates of every movement detected after office hours. A large environment would require a lot of manpower for thorough manual surveillance. Contrary to this, a swarm of drones can cover and monitor the region much more efficiently with a minimal manual effort by automatically and quickly sending an alert to the ground station upon detection of movement [3]

In order to establish communication in a fleet of drones, different communication architectures can be distinguished [1, 4, 5]:

• Centralized communication architecture: In this architecture, each drone is directly connected to the ground station to transmit data and to receive the command and control flow. Drones cannot directly connect to each other, which requires going through the ground station.

• Cellular communication architecture: This architecture is based on the use of an infrastructure of ground stations and groups. In each group, we can find a subset of drones and a ground station that manages the group. Inter-group communication must go through the ground station; on the other hand, direct intra-group communication can be established.

• Satellite communication architecture: In this architecture, the satellite functions as a communication relay. Its receiving antennas receive the signals transmitted from the ground station; these signals are then retransmitted to the drones. The use of satellites provides more effective coverage than that of centralized communication. Yet, it still requires satellite routing and, if there are obstacles around the ground station, communication to the satellite can be partially attenuated or completely blocked.

• Ad hoc communication architecture: It is a completely decentralized architecture where drones are able to self-organize without the need for a fixed infrastructure. If a transmitter is not within direct range of the destination, the information is transmitted hop by hop, along the established path.

In a swarm of UAVs, the ad hoc architecture has several advantages over other types of architecture. For example, if there are obstacles, it is possible to form a chain of drones which could avoid the obstacle. In addition, self-organization allows drones to search for an alternate path in the event of a loss of a link, and to move freely and arbitrarily depending on mission objectives.

The use of drones has increased dramatically due to remarkable advancements in technology. They have become the preferred choice for various applications such as search and rescue missions in dangerous situations, military missions, cooperative aerial photography and agricultural surveillance, etc. In order to deploy a swarm of drones for such applications, certain tasks must be performed, such as preventing collisions between drones, and achieve formation and swarm flight. These tasks are accomplished by knowing the relative location of all nodes in the network. However, knowing the precise location of all the nodes in a swarm of drones is one of the most important requirements to use in any application. In outdoor missions, Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers can be used to obtain a global position, which is then shared, but this does not work well in indoor missions.

In indoor missions, relative localization techniques that do not require any GPS information have been proposed to estimate positions. Relative localization makes use of communication and information sharing among nodes in the network to assist nodes without GPS to find their localization [6]. It has also been demonstrated that relative localization may further increase the

localization accuracy when GPS is available to all the nodes. This is due to the sharing of additional information made available to the nodes. Therefore, cooperative localization not only aids nodes without GPS in localization, but also helps to improve the accuracy of all the nodes in the network [7].

Relative localization has been used primarily in ad hoc networks [8, 9], wireless sensor networks [10-14],and vehicular ad hoc networks [15-18], but recently a number of solutions have been proposed for UAV ad hoc networks [19-24].

In this paper, we propose a new relative localization technique aimed at establishing node positions in a swarm of UAVs. It is based essentially on a technique of establishing the relative positions of nearby nodes as a function of the measured distances between drones in an indoor environment where no GPS information is available. The distances between nodes are calculated using the received signal strength indication (RSSI). Mathematical analysis and simulations were performed to demonstrate the effectiveness of our technique. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The existing related works are summarized in the following section. In Section III, our proposed method of relative localization in UAVs swarms is presented. Afterward, simulation results are discussed in Section IV. Finally, Section V includes the conclusion and refers to future work.

2.RELATED WORKS

The main advantage of drones (UAVs) that make them useful in many application areas is their ability to be self-programmed to perform tasks. In this context, localization is one of the critical modules of autonomous drones for the execution of automated tasks. When targeting outdoor environments, autonomous flight planning is less difficult, as the positioning module is based on global positioning systems (GPS), which are quite reliable for positioning and navigation. However, in indoor environments, the GPS service is not available, or it is not sufficiently reliable and accurate.

The problem of UAV positioning in indoor environments has been studied in recent years. Depending on the measures used, the techniques proposed in the literature can be classified into three groups:

- Techniques based on the measurements of the devices on board each drone (camera, INS,

Bluetooth etc.); - Techniques based on measurements of equipment installed in the environment (Wireless

Fidelity (Wi-Fi), Ultra Wide Band (UWB)); - Hybrid techniques that combine the two groups.

In order to solve the collision problem in a swarm of UAVs in indoor environments, a novel relative localization system has been proposed in [25]. The proposed system exploits the communication between drones to exchange the following states: the speed of the drone in space, its orientation relative to the north, and its height above the ground. With Bluetooth communication, a drone can measure the received signal strength (RSSI) indicating the relative distance to other drones. Each drone fuses the received states from its neighbors containing RSSI information with its own built-in states (using the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF)) to get a relative estimate of the location and movements of all other drones.

Other relative localization methods have been proposed which are based on visual information [26, 27]. For example in [26], the authors proposed a cooperative localization system for UAV ad hoc networks using vision-based information detection. In this work each drone is equipped with a camera to detect its environment, and to estimate the relative positions between them using multi-view geometry. The downside of using only one camera for each drone is that the angle of view is limited; therefore, the localization system cannot provide relative position measurements between all the drones.

To this end, in [27], the authors proposed to integrate information from an on-board camera module with data from the inertial navigation system (INS) to provide the relative positions of all drones. However, such approach quickly accumulates position errors, where the error can reach up to 1.4% of the total distance traveled [28].

Solutions based on visual information are generally very slow, consume more power, and require appropriate recognition algorithms. On the other hand, the use of measurements derived from signals such as Ultra Wide Band (UWB), or signals from access points, in localization systems targeting both urban and indoor environments, is able to achieve better results. UWB can also be used for positioning mobile nodes, where the UWB beacons would emit data, which are then received by nodes in the environment. The latter approach evaluates the distance of the beacons by measuring the propagation time of the signals, which makes it possible to calculate their positions using the trilateration technique.

In order to achieve indoor localization of the drones, base stations were used in [19]. This system uses the Time Difference of Arrival technique (TDoA) to measure the distance between the drones and the four base stations installed in the four corners of the deployment area. As the TDoA measurement model obtained is nonlinear, the position of a drone is estimated using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF).

Another localization system based on access points is proposed in [20] for UAVs in indoor environments. It is based on the distance measurements between drones and an infrastructure consisting of Wi-Fi access points, with locations known a priori. The locations of the WiFi APs can be anywhere in the 3D space, without any restrictions. In this localization system, the access points periodically broadcast their positions; each drone stores the positions of the access points and calculates its position based on the RSSI measurements.

In [21], a new cooperative and relative positioning system for UAV ad hoc networks is proposed. This system uses the INS, static UWB nodes, and Wi-Fi access points. It is essentially based on the exchange of information between several static nodes (UWB and access points) and dynamic nodes (drones). In order to obtain an indoor location solution, each drone measures the distances from the static UWB and from neighboring drones; it also measures the strength of the signal received from the Wi-Fi access points, and uses the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) to fuse all of these measurements.

An optimization method is presented in [22] to solve the relative localization problem. Where a real-time 3-D relative position estimator is presented for a UAV swarm system in formation flight, using measurements from the IMU (inertial measurement unit), compass, GPS, and a set of UWB ranging radios. Instead of using stationary UWB anchors to provide 3-D coordinates and fusing it with IMU data, the estimator uses UWB measurements for the construction of a nonconvex function, and calculates the global optimum of the non-convex function to get position estimation, while the GPS positions are used to provide bearing information.

In [23], a swarm-intelligence-based localization (SIL) in UAV networks for emergency communications is proposed. The SIL algorithm is based on particle swarm optimization (PSO), exploiting the particle search space in a limited boundary by using the bounding box method. In the 3-D search space, anchor UAV nodes (equipped with GPS) are randomly distributed; then, the SIL algorithm measures the distance to existing anchor nodes to estimate the location of the target UAV nodes. Therefore, these methods [23, 24] can only be used in open environments where GPS signals are available.

All the techniques proposed for solving the problem of relative localization in UAV ad hoc networks are essentially based on fixed infrastructures, or on sensors embedded in drones [29- 31]. Therefore, they are very expensive [32], slow, consume a lot of power, and require efficient fusion techniques to merge different measures. In the following section, we propose a new relative localization technique that does not require any installed infrastructure, additional devices or dedicated sensors. Instead, it relies solely on the exchange of estimated distances between drones in indoor environments.

3.RLSUAV: RELATIVE LOCALIZATION IN A SWARM OF UAVS

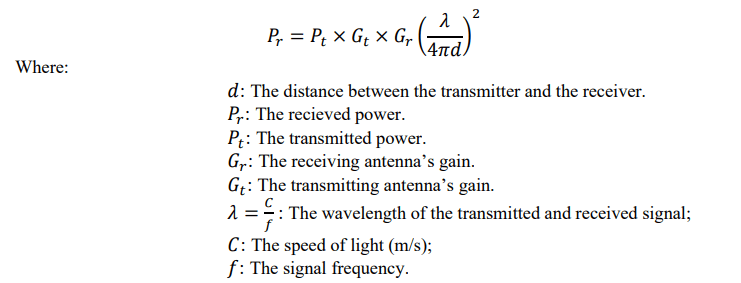

The approach Relative localization in a Swarm of UAVs (RLSUAV) proposed in this paper aims to establish relative positions of all UAVs belonging to a same network in an environment without GPS (for example, a tunnel or mine). It is essentially based on a technique of establishing the relative positions of neighbors nodes which combines the distances measured between UAVs and the multilateration technique. These distances are calculated using the received signal strength technique (RSSI), which is given by the formula of Friis [33]:

Our RLSUAV approach must be executed in three phases: phase of detection of 1-hop and 2-hop neighbors, phase of determining the local positioning system, and the last phase of determining the global positioning system.

3.1. Detection of One- Hop and Two-Hop Neighbors

his step allows the initiator node M (the ground station can play the role of the initiating node M) to detect its 1-hop and 2-hop neighbors, and also allows calculating the distances between the UAVs. To this end, the initiator node M broadcasts a message of type request (REQ) to all its neighbors. Each neighbor node (1-hop), upon receiving this message, broadcasts it to all its neighbors (cf. Figure 1).

Each 2-hop neighbor of the node “M” that receives a message of type REQ responds with a message of type REP. When a 1-hop neighbor of the node “M” receives a message type REP of all its neighbors, it creates a message of type REPN (which contains the list of all its neighbors and the distances between them), and then sends it to the initiator node. At the reception of this message (REPN), the initiator node M can know all its neighbors (1-hop and 2-hop), and the distances between them (cf. Figure 2)

3.2. Determination of the Local Positioning System

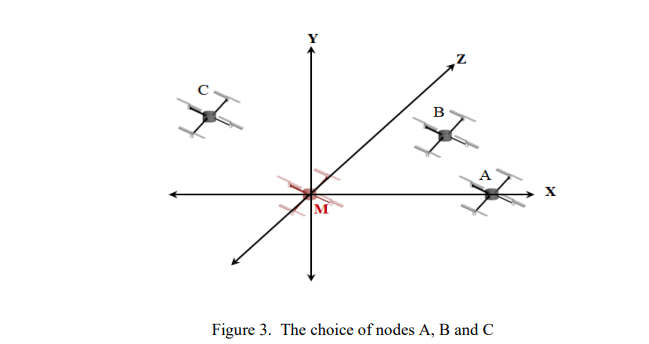

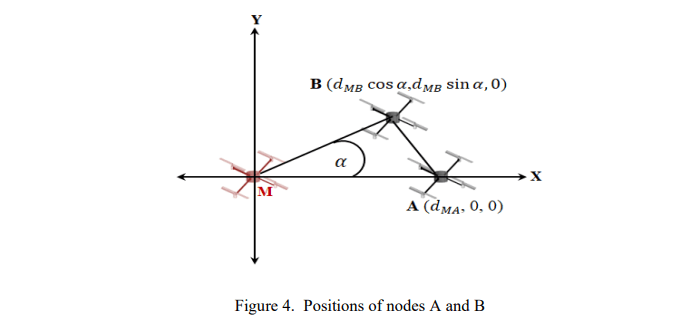

This step allows the initiator node to calculate the positions of its 1-hop neighbors. To accomplish this, the initiator node M will choose three neighbors A, B and C such that (cf. Figure 3):

- Node “A” is on the x-axis (X) and has a positive component Ax

. - Node “B” has a positive component By, and is a common neighbor of “M” and “A”.

- Node “C” has a positive component 𝐶𝑧

, and is a common neighbor of “M”, “A” and “B”. - Nodes M, A, B and C are not coplanar (are not on the same plane)

Node “M” sends a confirmation message to the A, B and C nodes to calculate their positions. Upon reception of this message, the following algorithm is executed:

- When node “C” receives three positions of the nodes “M”, “A” and “B”, it can calculate

its position C(Cx, Cy, Cz) using the trilateration technique (cf. Figure 5) and diffuses it to

all its neighbors.

To calculate the position of node “C”, it suffices to solve the following equation system:

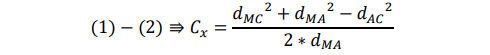

By subtracting the equation (2) from the equation (1), we obtain the value of 𝐶𝑥:

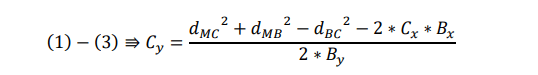

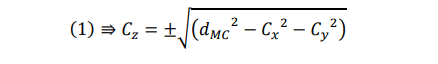

By subtracting the equation (3) from the equation (1), we obtain the value of 𝐶𝑦:

And by replacing 𝐶𝑥 and 𝐶𝑦 in equation (1), we obtain the value of 𝐶𝑧

Since we have already supposed that node C has a positive 𝐶𝑧 component, its value can be

determined as:

3.3. Determination of the Global Positioning System

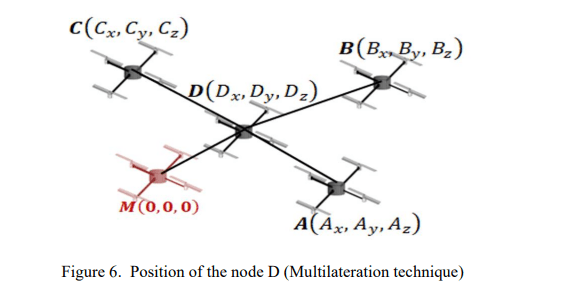

After determining the local positioning system, each neighbor of the nodes “M”, “A”, “B and “C (for example, node D) must calculate its position using the positions of the latter, and considering the distance that separates it from them, by applying the multilateration technique (cf. Figure 6). So, it suffices to solve the following system of equations:

Periodically, the nodes M, A, B, C and D update their positions and they broadcast them to all their neighbors. A node receiving messages from its neighbors can therefore calculate its position (𝒙, 𝒚, 𝒛) if, and only if, it receives four positions from different nodes (cf. Figure 6). However, it can only calculate the components 𝒙 and 𝒚 if it receives three positions (cf. Figure 5).

4.SIMULATION RESULTS

To implement RLSUAV, we chose to use the Cooja simulator within Instant Contiki 2.7. Then, we evaluated the performance of RLSUAV in different environments and by varying several parameters such as the number of messages received, the localization error, and the success rate (localizing percentage of the UAVs). In our simulations, and for each parameter, we used two different radio propagation models. The first one is the UDGM Unit Disk Graph Medium radio propagation model, where the transmission range is an ideal disk; therefore, the UAVs outside the disk do not receive any packets, while the UAVs in that disk receive all the packets.

In order to study the performance RLSUAV using a realistic radio propagation model, we choose the Multi-Path Ray-tracer Medium (MRM) radio propagation model that includes many obstacles, where the received power is calculated using Friis Formula but obstacles (modelled simply as rectangles) are considered as attenuators in the environment [34]. Table 1 summarizes the main simulation parameters used: