IJNSA 05

Static Testing Tools Architecture in OpenMP for Exascale Systems

Samah Alajmani

Department of Computers and Information Technology, Taif University, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

In the coming years, exascale systems are expected to be deployed at scale, offering unprecedented computational capabilities. These systems will address many significant challenges related to parallel programming and developer productivity, distinguishing themselves through massive performance and scalability. Considerable research efforts have been dedicated to this field, with a central focus on enhancing system performance. However, the inherent parallelism and complexity of exascale systems introduce new challenges, particularly in programming correctness and efficiency. Modern architectures often employ multicore processors to achieve high performance, increasing the need for robust development tools. In this paper, we present the design of a static testing tool architecture in OpenMP tailored for exascale systems. The primary objective of this architecture is to detect and resolve static errors that may occur during code development. Such errors can affect both program correctness and execution performance. Our proposed architecture aims to assist developers in writing correct and efficient OpenMP code, thereby improving overall software reliability in exascale computing environments.

Keywords

Exascale Systems, Software Testing, OpenMP, Static Testing Toolsand Programming Models

1. INTRODUCTION

Current trends and research are increasingly focused on exascale systems and high-performance computing (HPC). The next generation of computing will be characterized by extensive parallel processing. Rather than enhancing performance through single-threaded execution, recent advancements in microprocessor design prioritize increasing the number of cores [1]. According to [2], the structural configuration of exascale systems plays a critical role in determining the nature of programming models being developed to simplify the creation of applications at the exascale level.

Moreover, the development of HPC systems demands programming models capable of detecting and resolving errors. In this context, OpenMP has emerged as one of the most widely adopted standards for shared-memory parallel programming in HPC. Despite its advantages in simplifying parallel application development, OpenMP programs remain susceptible to both general parallel programming errors and errors specific to the OpenMP model.Resilience is also a key requirement in exascale supercomputers. Parallel programs must be able to detect and respond to faults or events that could otherwise lead to program failure or incorrect results [3].

The structure of this paper is as follows: The first section introduces exascale systems and the OpenMP programming model. The second section categorizes common static errors in OpenMP programs. The third section reviews related work on static analysis tools for OpenMP. The fourth section presents the proposed static testing tool architecture for OpenMP in exascale systems, including its structural configuration. This is followed by an evaluation of the proposed architecture. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary and suggestions for future work.

1.1. Exascale System

The term exascale refers not only to advanced, floating-point-intensive supercomputers capable of achieving exaflop-level performance but also emphasizes improving computational efficiency across a wide range of traditional and emerging applications [4]. Exascale computing systems are defined as those capable of executing approximately 10¹⁸ operations per second [5].

1.2. OpenMP Programming

The primary focus of OpenMP has been to provide a portable parallel programming model for high-performance computing (HPC) platforms [6]. OpenMP, which stands for Open Multi- Processing, is a programming model designed to support multithreading through shared-memory parallelism in computing systems [7]. Its main objective is to simplify the development of parallel applications [8]. However, OpenMP has limitations in terms of error detection and prevention, which can hinder its widespread adoption by industry [6]. Therefore, there is a need for robust implementations in OpenMP that offer best-effort mechanisms to detect both static and runtime errors.

2. Static Errors

It is important to note that the development of OpenMP programs is prone to concurrency-related errors, such as deadlocks and data races. OpenMP programs can exhibit various types of errors – some of which have already been identified, while others remain to be discovered [9]. Researchers generally classify these errors into two main categories: correctness errors and performance errors.Correctness errors affect the program’s intended behaviour – for example, accessing shared variables without proper synchronization. In contrast, performance errors degrade the efficiency of the program, such as performing excessive work within a critical section, which can lead to performance bottlenecks [10].Other studies have shown that detecting complex correctness issues, such as data races or verifying OpenMP’s target directives, requires detailed memory access information, often obtained through binary instrumentation [11]. Various types of static errors in OpenMP will be discussed in the following subsections.

2.1. Forgotten Parallel Keyword

OpenMP directives have a complex syntax, which makes them prone to various types of errors. Some of these errors may be relatively simple but occur due to incorrect directive formatting [12].

Example incorrect code

int main ()

{

#pragma omp

// your code

}

Example correct code

int main ()

{

#pragma omp parallel for

// your code

}

int main ()

{

#pragma omp parallel for

{

#pragma omp for

// your code

}

}

Initially, the code may compile successfully; however, the compiler might ignore the “#pragma omp parallel” for directive. As a result, the loop will be executed by a single thread, which may not be easily detected by the developer. In addition, errors can occur when using the “#pragma omp parallel” directive, particularly in combination with the sections directive.

2.2. Using Ordered Clause without Need to Ordered Construct

An error can occur when an ordered clause is specified in a for-work-sharing construct without including a corresponding ordered directive inside the enclosed loop. In such cases, the loop is expected to execute in order, but the absence of the internal ordered directive leads to incorrect behaviour [8].

Example incorrect code

#pragma omp parallel for ordered for ( i = 0 ; i< 20; i++ )

{ myFun(i); }

Example correct code

#pragma omp parallel for ordered for ( i = 0 ; i< 20; i++ )

{ #pragma omp ordered

{ myFun(i); }

}

2.3. Unnecessary Directive of Flush

In some cases, the compiler may implicitly insert flush constructs at specific points in the code. Manually adding a flush directive before or after these points can lead to performance degradation [8]. This is especially problematic when flush is used without parameters, as it forces synchronization of all shared variables, which can significantly slow down program execution. The following list highlights the situations where an implicit flush is already applied, and therefore, it is unnecessary to add an explicit flush:

- At a barrier directive

- On entry to and exit from a critical region

- On entry to and exit from an ordered region

- On entry to and exit from a parallel region

- On exit from a for construct

- On exit from a single construct

- On entry to and exit from a parallel for construct

- On entry to and exit from a parallel sectionsconstruct [12].

Example incorrect code

#pragma omp parallel for num threads(2) for ( i = 0 ; i< N; i++ )

myFun();

#pragma omp flush()

Examples correct code

#pragma omp parallel for num threads(2) for ( i = 0 ; i< N; i++ )

myFun();

2.4. Forgotten Flush Directive

According to the OpenMP specifications, the flush directive is implicitly included in several cases. However, developers may sometimes forget to place the directive where it is explicitly required. The flush directive is not automatically included in the following situations:

- On entry to a for construct

- On entry to or exit from a master region

- On entry to a sections construct

- On entry to a single construct [8], [12].

Example incorrect code

int a = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for num threads(2)

{ a++;

#pragma ompsingle;

{ cout<< a <<endl;}

}

Example incorrect code

correct int a = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for num threads(2)

{ a++;

#pragma ompsingle;

{ #pragma omp flush(a) cout<< a <<endl;}

}

2.5. Race Condition: Sex Sections

Sometimes, if memory access does not occur within one of the following six sections—critical, master, reduction, atomic, lock, or single – it can lead to a race condition [13].

2.6. Race Condition: Shared Variables

A race condition occurs when two or more threads access a shared variable simultaneously, and at least one of these accesses involves a write operation. This happens because there is no proper synchronization mechanism in place to prevent concurrent access [9], [13]. In other words, the access to shared memory is unprotected. To avoid such issues, an atomic section can be used to ensure safe and synchronized access to shared variables [14].

Example incorrect code

int m = 0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

m++;

}

Example correct code

Int m = 0;

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp atomic m++;

}

2.6. Many Entries inside Critical Section

This issue can be divided into two parts:

First, enclosing more code within a critical section than necessary can cause other threads to be blocked longer than needed. The best solution is for the programmer to carefully review the code to ensure that only the essential lines are inside the critical region. For example, calls to complex functions often do not need to be inside the critical section and should be executed beforehand, if possible [7], [8], [14].

Second, maintenance costs can become very high if threads frequently enter and exit critical sections unnecessarily. Excessive entries and exits to critical sections degrade performance. To reduce this overhead, it is advisable to move conditional statements outside the critical region. For instance, if a critical section is guarded by a conditional statement, placing this condition before the critical region can prevent unnecessary entries during loop iterations [7], [8], [14].

Example incorrect code

#pragma ompparallel for for ( i = 0 ; i< N; ++i )

{

#pragma omp c r i t i c a l

{ i f ( a r r [ i ] > max) max = a r r [ i ] ; }

}

Example correct code

#pragma ompparallel for for ( i = 0 ; i< N; ++i ) {

#pragma omp f lush (max) i f ( a r r [ i ] > max) {

#pragma omp c r i t i c a l

{

i f ( a r r [ i ] > max) max = a r r [ i] ;

}

}

}

2.7. Forgotten for in“ #pragma omp parallel for”

This type of error is very common in OpenMP. Although many developers use the for clause to specify that a loop should be parallelized within a #pragma directive, they often forget to include the for clause itself. This mistake can cause each thread to execute the entire loop instead of just a portion of it.An important point to note is that even if for clause is present in the directive, but the loop is not correctly placed within the parallel region, the program may still produce errors [7].

Example

#pragma omp parallel for

{

if ( arr [ 0 ] > v1)

{

if ( arr [ 1 ] > v2) max = arr [ 2 ] ;

}

}

3. Related Work

Various techniques are employed in software testing, including dynamic and static analysis methods [15]. Dynamic analysis involves monitoring program execution, but it is limited to a finite set of inputs. The trace-based approach stores events independently of the program in a trace file, allowing analysis from the program’s start to its completion. Some dynamic tools, such as Intel Thread Checker and Sun Thread, can detect data races and deadlocks [10].

Static analysis, on the other hand, examines a program without executing it. It can identify faulty program functions and generate warnings for potential errors. Static analysis can explore all possible program execution paths and is often capable of detecting synchronization issues (e.g., race conditions and deadlocks) as well as data usage errors, such as incorrect handling of shared variables in concurrent processes [10].

Many static analysis tools are available for OpenMP programming. Since this study focuses on static analysis, this section is divided into three parts: the first and second parts present two well- known static analysis tools, Parallel Lint and VivaMP. The final part reviews additional tools commonly used in related work.

3.1. Parallel lint

In parallel programming, Parallel Lint assists programmers in writing and debugging code. It also supports the development of parallel applications and the parallelization of existing serial applications. Parallel Lint performs static interprocedural analysis to identify parallelization errors in OpenMP programs. Moreover, it can detect errors that are not caught by compilers. OpenMP offers a variety of ways to express parallelism, and Parallel Lint is capable of detecting issues related to OpenMP clauses and directives, variables in parallel regions (e.g., reduction, private, shared), the dynamic extent of parallel sections, nested parallel sections, thread-private variables, and expressions used within OpenMP clauses. Despite these strengths, Parallel Lint has limitations, such as inadequate handling of critical sections in OpenMP programs [16].

3.2. Vivamp

VivaMP is a powerful specialized tool designed primarily for verifying application code built using OpenMP technology [17]. It also assists developers in creating OpenMP-based parallel software [18]. VivaMP is a C/C++ code analyzer aimed at detecting errors in existing OpenMP programs and simplifying the development process for new ones. If errors occur in a parallel program that the compiler fails to detect, VivaMP can identify these errors, allowing developers to easily correct them. VivaMP can detect both legacy errors in existing OpenMP solutions and errors in newly developed OpenMP code [18]. Additionally, its analyzers can be integrated into Visual Studio 2005/2008, enabling users to start working immediately without complex setup or the need to reorder comments in the program code. This ease of use is one of the tool’s main advantages. However, like other static analyzers, VivaMP requires further configuration during use to reduce false positive results, which is an inherent trade-off for the demands of static analysis tools [17]. Finally, this tool also has limitations in handling multiple entries within critical sections.

3.3. Different Analysis Tools

This section introduces related works regarding different testing tools, part of which are employed for different program models such as OpenMP, IMP, and CUDA, and another part of which offers static analysis tools for OpenMP programming.

Firstly, in recent studies introduced by Salwa et al. [19], it was proposed that a novel testing tool that makes use of linear temporal logic (LTL) features to identify runtime errors in hybrid OpenMP and MPI applications.Their tool efficiently detects race conditions and deadlocks, improving system reliability by concentrating on runtime errors resulting from hybrid OpenMP and MPI.

Saeed et al. [20] proposed that the static analysis tool, which was designed especially for tri- model applications MPI,OpenMP and CUDA. This tool analyzed C++ source code to detect both actual and possible runtime errors before implementation. By providing both comprehensive static detection and classification of error, the suggested tool decreases the need for manual testing while improving error visibility. So, this makes a significant contribution to the improvement of more resilient parallel applications for future exascale systems and HBC.

Salwa et al. [21] proposed the testing tool based on a temporal logic using techniques of instrumentation, which is designed for MPI and OpenMP with a C++ environment. After an extensive study of types of temporal logic, they demonstrated that their tool of linear temporal logic was very suitable as the foundation for their tool.

Secondly, this part presents related works regarding different static analysis tools for programming models. Basupall et al. [22] stated that access control lists (ACLs) are automatically extracted from an input C program by OmpVerify, which then flags errors with detailed messages for the user. They demonstrated the effectiveness of their technique on several straightforward yet challenging cases involving subtle parallelization issues that are difficult to detect, even for experienced OpenMP programmers.

Chatarasi et al. [23] extended the polyhedral model to analyze parallel SPMD programs and proposed a novel method utilizing this extended polyhedral model. They evaluated their approach on thirty-four OpenMP programs from PolyBench-ACC and OmpSCR (PolyBench-ACC is derived from the PolyBench benchmark suite and provides implementations in OpenMP, OpenCL, OpenACC, CUDA, and HMPP).

Ye et al. [24] presented a polyhedral analysis approach to verify the absence of data races. Their analysis showed high precision, reporting no false positives for affine loops analyzed in AMG2013 and DataRaceBench.

Swain et al. [25] introduced OMPRACER, a purely static analysis tool for detecting data races in OpenMP programs. OMPRACER supports most commonly used OpenMP features and, unlike dynamic tools, can identify logical data races regardless of input or hardware configuration. Their evaluation on real-world applications and DataRaceBench showed that static analysis can compete with—and sometimes outperform—state-of-the-art dynamic OpenMP race detection tools. OMPRACER detected both known races, such as those in CovdSim, and previously unknown races in miniAMR.

Bora et al. [26] proposed LLOV, a lightweight, fast, language-independent data race checker for OpenMP programs built on the LLVM compiler framework. They evaluated LLOV against other race checkers using a range of well-known benchmarks. The results showed that LLOV’s precision, accuracy, and F1 score are comparable to other tools, while operating significantly faster. To their knowledge, LLOV is the only advanced data race checker capable of formally verifying that a C/C++ or FORTRAN program is free of data races.

4. Proposed Architecture

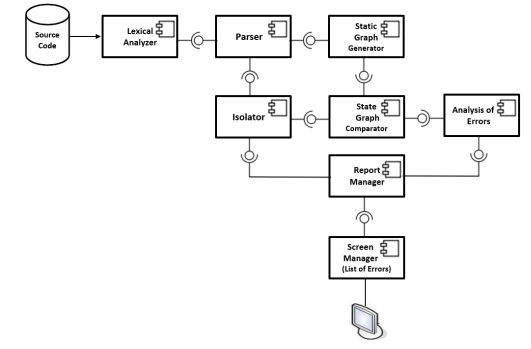

This architecture has been proposed to detect static errors that have not been identified by other tools, such as VivaMP and Parallel Lint. It follows a specific process to detect static errors and generates a report listing these errors. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed architecture of the static testing tool for OpenMP.

Figure 1. Architecture of Component Based Static Testing Tool in OpenMP

The following steps explain the components and workflow of this architecture:

Lexical Analyzer Component:

This component breaks the OpenMP source code into tokens, producing a tokens file. It analyzes the input string, removes unnecessary whitespace, and converts the code into a sequence of meaningful characters such as operators, keywords, and identifiers according to OpenMP grammar. This phase does not involve syntax checking but prepares the code for subsequent stages by simplifying processing.

Parser Component:

The parser checks whether the syntax of the code is correct. Once parsing is complete, it forwards the code to the semantic analysis component. After analysis and parsing, two copies of the processed code are generated: one for the static graph generator and another for the isolator component.

Semantic Analysis Component:

This component ensures that the code statements are clear and logically understandable. It also creates two copies of the analyzed code: one for the static graph generator and another for the isolator.

Static Graph Generator Component:

This component generates a state graph from the tokens file representing the user’s OpenMP code.

State Graph Comparator Component:

This component compares the state graph of the user’s OpenMP code with the original programming language’s state graph to identify static errors. If errors are found, it passes them to the error analysis component.

Analysis of Errors Component:

This component analyzes the detected errors in detail to precisely locate them, which facilitates later correction. It then sends this information to the report manager.

Isolator Component:

This component works alongside the analysis module to detect issues such as race conditions and multiple entries inside critical sections. It forwards this information to the report manager, which coordinates error handling.

The testing tool examines the OpenMP source code from two perspectives:

- Race conditions

- Multiple entries inside critical section

4.1. Race Condition

The first step checks all accesses to determine if they occur within any of the following six sections: critical section, master section, reduction section, atomic section, lock section, or single section. If the access is within any of these sections, the report manager is informed that a race condition exists; otherwise, no race condition is reported.

The second step examines shared variables. If two or more threads access the same shared variable and at least one of these accesses is a write, this leads to a race condition. In this case, the report manager is notified to prevent the error or to generate a report detailing the error. Otherwise, the code is considered correct with no race condition present.

4.2. Many Entries inside the Critical Section

Firstly, it checks all statements in the code. If there are any statements or complex functions that do not need to be inside the critical section, the programmer should move them before the critical section.

Secondly, it checks the number of entries and exits to the critical section. For example, if a conditional statement can be executed before entering the critical section, the report manager is informed so that this statement can be moved and executed prior to the critical section.

Report Manager Component:

This component interacts with both the isolator and error analysis components. It receives information about errors, is passed to the report manager to manage the process of error handling. Also, it attempts to help fix them and generates a list of detected static errors.

Screen Manager Component:

This component represents the final stage and interfaces with the display. Its main role is only to present the list of static errors identified during earlier stages.

5. Evaluation of the Architecture

As we know, system performance is critically important, especially in exascale systems. Therefore, we propose this architecture—a static testing tool for OpenMP in exascale systems— with the primary objective of significantly improving their performance.

It is important to note that although exascale systems run millions of threads, they require reliability and high-speed during execution. Achieving this assumes that the code is written correctly and free of errors, but often the opposite occurs. Due to the large size of these programs, they can require extensive time to execute. This tool, built on OpenMP technology, aims to detect a number of static errors early in the development process and resolve them as much as possible. Overall, this approach can reduce the number of errors and enhance performance, thereby ensuring the correctness, reliability, and high efficiency of exascale systems.

6. Conclusion

Nowadays, much research focuses on designing appropriate architectures that contribute to the development of exascale systems in terms of techniques, languages, and algorithms. In this context, this paper proposes an architecture for a static testing tool in OpenMP tailored for exascale computing systems. The primary goal of this tool is to improve the performance of high- performance computing (HPC) systems.We have presented various static errors in OpenMP that may occur during coding but remain undetected by the compiler. Furthermore, we have designed an architecture to detect these errors, generate a list of static errors, and provide ways to prevent them. Among the most critical issues addressed are race conditions and excessive work inside critical regions. Additionally, there are other errors in OpenMP that remain undetected so far.This architecture aims to help developers and programmers identify the location of errors in OpenMP code and prevent them. For future work, we recommend continuing and strengthening research efforts to detect and prevent errors in OpenMP. We also encourage implementing this architecture and conducting extensive experiments to evaluate its performance and effectiveness in testing OpenMP code.

REFERENCES

[1] J. D. Owens, M. Houston, D. Luebke, S. Green, J. E. Stone, and J. C. Phillips, “GPU Computing,” Proc. IEEE, Vol 96, pp. 879–899, 2008.

[2] J. Dongarra et al., “The International Exascale Software Project roadmap,” Int. J. High Perform. Comput. Appl.,Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 3–60, 2011.

[3] J. F. Münchhalfen, T. Hilbrich, J. Protze, C. Terboven, and M. S. Müller, “Classification of common errors in OpenMP applications,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics),Vol. 8766, pp. 58–72, 2014.

[4] P. Kogge et al., “ExaScale Computing Study : Technology Challenges in Achieving Exascale Systems,” Gov. Procure., Vol. TR-2008-13, p. 278, 2008.

[5] P. Kruchten, “What do software architects really do?,” J. Syst. Softw.,Vol. 81, No. 12, pp. 2413– 2416, 2008.

[6] M. Wong et al., “Towards an error model for OpenMP,” Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics), Vol. 6132 LNCS, pp. 70–82, 2010.

[7] M. U. Ashraf, “Hybrid Model Based Testing Tool Architecture for Exascale Computing System,” No. 9, pp. 245–252.

[8] M. Süß and C. Leopold, “Common Mistakes in OpenMP and How to Avoid Them: A Collection of Best Practices,” Proc. 2005 2006 Int. Conf. OpenMP Shar. Mem. Parallel Program., pp. 312–323, 2008.

[9] H. Ma, S. R. Diersen, L. Wang, C. Liao, D. Quinlan, and Z. Yang, “Symbolic analysis of concurrency errors in OpenMP programs,” Proc. Int. Conf. Parallel Process., pp. 510–516, 2013.

[10] M. H. P. C. Applications, “Analyse statique / dynamique pour la validation et l ’ amélioration des applications parallèles,” 2015.

[11] J. Treibig, G. Hager, and G. Wellein, “Tools for High Performance Computing 2011,” pp. 27–36, 2012.

[12] A. Karpov, “32 OpenMP traps for C++ developers | Intel® Software,” 2015. [Online]. Available: https://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/32-openmp-traps-for-c-developers. [Accessed: 7-May- 2025].

[13] H. Ma, Q. Chen, L. Wang, C. Liao, and D. Quinlan, “An OpenMP analyzer for detecting concurrency errors,” Proc. Int. Conf. Parallel Process. Work., pp. 590–591, 2012.

[14] A. Kolosov, A. Karpov and E. Ryzhkov “VivaMP, system of detecting errors in the code of parallel C++ programs using OpenMP,” 2009.

[Online]. Available:https://www.viva64.com/en/a/0059/#ID0ELTBI. [Accessed: 30-April-2025].

[15] A. M. Alghamdi and F. E. Eassa, ‘‘Software testing techniques for parallel systems: Asurvey,’’ Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur.,Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 176–186, 2019.

[16] D. Shah, “Analysis of an OpenMP Program for Race Detection,” Test, 2009.

[17] A. Karpov, “Parallel Lint,” 2011. [Online]. Available: https://software.intel.com/en- us/articles/parallel-lint. [Accessed: 7-May-2025].

[18] E. Ryzhkov, “VivaMP – a tool for OpenMP,” 2009. [Online]. Available: https://pvs- studio.com/en/blog/posts/a0058/#ID015DAFC352. [Accessed: 30-April-2017].

[19] Saad, S., Fadel, E., Alzamzami, O., Eassa, F., & Alghamdi, A. M. (2025). “Temporal-Logic-Based Testing Tool for Programs Using the Message Passing Interface (MPI) and Open Multi-Processing (OpenMP) Programming Models”. IEEE Access.

[20] Altalhi, S. M., Eassa, F. E., Sharaf, S. A., Alghamdi, A. M., Almarhabi, K. A., & Khalid, R. A. B. (2025). “ Error Classification and Static Detection Methods in Tri-Programming Models: MPI, OpenMP, and CUDA”. Computers, 14(5), 164.

[21] Saad, S., Fadel, E., Alzamzami, O., Eassa, F., & Alghamdi, A. M. (2024). “Temporal-Logic-Based Testing Tool Architecture for Dual-Programming Model Systems”. Computers, 13(4), 86.

[22] V. Basupalli, T. Yuki, S. Rajopadhye, A. Morvan, S. Derrien, P. Quinton, and D.Wonnacott,‘‘OmpVerify: Polyhedral analysis for the OpenMP programmer,’’ in Proc. 7th Int. Workshop OpenMP Petascale Era, 2011, pp. 37–53, doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-21487-5_4.

[23] P. Chatarasi, J. Shirako, M. Kong, and V. Sarkar, ‘‘An extended polyhedral model for SPMD programs and its use in static data race detection,’’in Proc. 29th Int. Workshop Lang. Compil. Parallel Comput., 2017,pp. 106–120, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-52709-3_10.

[24] F. Ye, M. Schordan, C. Liao, P.-H. Lin, I. Karlin, and V. Sarkar, ‘‘Using polyhedral analysis to verify OpenMP applications are data race free,’’ in Proc. IEEE/ACM 2nd Int. Workshop Softw. Correctness HPC Appl. (Correctness), Nov. 2018, pp. 42–50, doi: 10.1109/CORRECTNESS.2018.00010.

[25] B. Swain, Y. Li, P. Liu, I. Laguna, G. Georgakoudis, and J. Huang,‘‘OMPRacer: A scalable and precise static race detector for OpenMP programs,’’ in Proc. Int. Conf. High Perform. Comput., Netw., Storage Anal., Nov. 2020, pp. 1–14, doi:10.1109/SC41405.2020.00058.

[26] U. Bora, S. Das, P. Kukreja, S. Joshi, R. Upadrasta, and S. Rajopadhye, ‘‘LLOV: A fast staticdata- race checker for OpenMP programs,’’ ACM Trans. Archit. Code Optim., Vol.17, No. 4, pp. 1–26, Dec. 2020, doi:10.1145/3418597.