IJNSA 03

ANALYSING THE IMPACT OF PASSWORD LENGTH AND COMPLEXITY ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF BRUTE FORCE ATTACKS

Lama A. AlMalki 1, Samah H. Alajmani 1, Ben Soh 2and Raneem Y. Alyami 1

1 Department of Computers and Information Technology, Taif University,Taif City, KSA

2 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology,La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia

ABSTRACT

This study investigates the critical role of password length and complexity in mitigating the effectiveness of brute force attacks, a prevalent method used by attackers to gain unauthorized access to systems. Passwords are the first line of defense in digital security, and their strength directly affects the time and resources required for a brute-force attack to be successful. The research explores the relationship between various password characteristics such as length, the inclusion of alphanumeric characters, special

symbols, and case sensitivity and the resistance they provide against automated cracking attempts. Through a combination of theoretical analysis and practical simulation, the study demonstrates how even a small increase in password length can lead to exponential growth in the number of possible combinations, significantly delaying potential breaches.

KEYWORDS

Password security, brute force attacks, password length, password complexity, cybersecurity

1. INTRODUCTION

In our digital age, passwords play a crucial role in cybersecurity, safeguarding sensitive information, personal accounts, and organizational systems. However, as cyber threats continue to evolve, conventional password strategies are coming under greater scrutiny due to their susceptibility to brute force attacks. These attacks involve systematically guessing password combinations, with the likelihood of success largely dependent on the length and complexity of the password. The length of a password plays a crucial role in determining the total number of possible combinations. In addition, incorporating complexity—such as a mix of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and special symbols—greatly improves its resistance to automated cracking attempts. This study examines how these factors influence the effectiveness of brute force attacks to offer recommendations for creating stronger and more practical password policies. The main aim of this study is to analyze the impact of password length and complexity on the effectiveness of brute force attacks and provide recommendations for creating secure,

practical password policies that provide security. This includes evaluating the relationship between password length and the time required to crack it using brute force attacks, as well as examining how password complexity, including the use of alphanumeric characters, symbols, and case sensitivity, affects resistance to brute force attacks. Passwords serve as a fundamental layer of security for digital systems, yet they remain highly susceptible to exploitation. Brute force attacks, which involve systematically guessing password combinations, have become increasingly

effective due to advancements in computational capabilities. A major factor contributing to this vulnerability is users’ widespread use of weak passwords, such as short, simple, or commonly reused passwords, making accounts more susceptible to compromise. This study investigates how password characteristics, particularly length and complexity, impact the effectiveness of brute

force attacks.

Due to the increasing information sharing, popularity of the Internet, e-commerce transactions, and data transfer, password security has become an essential issue.

In 1979, Morris and Thompson first identified text passwords as a weakness in information systems security. They discovered that a large percentage of weak passwords, 89%, were because they were too short or contained only numbers or only lowercase letters and, therefore, could be easily found in dictionaries. Since the inception of passwords, we have witnessed significant transformations in digital identity and authentication. However, regrettably, some aspects have remained unchanged [1].

Password security has evolved significantly over time, driven by the increasing sophistication of cyber-attacks and technological advances. Passwords were introduced as a direct way to control access to computer systems in the 1960s and 1970s [2]. These early passwords were short and simple, as the computational power needed to break them was minimal. However, as technology advanced, attackers began using brute force techniques to exploit weak passwords, revealing vulnerabilities in these systems [3].

In the early 2000s, the rapid growth of the Internet and a rise in data breaches underscored the urgent need for stronger password security. In response, organizations began to adopt password policies that mandated the use of combinations of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols. Additionally, they required users to update their passwords every three to six months. [1]. Despite these policies, many users prioritized convenience over security and continued to use very weak, easy-to-remember passwords that were also highly vulnerable to attacks [4].

Research in recent years has confirmed that short, simple passwords are insufficient against modern cyber threats and attacks. Reports from the National Institute of Standards and Technology NIST and Google Security have shown that passwords that are most resistant to brute force attacks are those that contain different types of characters and are longer than 12 characters. This shift reflects the increasing focus on creating secure and easy-to-use mechanisms, such as password managers and multi-factor authentication, to address the limitations of traditional password systems. These days, the main challenge is that there are still users who are reluctant to adopt stronger password practices due to the perceived inconvenience and difficulty [5].

As years passed, researchers have explored many different ways to strengthen password security by increasing password length and requiring password complexity. Thus, a longer and more complex password is generally more secure, but it also faces challenges in terms of brute force

attacks.

Brute force attacks are a common technique in cybersecurity used across various fields to break encrypted messages and passwords by systematically attempting all possible combinations until the correct one is found [6]. This method operates under the assumption that the encryption algorithm is known, but the key or password remains unknown [7].

Brute force attacks, which involve repeatedly attempting to guess credentials or encryption keys, have emerged as a major concern in the realm of cybersecurity. In 2018, these attacks represented 18% of all cyber incidents managed by the security incident response team at F5 Networks.

Certain sectors have been more heavily targeted than others. For instance, within the public sector, a staggering 50% of cyber incidents were attributed to brute force attacks, followed closely by the financial services sector at 47. 8%, and healthcare at 41. 7%. These figures underscore the urgent need for robust security measures across various industries to effectively address the rise of brute force attacks [8].

In the Middle East, the threat landscape has shifted significantly with the increasing number of Internet of Things (IoT) devices. In 2022, Kaspersky’s honeypots identified and thwarted 337,474 attacks aimed at IoT devices in the region. Notably, over 113,000 of these attempted breaches utilized brute force methods to gain access to device credentials. This highlights the critical need for securing IoT devices through the use of strong, unique passwords and routine firmware updates to reduce the risk of such threats[9]. To start the attack, the attacker needs to follow several steps:

The first step is for the attacker to choose the target account, such as an email or a website account.

The second step is to collect information. The attacker can analyse the password policies of the target site, such as the number of characters, the requirements for symbols and numbers, and the number of attempts to log in to the account.

The third step is to choose the tools, prepare them, and use the programs. Here, the attacker chooses and uses programs dedicated to cracking passwords. These programs include:

* Hashcat: One of its features is that it supports more than 250 Hashing Algorithms and also

relies on GPU acceleration, which makes it faster than tools that rely on GPU.

* John the Ripper: An open source, free tool specialized in testing the strength of passwords

and cracking them. One of its notable features is the Wordlist Attack mode, which utilizes

previously leaked passwords to expedite the cracking process.

* Hydra: A very powerful tool, unlike Hashcat and John the Ripper, it targets services across

the network rather than stored hashes and tests the strength of passwords in remote login

protocols [10].

Finally, the attack is executed. When the correct password for the account is found, the attacker can gain unauthorized access to the account and then carry out other attacks. [11]. The time required to crack passwords by brute force can be calculated and determined by the number of possible combinations and is calculated as follows:

Total Combinations = Character Set Size^ Password Length

For Example, a password containing only 4 lowercase letters (26 characters) has 26^4 = 456.976 possible combinations. Another example of lowercase letters, a password containing only 8 lowercase letters (26 characters) has 26 ^ 8 = 208.827.064.576 possible combinations.

Here, it is clear that when using a short number of characters, the attacker does not get tired of cracking passwords. But let us explain the difficulty when using uppercase and lowercase letters, symbols, and numbers ( ~ 95 characters ). It has 95^8 =6.63*10^15 possible combinations, which makes it exponentially harder to crack.

In this section, we will explore some fundamental concepts associated with passwords. A password serves as a means of confirming a user’s access to a specific system. It is typically composed of a blend of letters, numbers, and symbols, enabling users to unlock computers,applications, or other systems [12]. Passwords are essential in safeguarding against unauthorized access to computers, networks, and a variety of technologies. A weak password is easy to guess or hack. Examples of weak passwords include simple combinations such as “123456,” “password,” birthdays, phone numbers, and personal information like names and surnames. These passwords are highly vulnerable to attacks and can be easily compromised in a short amount of time [13].

In contrast, a strong password is difficult to guess or hack but may also be harder to remember due to its complexity. Strong passwords always contain a random and diverse combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols, and they are typically at least 16 characters long. There is a direct relationship between password length and complexity – the longer and more complex a password, the stronger it is considered. The strength of a password is influenced by its length, specifically the number of characters it includes. Longer passwords are more secure because they significantly increase the number of possible combinations. For instance, a 6-character password composed solely of lowercase letters has approximately 26^6 (or 26 to the power of 6) possible combinations. In contrast, a 16-character password that incorporates a blend of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols offers an exponentially greater number of combinations. This significant increase in complexity makes it

much more resistant to attacks [14].

Various types of attacks can target passwords, rendering them susceptible to easy compromise.One of the most prevalent forms of attack is the brute force method. In this approach, an attacker systematically tries to guess login credentials, encryption keys, or even concealed web pages by employing a trial-and-error strategy. The attacker systematically tests every possible combination until the correct one is discovered. This method relies entirely on repeated and persistent attempts to break into accounts or systems. Despite being an old technique, it remains widely used and effective. The time it takes to crack a password varies significantly based on its length and complexity. Weak passwords may be compromised in just a matter of seconds, while stronger ones could take years to crack [6].

The basic concepts of password length and complexity analysis, as well as how a brute force attack occurs, are covered. The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Previous literature is reviewed in the second section. The third section explains the practical aspects of password analysis and strength measurement. It combines two algorithms, Zxcvbn and Random Forest Classifier, to achieve highly accurate results and analyzes the outcomes using the Plotly library. We conclude the paper with the fourth and fifth sections, which discuss future work and the conclusion, respectively.

2. RELATED WORK

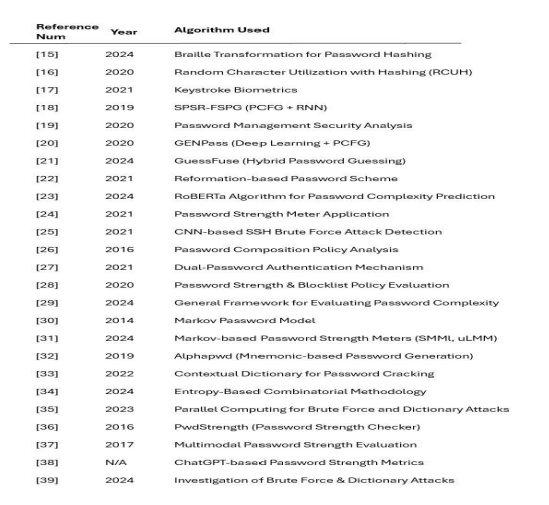

The following 25 reviews examine existing research on the impact of password length and complexity on the effectiveness of brute force attacks. It explores how these factors influence password strength and the computational feasibility of brute force attacks.

Hamza et al. [15] sought to create a groundbreaking approach to strengthening password security prior to their storage in databases. It presents a unique method that utilizes Braille transformation to encrypt password hashes, adding an extra layer of protection against unauthorized access. The findings demonstrate a notable enhancement in both password complexity and overall security. This research underscores the critical necessity for innovative security solutions to address the escalating sophistication of cyber threats, their approach mainly focuses on storage security, whereas our research investigates both storage and resistance to brute-force attacks. This

highlights a gap in the literature that our study aims to address by examining the interplay between password length, complexity, and cracking time.

Kumar and Reddy [16] introduced the RCUH model to enhance password security through targeted generation protocols. Their study assesses cracking time but focuses more on password creation than real-world attack scenarios. Unlike their work, our research evaluates the impact of password length and complexity on cracking resistance across multiple hashing algorithms, addressing gaps in practical security analysis.

Simon et al. [17] investigated the relationship between password policies and keystroke biometrics by analyzing 40 dictionary-based passwords of different lengths. Their findings revealed that shorter passwords without substitutions achieved an impressive 94% authentication accuracy. However, their study is limited by its lack of comprehensive datasets, restricting the scope of broader analysis. In contrast, our research emphasizes evaluating password strength against brute-force attacks rather than solely focusing on authentication accuracy.

Mengli Zhang et al. [18] introduced the SPSR-FSPG model, combining PCFG and RNN to enhance password generation by examining password structures. This innovative approach led to a notable improvement in the coverage of actual passwords. However, the study also pointed out certain quality concerns, including issues with duplicates and reporting delays, which could compromise the consistency of the research findings. In contrast, our research takes a different direction by examining how password length and complexity influence resistance to cracking rather than focusing on password generation models.

Simone Raponi and Roberto [19] analyzed password management practices across major websites in the EU, revealing critical weaknesses in password recovery protocols. Their study found that 28 websites face serious security threats, with over 44.12% showing vulnerabilities. The research also highlights a gap in compliance with GDPR, as many sites have not improved their password management despite regulatory enforcement. Unlike their focus on website security practices, our study examines the effectiveness of password length and complexity in resisting brute-force attacks.

Zhiyang Xia et al. [20] introduced the GENPass model, combining neural networks and PCFG to enhance password generation. Their results show a 20% higher matching rate compared to dataset-only approaches. However, the study highlights a limitation in current models, as they focus on single-site testing, reducing effectiveness on unknown datasets. In contrast, our research investigates the impact of password complexity and length on cracking resistance across various hashing algorithms, addressing the broader applicability of password security.

Zhijie Xie et al. [21] introduced the GuessFuse framework, combining multiple passwordguessing techniques to improve cracking performance. Experimental results indicate a notable improvement in success rates, ranging from 4. 70% to 17. 66% with the use of five distinct guess lists. While this study highlights a significant gap regarding effective integration strategies for password-guessing models, our research takes a different approach. We focus on analyzing the influence of password length and complexity on resistance to brute-force attacks across various hashing algorithms. In doing so, we address this gap by exploring real-world attack scenarios. Mushtaq Ali et al. [22] tackled two key issues in reformation-based password schemes: the balance between client-side security and usability and insufficient server-side security from storing actual passwords. Their proposed scheme improves both security and usability by eliminating the need for manual computation or extra devices. While the scheme enhances security on both sides, it lacks testing with a larger user base. Unlike their focus on usability and

security, our research investigates the impact of password complexity and length on resistance to brute-force attacks, addressing a different aspect of password security.

Yuhong Mo et al. [23] used the RoBERTa algorithm to assess password complexity, achieving high accuracy rates above 99.7% in two training sessions. However, they note a key limitation in the model’s applicability to real-world scenarios, which remains an area for future research. In contrast, our study focuses on password length and complexity’s effect on resistance to bruteforce attacks across multiple hashing algorithms, addressing practical vulnerabilities in password security.

Sirapat Boonkrong et al. [24] addressed password insecurity by developing an application that measures strength using four key metrics: entropy distribution, likelihood of compromise, effective length, and cracking time. While the app helps users understand password composition and strength, it lacks real-world testing to assess its effectiveness against actual cyber threats. Unlike their focus on password strength metrics, our research examines how password length and complexity impact resistance to brute-force attacks across various hashing algorithms.

Stephen Kahara Wanjau et al. [25] developed a supervised deep learning method using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to detect SSH brute-force attacks. The model achieved high accuracy (94.3%) and precision (92.5%), demonstrating strong performance. However, the study points to a gap in feature selection techniques, which could further enhance the model’s effectiveness. In contrast, our research focuses on the impact of password length and complexity on brute-force attack resistance rather than detection methods, addressing a different aspect of password security.

Richard Shay et al. [26] investigated password-composition policies to balance security and usability. Their findings suggest that the 3class12 and 2word16 policies are more user-friendly and secure compared to the commonly used comp8 policy. However, the study is limited by its focus on a small set of policies and a single dataset, which may not reflect the full range of attack strategies. Unlike their work, our research focuses on the impact of password length and complexity on resistance to brute-force attacks across multiple hashing algorithms.

Suyun Borjigin [27] introduced a dual-password authentication system to address credential theft and remote attacks. By separating the login and authentication passwords, the system enhances security against non-local login attacks. However, the study lacks a clear identification of research gaps, making it difficult to suggest areas for future exploration. In contrast, our research focuses on the effect of password length and complexity on resistance to brute-force attacks, addressing practical vulnerabilities in password security.

Joshua Tan et al. [28] conducted an empirical analysis on the effectiveness of various password policy components, such as length, character diversity, blocklists, and minimum strength requirements. Their findings show that combining minimum length and strength criteria improves password security. However, the study overlooks the impact of different types of blocklists on security outcomes. In contrast, our research focuses on the effects of password length and complexity on resistance to brute-force attacks, filling in the gap left by their study regarding attack scenarios.

S. Cem Şahin et al. [29] aimed to define and distinguish between ‘password complexity’ and ‘strength,’ offering a framework that considers factors like an attacker’s computational resources, time, and prior knowledge. Their study highlights a gap in existing frameworks, as they often neglect human biases and realistic attacker methods in assessing password strength. In contrast, our research examines how password length and complexity impact resistance to brute-force attacks, addressing a more practical perspective of password security

S. Vaithyasubramanian et al. [30] explored the effectiveness of Markov Passwords against bruteforce attacks, using the Markov chain model to generate robust alphanumeric passwords. Their tests on 40 randomly generated passwords revealed the time required to crack them through brute-force methods. However, the study lacks an analysis of the long-term effectiveness of Markov Passwords in real-world scenarios, suggesting the need for further longitudinal research. In contrast, our research focuses on how password length and complexity impact resistance to brute-force attacks.

Binh Le et al. [31] reevaluated the effectiveness of traditional Markov-based Password Strength Meters (PSMs) and introduced innovative models like the Simple Markov Model (SMMl) and the Layered Markov Model (uLMM). Their findings show that the SMMl-PSM model, incorporating password length, is effective in identifying weak passwords. However, the study overlooks how factors like keyboard layout and Leet transformations affect password strength, suggesting an area for future research. Our research, on the other hand, investigates the broader impact of password complexity and length on security when subjected to brute-force attacks.

Jianhua Song et al. [32] introduced Alphapwd, a password generation method that uses mnemonic shapes to enhance both security and usability. Their findings show that Alphapwdgenerated passwords are more resilient against unknown attacks compared to conventional passwords. The study also highlights a gap in current password composition policies, emphasizing the need to balance security and user-friendliness, as many existing strategies prioritize protection over usability. In contrast, our research focuses on analyzing the relationship between password length, complexity, and resistance to brute-force attacks, addressing a different aspect of password security.

Aikaterini Kanta and Mark Scanlon [33] introduced an innovative approach to generating customized dictionary lists based on specific topics or user interests using contextual information. Their findings show that contextual dictionaries can increase password-cracking success rates by up to 15.5% compared to conventional methods. The study highlights a gap in the lack of automated techniques for extracting and using contextual information in password cracking, suggesting that developing these methods could enhance attack effectiveness. In contrast, our research focuses on the impact of password length and complexity on resisting brute-force attacks, offering a different perspective on password security.

Chowdhury [34] systematically evaluated different metrics for assessing password quality, introducing a novel complexity measure through an Entropy-Based Combinatorial Methodology. The research found a strong correlation between password difficulty and quality, indicating that more robust passwords are harder to breach. The study also identifies a gap in refining the Combinatorial Entropy Algorithm to address emerging patterns and evolving cyber threats. In contrast, our research examines how password length and complexity affect resistance to bruteforce attacks across various hashing algorithms, focusing on practical vulnerabilities.

Ibrahim Alkhwaja et al. [35] analyzed the effectiveness of various hardware configurations in parallel brute-force and dictionary attacks, achieving significant speed improvements—1.9 times faster for brute-force cracking using six cores and 4.4 times more efficient dictionary attacks with eight-core processing. The study highlights a limitation in current passwordcracking techniques, which struggle to adapt to the increasing complexity of password policies, such as longer lengths and more diverse character sets. Unlike their focus on cracking methods, our research investigates the role of password length and complexity in strengthening security against brute-force attacks.

Katha Chanda [36] explored the factors that enhance password strength and the challenges in cracking them. The study introduced PwdStrength, a password strength checker that classifies passwords as ‘weak,’ ‘fair,’ ‘strong,’ or ‘invalid,’ while updating its database to include commonly used passwords to defend against brute-force attacks. The research highlights a gap in exploring alternative authentication methods beyond traditional passwords, which could improve usability and address user hesitance. In contrast, my research uses Random Forest to classify passwords as strong, medium, or weak based on their characteristics, enhancing password security evaluation.

Javier Galbally et al. [37] introduced an advanced multimodal technique for measuring password strength, tested through a comprehensive experimental framework. Their unified methodology integrates multiple techniques for a more thorough password strength evaluation. The study’s findings come from two experiments assessing this new approach’s efficacy. However, the research highlights the need for further evaluations across a broader range of password strength indicators to strengthen the results. In contrast, my research uses Random Forest combined with Zxcvbn to classify passwords, offering a more detailed evaluation of password security.

Seok Jun and Byung Lee [38] introduced innovative ChatGPT-based metrics for assessing password security strength. Their method uses these prompt metrics to flexibly and adaptively evaluate password strength without the need for additional model training. The study highlights a strong correlation between the LUDS metric and the Complexity score, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.7281. However, the research points out a limitation in the relatively weak correlation (0.4717) between the Zxcvbn metric and memorability, indicating difficulties in assessing how memorable passwords are. In contrast, my research combines Random Forest with Zxcvbn to classify passwords, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of password strength and security

Tanvi Gautam [39] explored various password-cracking methods, focusing on brute-force attacks, dictionary attacks, and rainbow table attacks. The research emphasizes the importance of strong password policies in mitigating vulnerabilities associated with these techniques. However, a gap exists in understanding the psychological factors influencing users’ password choices. Addressing this could help explain why certain passwords are more vulnerable to compromise than others. In contrast, our research investigates the role of password length and complexity in strengthening security against brute-force attacks.

Table 1. Summary of Key Findings from Previous Studies

3. METHODOLOGY

This section will provide a thorough overview of the proposed model and the tools utilized in its development.

In this research, we used an experimental methodology to examine how password length and complexity affect the effectiveness of brute force attacks. This involved running experiments on 30 different passwords and measuring the expected time to crack each one. Passwords are encrypted using four distinct algorithms: MD5, SHA-256, Bcrypt, and Argon2. The main objective of this study is to analyse the strength and complexity of a password for brute force attacks based on its unique characteristics and the time taken to crack that password. To simulate brute force attacks and evaluate the effectiveness of different types of passwords, we will use programming tools such as Python, along with libraries such as hashlib and Plotly. Random Forest Classifier and Zxcvbn were also used. Random Forest Classifier was used to measure the length of the word and classify it (weak, medium, strong, very strong). The goal of using it with the Zxcvbn algorithm was to increase the accuracy of password analysis and evaluation, as the Zxcvbn algorithm evaluates the password from 0 to 4. Passwords were not measured based on encryption algorithms but rather were evaluated based on their length and complexity. However, the hashing algorithm for each password was saved in an Excel file. Each hashing algorithm has its properties; for example, MD5 is regarded as outdated and insecure due to its numerous vulnerabilities and its reliance on a 128-bit (16-byte) hash value. While it has traditionally been used to verify the integrity of data against alterations and to check file integrity, it is no longer recommended for applications that demand high security. The SHA-256 algorithm is part of the SHA family of cryptographic hash functions, and it produces a hash value that is 256 bits long,

equivalent to 32 bytes. It offers enhanced security compared to MD5 and is commonly utilized in various applications, including cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, data integrity verification, and digital signatures. With its resilience against collision attacks, SHA256 is a far more secure choice than MD5 [40]. Also, Bcrypt was used. This algorithm is specifically designed to store passwords securely. When compared to earlier algorithms, it stands out as the most secure option available, largely due to its use of a technique known as salting. Salting involves adding a random value to the password before it undergoes the hashing process. This approach considerably increases the difficulty for attackers attempting to carry out brute force attacks [41]. Finally, the Argon2 algorithm, which is a prominent key derivation.

Function that emerged as the champion of the Password Hashing Competition in July 2015. This innovative creation was designed by Alex Biryukov, Daniel Dinu, and Dmitry Khovratovich, who are affiliated with the University of Luxembourg. Argon2 employs the BLAKE2 hash algorithm to effectively and securely scramble the input data, which includes both the password and the salt [42].

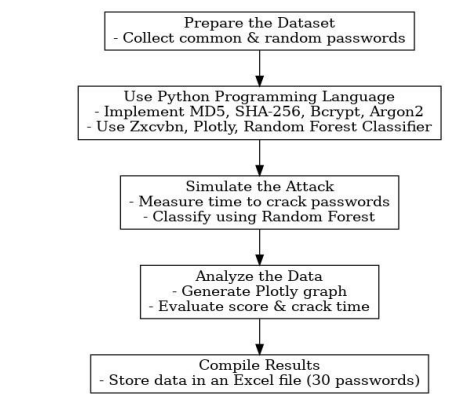

3.1.Flowchart

Figure 1 presents the flowchart, which can be summarized in the following steps:

1. Collect common and random passwords users are used to using to protect their accounts.

2. Use 4 hashing algorithms to encrypt passwords and Zxcvbn algorithm and Random Forest

Classifier to evaluate passwords.

3. Simulate the attack by measuring the time it takes to crack each password.

4. Analyze passwords using Plotly in a graph.

5. Store passwords and all results in an Excel file.

Figure 1. Flowchart

3.1.1. Dataset Collection

The dataset used in the research consisted of 30 passwords selected randomly, with various lengths and complexities tested, incorporating symbols, uppercase and lowercase letters, and numbers. Some of the passwords were commonly used ones taken from leaked password datasets, while others were randomly selected. These passwords were chosen to represent reallife scenarios, as many users are unaware of the importance of password complexity and length.

3.1.2. Feature Selection

We use 4 hashing algorithms to store and keep the information secure, and encryption was applied to each password after evaluating its strength.

Zxcvbn and Random Forest Classifier have been combined to accurately evaluate passwords as an algorithm in that zxcvbn is a password strength estimator developed with insights from password cracking techniques. It identifies and evaluates more than 40,000 frequently used passwords through pattern recognition and conservative estimations. The tool effectively filters out common first and last names, well-known words from Wikipedia, and other widely used terms across various cultures. Additionally, it detects typical patterns such as dates, repeated sequences (like ‘1111’), repetitive strings (such as ‘abcabc’), and random keyboard combinations (like ‘qwertyuiop’) [43].

The Random Forest Classifier is a versatile and easy-to-use machine-learning algorithm that often delivers impressive results, even without extensive hyperparameter tuning. Its adaptability and flexibility contribute to its status as one of the most widely used algorithms, making it wellsuited for both classification and regression tasks. It measured the length of the password and classified the password into four classes (weak, medium, strong, and very strong) [44].

3.1.3. Evaluation

The attack was simulated, and each password was evaluated using the combination of Zxcvbn and Random Forest Classifier algorithms. The time taken to crack the password was also simulated using two types of attacks: offline and online.

3.1.4. Analyzation

Every 30 passwords were analyzed through a graph using the Plotly library, and the time to crack the password was evaluated. Also, the score is recorded for each password from 0 to 4 to be clear and easy to understand.

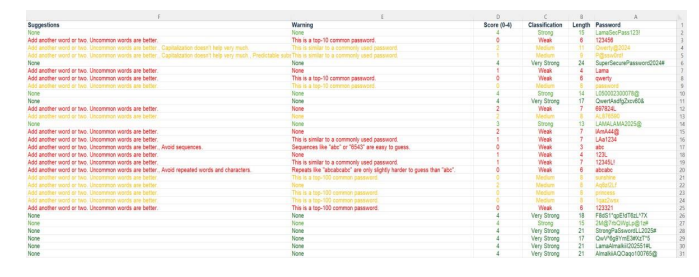

3.1.5. Save Data

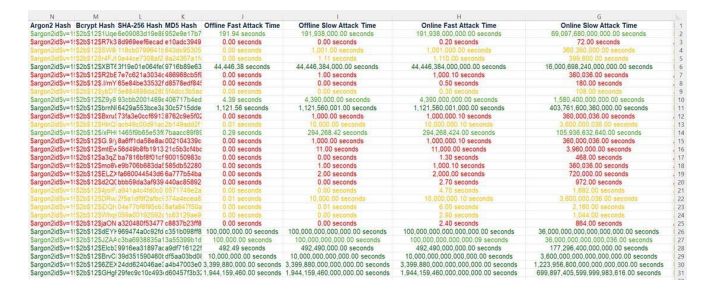

Every 30 passwords are stored in an Excel file showing all aspects of the evaluation including password, length, rating, score (0-4), warning that appears if the password is less than 4, suggestion to improve each password to become stronger, time taken to crack the password and four hashing algorithms.

3.2. Results and Discussion

In this section of the research, we will examine the results by evaluating 30 passwords based on their length, strength, and the time taken to crack them. The duration required to crack a single password was analysed across four methods: online slow, online fast, offline slow, and offline fast.

Online attacks pose a prevalent threat, capable of targeting web applications, exposed SSH terminals, and virtually any login interface. However, these attacks face two important limitations.

First, their effectiveness is limited by network speed. Second, online password attacks often create significant noise; numerous failed attempts to enter the wrong password can activate security protocols. For instance, after a set number of unsuccessful tries, the targeted account might be locked, or the attacker’s IP address may be blocked, preventing any further access.

Offline attacks: This type of attack occurs when an attacker gains access to a database containing encrypted passwords (hashes) and attempts to decrypt them without interacting with the target system. The process takes place on the attacker’s own machine, allowing for an unlimited number of attempts. This method is, therefore, much faster than online attacks and benefits from the fact that there is no limit on the number of attempts [45].

Regarding the speed of different types of attacks:

Very fast: In online attacks, thousands of attempts can be made per second, while in offline attacks, millions of guesses can be attempted per second.

Slow: In online attacks, only a few attempts can be made at long intervals, whereas in offline attacks, a few hundred to thousands of guesses per second are possible.

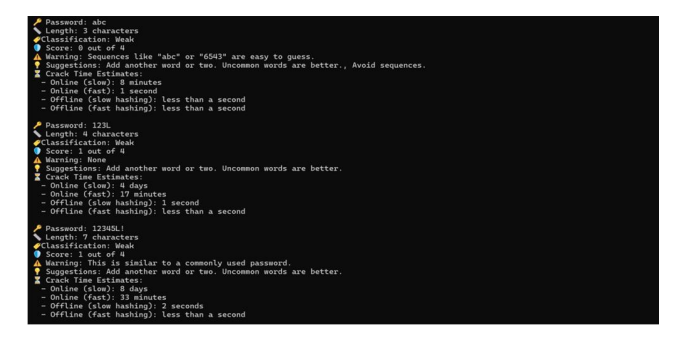

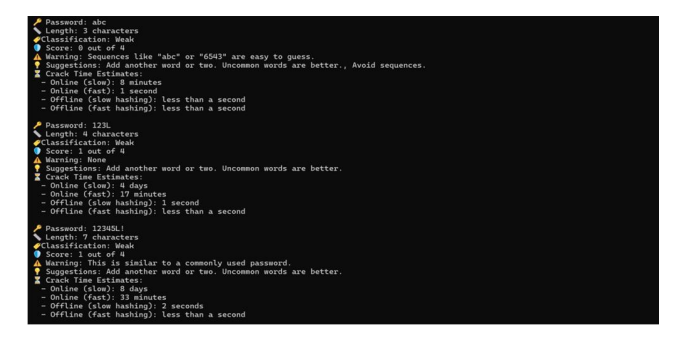

Figure 2. 3 weak passwords results

In Figure 2, the password “abc,” consisting of just three characters, has been categorized as weak. This classification is due to its commonality and the absence of uppercase letters, symbols, or numbers. The zxcvbn algorithm assigned a score of 0 to this password, signifying it as extremely weak. Furthermore, the algorithm issued a warning related to this score and recommended ways to enhance the password’s strength.

In terms of security, the time required to crack this password was found to be remarkably short— less than 10 minutes. This highlights the significant vulnerability of simple, threecharacter passwords to brute-force attacks.

The passwords “123L” and “12345L! ” illustrate how minor modifications can impact security. The first password simply added an uppercase letter, while the second included a symbol, resulting in a slight score increase of just one point. Despite this small improvement, both passwords were still deemed weak. Interestingly, the password “12345L! ” took longer to crack due to its marginally higher complexity, emphasizing the importance of diversity in password composition.

These findings suggest that while incorporating elements like uppercase letters or symbols can provide a slight enhancement in security, they are inadequate against more sophisticated attacks. This highlights the critical need for a varied combination of characters to truly bolster password strength.

Figure 3. 3 passwords results

In Figure 3, we see that the password “LAMALAMA2025@”, which consists of 13 characters and includes uppercase letters, numbers, and the @ symbol, has been categorized as strong. However, the zxcvbn algorithm rated it with a score of 3. This rating implies that while the password is relatively secure, it still needs adjustments to reach a score of 4, which would be classified as very strong. The algorithm takes into account factors beyond mere length and character variety, such as identifiable patterns or repetitions that could be exploited in a potential attack.

Notably, despite the password’s complex makeup, the time required to crack it through a rapid offline attack was surprisingly brief—taking less than a second to breach successfully. This underscores an important concern: even a password that appears to be robust may still possess predictable patterns or vulnerabilities, rendering it susceptible to efficient cracking methods such as precomputed hash attacks or dictionary-based approaches.

The password “lAmA44@”, which has 7 characters, has been deemed weak despite its combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and a special character. This highlights the importance of length in determining password strength—passwords with only 7 characters, regardless of their variety, remain vulnerable to rapid brute-force attacks.

Similarly, the password “LAa1234,” also composed of 7 characters, received a weak rating of 1. This low score is primarily due to its status as a commonly used password, its lack of sufficient complexity, and its relatively short length. Consequently, this emphasizes the need to steer clear of typical password patterns and to prioritize both length and complexity to improve security.

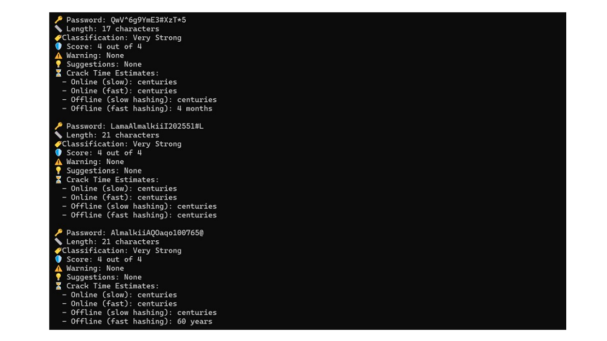

Figure 4. 3 Strong passwords results

Figure 4 displays three passwords, each composed of either 17 or 21 characters, which were classified as very strong, achieving a score of 4. Their impressive strength can be attributed to a combination of length, character diversity, and complexity, making them highly resistant to attacks. Estimates suggest that cracking these passwords would take years or even centuries, underscoring their robustness against contemporary brute-force and dictionary attack methods. However, it is crucial to remember that while the passwords’ length and complexity provide substantial security, the estimated time to crack them also hinges on factors such as the attacker’s computational power and the employment of advanced techniques, like parallel processing or GPU-based cracking. This underscores the importance of continuously reassessing password security in light of evolving computational capabilities.

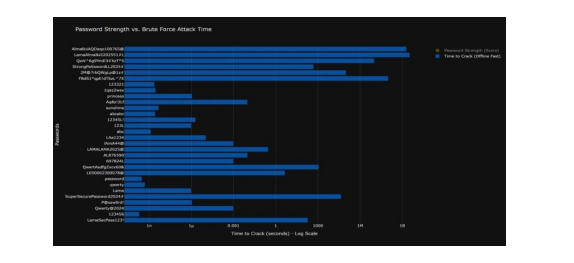

To enhance the understanding of the time needed to crack each password, we created a graph using the Plotly library. This visual representation highlights the estimated cracking times for various passwords, clearly demonstrating the significant disparity in security between long, complex passwords and their shorter, simpler counterparts.

Figure 5.Passwords Strength vs. Brute Force Attack Time

The time scale at the bottom of the chart utilizes a logarithmic scale in Figure 5, which means that each increment reflects an exponential increase instead of a linear one. This format effectively illustrates a vast range of time values, making the information more accessible. The numbers indicate the estimated duration to crack passwords through a rapid offline brute-force attack.

The offline Fast Attack type was analysed because it is the fastest, and the time taken to crack each password was evaluated as follows, and the results are shown in Figure 6:

1n: means that the password can be cracked in a billionth of a second, and the password, in this

case, is considered very weak.

1µ: is at the same level as a nanosecond, and a password that can be cracked in a millionth of a

second is considered weak.

0.001: The password here can be cracked in a thousandth of a second, and here the password is

considered easy and can be hacked easily.

1: The attack can successfully crack the password within one second.

1000: The password can be cracked in approximately 17 minutes.

1M: Here, the attacker will take 11 days to crack the password.

1B: Here the password is considered strong because the attacker will take about 32 years to crack

it and the password here is classified as very strong.

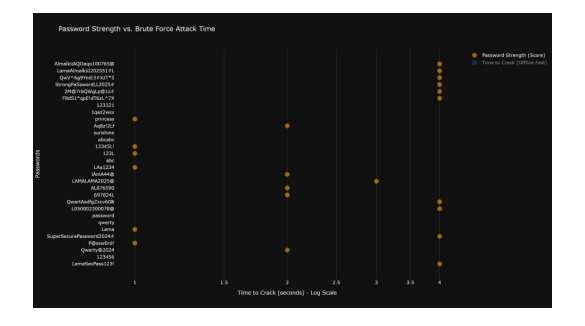

Figure 6Passwords Strength (Score )

The strength of thirty passwords is presented in Figure 6, offering a clear visual representation of each password’s rating. These ratings, which range from 0 to 4, indicate different levels of security: a rating of 0 signifies very weak passwords, while a rating of 4 denotes very strong ones. This grid effectively allows for quick comparison of the passwords, emphasizing how factors such as length, complexity, and character diversity contribute to improved security.

Figure 7The Excel File

Figure 8 The Excel File

Finally, an Excel file (Figure 7,8) was created for each password, containing its length, classification, score, warnings, suggestions, and estimated attack times for both online (fast and slow) and offline (fast and slow) attacks. In addition, each password was saved with its hash using four algorithms: MD5, SHA-256, Bcrypt, and Argon2 – not for evaluating password strength or complexity, but solely for storage purposes. The classifications were color-coded: red for weak, yellow for medium, light green for strong, and dark green for very strong. From the evaluation and analysis, we conclude that symbols, uppercase and lowercase letters, and numbers are crucial for password security. Passwords consisting of 18 characters, including a mix of numbers, letters, and symbols, were classified as very strong and estimated to take approximately 32 years to crack. It is equally important to refrain from reusing passwords across different

systems or websites

Our study is compared with the study by Kumar and Reddy (2020), “An efficient security model for password generation and time complexity analysis for password cracking.” Both studies emphasize the importance of password length and complexity. Our approach differs in several key aspects.

In experimental validation, the previous study focused on the Random Character Usage (RCUH) model for password generation. Our study tested real-world passwords against multiple hashing algorithms and simulated brute force attacks under different conditions (online/offline, fast/slow).

Regarding the diversity of algorithms, Kumar and Reddy (2020) evaluated passwords based on entropy calculations. Our study included Zxcvbn and Random Forest Classifier, which provide a more practical assessment of password complexity and security.

The previous study proposed a new approach for password generation but did not compare the results extensively with brute force resistance metrics. However, our study provides a clear comparison of how different password structures withstand real-world attacks and provides actionable security recommendations and suggestions.

While both studies emphasize the importance of password complexity, our research takes a step further by incorporating practical implementation, testing, and simulation to offer a real-world perspective on password security. Our findings not only support previous research highlighting the significance of entropy but also reveal how factors such as password length and diversity play a crucial role in enhancing resistance to brute force attack

4. FUTURE WORK

While this study tested 30 passwords, this sample size may not fully capture the diversity of password choices in real-world scenarios. Future research could expand the dataset to include a significantly larger and more representative sample of passwords from various sources, including those commonly used in different domains such as social media, banking, and enterprise environments.

In addition, the passwords analyzed in this study were exclusively in English. Future studies could extend the analysis to include passwords in multiple languages, considering linguistic and cultural variations in password creation. Some languages may use different character sets, diacritics, or unique patterns that could impact password strength and vulnerability to attacks.

Furthermore, future research could explore more sophisticated attack methodologies. While this study primarily focused on brute force and dictionary attacks, future work may simulate hybrid attacks, which combine multiple attack techniques and AI-based guessing methods. Specifically, machine learning models such as Transformer-based architectures (e.g., GPT) or recurrent neural networks (RNNs) could be trained on large datasets of breached passwords to predict and crack passwords more efficiently. Evaluating how AI-driven attacks compare to traditional methods could provide deeper insights into emerging security threats.

An essential direction for future efforts is the incorporation of multi-factor authentication (MFA) as an extra layer of security. While password strength is crucial, MFA can significantly reduce the risk of unauthorized access even if a password is compromised. Future research could explore how different MFA mechanisms, such as biometric authentication (e.g., fingerprint recognition, facial recognition), hardware tokens, and time-based one-time passwords (TOTP), impact overall security when combined with strong password policies. Additionally, alternative authentication methods such as passkeys, public key cryptography, and decentralized identity verification could be evaluated as potential replacements for traditional password-based authentication.

Finally, future studies could investigate user behavior and password management practices, including how individuals create, store, and reuse passwords. Understanding these behaviors could help in designing more effective password policies and security awareness programs to encourage users to adopt stronger authentication methods. Moreover, behavioral biometrics (e.g., typing patterns and mouse dynamics) could be explored as an additional security layer that continuously verifies user identity beyond the initial login phase.

5. CONCLUSION

In this study, we investigated how the length and complexity of passwords affect their resistance to brute force attacks. The findings indicate that longer passwords greatly enhance the number of potential combinations, thereby strengthening security. Each additional character significantly increases the difficulty faced by attackers trying to guess passwords using brute force techniques. However, it is important to note that simply increasing password complexity does not result in a proportional increase in security. Complex passwords, especially shorter ones, can still be vulnerable to advanced brute force tools, which can rapidly test a vast number of combinations. Thus, prioritizing password length over complexity may provide more effective protection against such attacks.

Organizations should implement security policies that emphasize password length as a primary defense mechanism while also promoting multi-factor authentication (MFA) to mitigate risks associated with compromised credentials. Additionally, adopting alternative authentication methods, such as passkeys and biometric verification, can further enhance security and reduce reliance on traditional passwords. Regular security awareness training and enforcement of password best practices can help users create and manage stronger authentication credentials.

REFERENCES

[1] Morris, R., & Thompson, K. (1979). Password Security: A Case History. Communications of the ACM, 22(11), 594-597.

[2] The history and future of passwords. (2025, February 12). Beyond Identity

[3] Bellovin, S. M., & Merritt, M. (1992). Encrypted Key Exchange: Password-Based Protocols Secure Against Dictionary Attacks. Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Symposium on Research in Security and Privacy, 72-84.

[4] Florêncio, D., & Herley, C. (2007). A Large-Scale Study of Web Password Habits. Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on World Wide Web, 657-666.

[5] NIST special publication 800-63B. (n.d.).

[6] Brute force attack: Definition and examples. (2023, June 30).

[7] Popular tools for brute-force attacks [updated for 2020]. (n.d.). Cybersecurity Training & Certifications | Infosec.

[8] Zamel, S. H. (2019, July 18). Europe, Middle East and Africa a hotspot for brute force attacks. Saudi Shopper

[9] Kaspersky blocks over 330,000 attacks on IoT devices in the Middle East in 2022. (2023, March

28). Eye of Riyadh

[10] Hydra | Kali Linux tools. (n.d.). Kali Linux.

[11] What is a brute force attack? | Definition, types & how it works. (n.d.). Fortinet.

[12] Definition of password. (n.d.). PCMAG.

[13] Weak password. (n.d.). Acunetix.

[14] How long should my password be? (n.d.). Bitwarden.

[15] Touil, H., Akkad, N. E., Satori, K., Soliman, N. F., & El-Shafai, W. (2024). Efficient braille transformation for secure password hashing. IEEE Access, 12, 5212-5221.

[16] Kumar, B. P., & Reddy, E. S. (2020). An efficient security model for password generation and time complexity analysis for cracking the password. International Journal of Safety and Security Engineering, 10(5), 713-720.

[17] Parkinson, S., Khan, S., Crampton, A., Xu, Q., Xie, W., Liu, N., & Dakin, K. (2021). Password policy characteristics and keystroke biometric authentication. IET Biometrics, 10(2), 163-178.

[18] Zhang, M., Zhou, G., Khurram Khan, M., Kumari, S., Hu, X., & Liu, W. (2019). SPSR-FSPG: A fast simulative password set generation algorithm. IEEE Access, 7, 155107-155119.

[19] Raponi, S., & Pietro, R. D. (2020). A longitudinal study on web-sites password management (in)Security: Evidence and remedies. IEEE Access, 8, 52075-52090.

[20] Xia, Z., Yi, P., Liu, Y., Jiang, B., Wang, W., & Zhu, T. (2020). GENPass: A multi-source deep learning model for password guessing. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 22(5), 1323-1332.

[21] Xie, Z., Shi, F., Zhang, M., Ma, H., Wang, H., Li, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2024). GuessFuse: Hybrid password guessing with multi-view. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 19, 4215-4230.

[22] Ali, M., Baloch, A., Waheed, A., Zareei, M., Manzoor, R., Sajid, H., & Alanazi, F. (2021). A simple and secure Reformation-based password scheme. IEEE Access, 9, 11655-11674.

[23] Yuhong Mo, Shaojie Li, Yushan Dong, Ziyi Zhu, & Zhenglin Li. (2024). Password Complexity Prediction Based on RoBERTa Algorithm.

[24] Sirapat Boonkrong, Arkalerk Kitthimon, Patchara Koksoungnoen, & Krissada Jenprakhon. (2021). Password Strength Meter Application.

[25] Wanjau, S. K., Wambugu, G. M., & Kamau, G. N. (2021). SSH-brute force attack detection model

based on deep learning. International Journal of Computer Applications Technology and Research, 10(01), 42-50.

[26] Shay, R., Komanduri, S., Durity, A. L., Huh, P. (., Mazurek, M. L., Segreti, S. M., Ur, B., Bauer, L., Christin, N., & Cranor, L. F. (2016). Designing password policies for strength and usability. ACM Transactions on Information and System Security, 18(4), 1-34.

[27] Suyun Borjigin. (2021). A Dual-Password Login-Authentication Mechanism.

[28] Tan, J., Bauer, L., Christin, N., & Cranor, L. F. (2020). Practical recommendations for stronger, more usable passwords combining minimum-strength, minimum-length, and Blocklist requirements. Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security.

[29] S. Cem, Ahin, Robert Lychev, & Neal Wagner. (2024). General Framework for Evaluating Password Complexity and Strength.

[30] Vaithyasubramanian, S., Christy, A., & Saravanan, D. (2014). An analysis of Markov password against brute force attack for effective web applications. Applied Mathematical Sciences, 8, 5823-5830.

[31] Thai, B. L., & Tanaka, H. (2024). A study on Markov-based password strength meters. IEEE Access, 12, 69066-69075.

[32] Song, J., Wang, D., Yun, Z., & Han, X. (2019). Alphapwd: A password generation strategy based on mnemonic shape. IEEE Access, 7, 119052-119059.

[33] Kanta, A., Coisel, I., & Scanlon, M. (2022). A novel dictionary generation methodology for contextual-based password cracking. IEEE Access, 10, 59178-59188.

[34] Chowdhury. (2024). Analyzing Password Strength: A Combinatorial Entropy Approach.

[35] Lkhwaja, I., Albugami, M., Alkhwaja, A., Alghamdi, M., Abahussain, H., Alfawaz, F., Almurayh, A., & Min-Allah, N. (2023). Password cracking with brute force algorithm and dictionary attack using parallel programming. Applied Sciences, 13(10), 5979.

[36] Chanda, K. (2016). Password security: An analysis of password strengths and vulnerabilities. International Journal of Computer Network and Information Security, 8(7), 23-30.

[37] Galbally, J., Coisel, I., & Sanchez, I. (2017). A new multimodal approach for password strength estimation—Part II: Experimental evaluation. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 12(12), 2845-2860. [33]

[38] Lee, B. M. (n.d.). A novel approach to password strength evaluation using chatgpt-based prompt metrics_supp1-3503653.pdf.

[39] Tanvi Gautam. (2024). Investigation of Password Cracking Methodologies.

[40] Jena, B. K. (2021, July 13). What is SHA-256 algorithm: How it works and applications |

Simplilearn. Simplilearn.com.

[41] BCrypt algorithm. (n.d.). Topcoder.

[42] Overview of Argon2: A memory hard function for password hashing. (n.d.). Gist.

[43] Introduction | zxcvbn-TS. (n.d.). GitHub Pages.

[44] Random forest: A complete guide for machine learning. (2021, July 22). Built In.

[45] Miller, M. (2021, March 22). What’s the difference between offline and online password attacks? TriaxiomSecurity.