IJCNC 02

ENHANCING CONGESTION CONTROL USING A LOAD-BALANCED ROUTING ALGORITHM FOR DISTRIBUTED NETWORKS

Jogendra Kumar

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, G.B.Pant Institute of Engineering and Technology, Ghurdauri, Pauri Garhwal Uttarakhand, India

ABSTRACT

Ad hoc networks frequently encounter congestion due to packet loss, link failures, and limited bandwidth. These issues lead to significant energy and time expenditures for congestion recovery, ultimately degrading network performance. Various techniques exist to mitigate the effects of congestion, and this paper introduces a novel routing protocol named Load-Balanced Congestion-Adaptive Routing (LBCAR) protocol, which incorporates a random route point model in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks. The paper promotes an adaptive load-balanced routing approach combined with congestion control. A hybrid protocol is proposed to address congestion control and achieve optimal performance. The algorithm integrates metrics such as traffic density, routing path lifetime, and link failure detection to enhance network performance. The results of the proposed approach are compared with those of other routing protocols to assess its effectiveness.

KEYWORDS

AdHoc networks, Congestion control, data delivery, Load balancing, Mobile Networks

1. INTRODUCTION

Ad hoc wireless networks are very popular due to their reliability & capacity to balance traffic and congestion control, QoS without much infrastructure. Such quality makes it very useful for multiple applications since all network controls are with only nodes making it less energy efficient. To save critical energy which is limited for any node we need a dynamic protocol that can save energy and create a routing infra that can be established dynamically with self- establishing and self-management on the needed times [1-2]. The possible utilization of ad hoc networking incorporates business partners sharing data during a meeting, students utilizing workstations, and laptops to take part in a lecture, emergency disaster relief personnel organizing endeavors after a seismic tremor or storm, and soldiers handing off data for situational awareness on the war zone [3]. During the simulation process in any random allocation of nodes, every mobile node initiates from and forward to a random location [4]. Every node stays fixed for a predetermined timeframe which is called delay time and subsequent moves in an actual line to a few up-to-date arbitrarily picked areas at an arbitrarily picked acceleration to the predefined maximum speed. When arriving at that new area, the node stays there for the delay time and afterward picks another irregular location to continue the transmission process at some changed arbitrarily picked speed, the node keeps on rehashing this conduct all through the execution time [4-5]. It is found that this technique can create a lot of qualified node development and network geography change [6-7]. Congestion is a major issue in MANET. It happens because of reasons including the conduct of the multiple routers, hosts, the multiple transmission among routers, and the media, and happens because of restricted assets at any phase of the route. Congestion happens because users send a greater number of data than the network hosts can oblige, subsequently making the buffer on such hosts top off and plausibility of flood prevails. The result of this can be packet loss, and delay in delivery, and also leads to a decrement in the overall performance of the network [8-9]. So, to diminish congestion, any protocol performing a routing process ought to diminish the quantity of data packets in the network. In any case, essentially dropping flooded packets will decrease information loyalty and increase energy dissemination. A lot of studies had been proposed before, which tended to few of the performance features only. Different methods have been created in an endeavor to limit congestion in ad hoc networks. Moreover, a simple utilization of multipath routing plans could provocatively influence the lifetime network as the collapse pace of energy will be higher [10-11]. This paper is structured into six main sections. Section 1 offers an introduction to the research, summarizing the core concepts. Section 2 covers related work, exploring existing studies that provide foundational insights and guide the creation of a new framework. Section 3 discusses the proposed approach, explaining the methodology and algorithm used in the research. Section 4 delves into the design of both the simulations and the framework. Section 5 presents and analyzes the results, assessing optimization based on the simulation factors outlined earlier. Lastly, Section 6 provides the conclusion and discusses potential areas for future research.

2. RELATED WORK

One of the core challenges in these models is achieving an optimal combination for enhanced quality of management in MANETs. However, some relevant approaches have been identified in the literature. For instance, in [12-13], the authors proposed a flexible Genetic Algorithm aimed at optimizing channel allocation in mesh wireless networks. A detailed Multi-Objective Cellular Genetic Algorithm was proposed for tracking down an ideal transmission approach in MANETs [14]. In [15] author reviewed the routing protocol named RPL under a heterogeneous traffic design. In [16] authors proposed an improved algorithm dependent on Queue-workload-based conditions (QWL-RPL). This proposed protocol accomplished a dependable way with improvised overall results. The final product demonstrates that all things considered, there is a 12%–30% decrease in delay, a 25%–45% decrease in overheads, a 20%–40% decrease in jitter, and a 5%–30% improvement in PRR. In [17-19] work proposed is about the RCER protocol that utilizes the heterogenic nodes on the basis of their energy level. It consists of two processes; one, to make the whole network extra energy-proficient, the network field is separated into topographical groups, and another; to improve the next-hop selection, RCER endeavors ideal routing in view of energy variance, value of Round-Trip Time and hop-count factors. In addition, in light of processing the estimation of wireless connections and hubs status, this protocol re- establishs routing ways and gives network dependability, and improved data delivery performance. Several researchers proposed many algorithms [20-22] for efficiently handling the limited resources. In [23-24] load distribution approach has been presented for energy efficient MANET routing protocol. To implement the load reduction approach by adjusting the energy utilization of all portable nodes by choosing a route with high energy nodes as opposed to the shortest route [25]. Some MANET routing protocols depend on particular connection layer properties, for example, CTS/RTS control succession utilized by prominent IEEE 802.11, and MAC layers to keep away from impacts because of concealed and uncovered terminals. In particular, before transmitting an information casing the source station sends a short control edge, named RTS, to the getting station declaring the impending covering transmission [26]. Fuzzy logic-based Load-Balanced Congestion Control improves MANET performance by dynamically managing load, reducing packet loss, and enhancing efficiency [27]. The proposed CFRS-CP method estimates route congestion probability using MAC overhead, link quality, neighbor density, and vehicle velocity, leveraging these parameters to optimize routing decisions [28]. The proposed LBCAR algorithm outperforms the other two protocols, especially for applications that require high data transmission rates, fast response times, and energy-efficient operations. Its load balancing and congestion awareness mechanisms play a crucial role in achieving these improvements, making it suitable for use in large-scale and energy-constrained networks such as wireless sensor networks or ad-hoc networks.

3. PROPOSED WORK

The default valuation of parameters utilized as a part of CALB provides direct QoS. In this manner, considering the effect of valuation of parameters on the system execution attempts to find an ideal valuation of parameters for LBCAR before sending. There are 9 parameters utilized as a part of LBCAR where the values of possible combinations of estimation of parameters are huge such as 1011 sets. This inspires to usage the meta-heuristic specifically ideal to handle the combinatory exploration work [29-30]. Though for a weak node, the proficiency of a route recovery system is made in this sort of implies that comparing routes are working to the robust nodes. With the aid of the simulated results, the minimization of data loss and delay making use of the proposed adaptive technology [31].

3.1. Proposed Model

The protocol proposed in this research work is named LBCAR- load-balanced-congestion- adaptive-routing protocol. It is a combination of an energy-efficient and congestion adaptive technique to upsurge the overall throughput value in the system [32-33]. In this protocol, a record of the most recent traffic load assessments is maintained by every node with its nearby nodes in a table called the local table. The route’s lifetime is decided by measurement of connection cost and the congestion position of the route is decided by the measurement of traffic load. The route with greatest life time and low traffic load is chosen for data transmission. This algorithm expects that there are no unidirectional connections in the organization. This protocol essentially restricts the overestimated highest amount of packets communicable over the route consuming most fragile hub through high traffic load power and last lifetime [34-41].

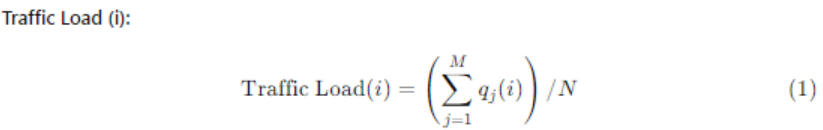

To calculate the traffic load, let’s assume node(xi) as a sample for interface queue length N is the amount of time count for sampling over total execution time qi(j) is jth sample value, This equation computes the traffic load for a node xi,

For the node xi the total length of interface queue is qmax(i) formerly for the node xi the traffic- load-intensity-function is presented as following: The traffic load intensity is the ratio of the node’s actual traffic load to its maximum capacity.

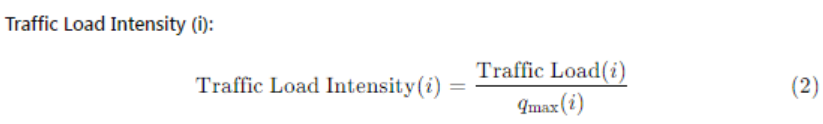

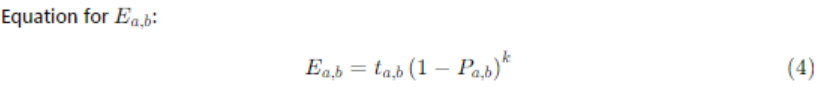

This equation gives the link cost between two nodes a and b.For a link (a, b), link cost [12] has two aspects: first ‘Ea,b’ is link-specific parameter and second is Pa,b node specific parameter or Pa,b is the residual energy of the hub or node. Ea,b is the energy consumed for at least one successful transmission over the link. The link cost is a ratio of the residual energy to the energy required for a transmission.

where Ea,b is the energy consumed for at least one retransmission basic even with connection error and Pa,b is the residual energy of the hub. Ea,b is estimated as

n is number of retransmission over link layer (hop by hop)

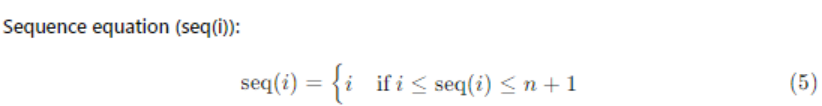

where pa,b is the packet error probability, Ea,b is a single packet transmission energy consumption value. Let the quantity of adjoining hubs of xi is n, and all the functions of power are identified for example (i) value of xi itself, just as the traffic load power. These n+1 value are arranged in the increasing order. These are provided a succession value called as seq(i) and calculated as

The probability of forwarding rate of the information for the hub xi is assumed by the below formula:

pi is identified with the current power of the traffic load of xi. It relies upon overall size of the traffic load in local area of xi. In ad hoc networks, the density of nodes differs from areas and nodes are dynamically distributed. The least the general traffic load is, the bigger the sending possibility, all the nodes will link the route favorably and vice versa. The above equation explained that in particular areas where the power is smaller and n is higher i.e., density is higher, there the routing overhead and redundant forwarding of data both are condensed. Power is also tied to link cost: as the probability of forwarding data decreases, so does the link cost, and the reverse is true as well. In areas where node density is lower and power is higher, the likelihood of establishing a route increases [19]. Along these lines, improvement in life time of the network and load balance to enhance the overall network routinely. At the time of computation, route computed can be ideal, but at the time of simulation the irregular traffic examples will conceivably make the at present chosen ways ideal sooner or later. Thus, LBCAR is a protocol utilized for route selection that incorporates systems for occasional and circulated route selection and computation.

3.2. Network Architecture

Network design and presumptions, study a MANET with enormous amount of hubs conveying by multi-hop paths with one another. The hubs might be laptops, PDAs, or cell phones which may transfer oftentimes. On-demand routing protocol like DSR or AODV are used by nodes for starting multi-hop routing route. In this study we mainly explain the processes of queue in transmission layer management, connection failure recognition and route repair in local region method. As in MANETs, nodes are self-coordinating and autonomous from one another, they can move arbitrarily and regularly. Thus, the link failure may happen because of profoundly decreased received signal strength. Also, the geography of MANETs changes very recurrently, that causes into failure of links between neighbouring nodes. Link failure causes to broken route among source to destination that leads to overall reduction in throughput as well. Hence, this is an independent exploration subject in wireless networks. discovery can be executed utilizing either intermittent CONNECT token messages or connection layer criticism. These CONNECT token messages are neighborhood promotions for the proceeded with incidence of the connection. The nodes in the proposed instrument trade CONNECT token messages intermittently to guarantee link connectivity. The resulting two constraints are related with a CONNECT token message: The amount of highest time span amid two sequential CONNECT token message transportation is named as CONNECT-INTERVAL and the highest number of loss of CONNECT token messages that a hub can endure before it proclaims the link failure is named as CONNECT-LOSS permitted. In the event that a node doesn’t get any CONNECT token message since its neighbor node inside CONNECT-LOSS permitted CONNECT-INTERVAL, at that point the node indicates that the connection is no longer available for data transmission. Local repairing of routes can decrease the impact of link failure on network performance. Link failure reduces the execution of a network significantly. In the existing studies, we have lot of local route repair techniques available. An old method to keep the historical backdrop is known as Query localization method and it overflows the RREQ-route request message to some confined constrained area through local query procedure.

3.3. The CALB Architecture

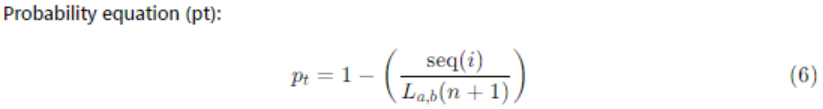

Our proposed strategy leverages the cross-layer storage capability of nodes, spanning both the transmission and network layers. In this approach, when any intermediate node detects a link failure, a route disconnection notification message is generated and directed toward the source node. Upon receiving this notification, all intermediate nodes along the selected route cease forwarding data packets to prevent further transmission.They stored the approaching information parcels in their neighbourhood transmission layer lines When link failure happens to avoid the data losses it collects packets into the transmission layer queue and initiate to find somewhat other fractional temporary way to the receiver node. At the point after the main sender node gets the route disconnection notification control message, it simply breaks the communication of information packets and waits for any further information about new fractional temporary path to the destination. If any fractional temporary path is found, intermediate nodes makes and leads back to the main sender another warning message known as RSN-route-successful-notification. At that point continues its transmission interaction from the transmission layer line. [20]

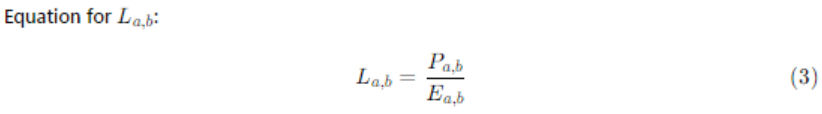

Fig. 1: Message exchange process in CALB

A distinct control message, called a ‘Route Unsuccessful’ (RUN) message, is sent by an intermediate node back to the source node if no partial path is found. Upon receiving the RUN message, the source node initiates a new route discovery process to find an alternative path. Entirely midway nodes continue their communication from the neighborhood buffer in the wake of accepting RSN message. At the point source hub continues the transmission cycle when it gets this RSN message,. The source hub just retransmits the dropped packets during the connection failure. So, as not like the conventional routing protocols, the source node doesn’t have to convey all the information packets. Thus, packet delivery ratio is maximized, the packet drop rate is decreased and inclusive throughput value improved. A congestion-aware routing system is used by CALB so as to provide easy identification of the level of congestion in the network by the nodes and to make a suitable move. In a heavily loaded congested system, nodes stored the packets coming to them even after link failure to diminish packet drop rate. Accordingly, CALB controls the clog in MANET. For a busy network, in CALB the nodes need to send an ALERT message so as not to upsurge the forwarding rate of data to their previous nodes. The buffer packets are collected in their local queues so as to deliver consistent data delivery and to handle congestion mechanisms. Each transitional node keeps a link in the transmission layer for different end-point hubs with the assistance of cross-layer line. Fig. 1 describes the processing, as source node B distributes data packets to A, S, and D as three destination nodes. As the links B to C and C to D are failed which were the original shortest routes to destination D, then node B the storing the information packets in its transmission layer it doesn’t have to imprint any new succession number for every packet during protecting. Moreover, B starts for new partial path and found the route to D as B to E, E to S, S to F, F to G, G to H and finally H to D while it is a longer path as compared to original route. In this way, the transmission layer line is just for temporarily storage of the packets.

3.4. Proposed Algorithm

To handle link failure cases to manage the congestion, nodes can store packets in their limited queue in the transmission layer in CALB processing. Accordingly, every versatile hub plays out some particular capacities as opposed to ordinary portable hubs. We will portray the overall tasks in detail as in the following process. In traditional routing protocols, whenever the source node needed to send packets it begins route route-finding process. It creates a token message as RREQ and broadcast it in the network. Then until any shortest path (route) to the destination is detected source node wait for further activity. furthermore, upon receiving the token message, the receiver node sends a route reply message back to the source node. Each time the sender node receives this route reply message, it initiates the information transmission process.In the event that there happens a connection failure because of node portability or some other reasons like restricted transfer speed, absences of energy, and so on, and if the sender node receives a route failure warning message, it triggers specific actions to address the failure, it further stops transmission of information packets. So, after failure of the shortest path source node restarts another new route discovery cycle to convey the information packets. Source node needed to retransmit the whole set of packets, even if this is longer path than the original shortest path while it diminishes the data delivery rate. In the proposed model, when a link failure occurs, the source node halts its transmission and temporarily waits for a partial path to be established instead of immediately initiating a new route discovery process to the receiver. Once a partial temporary path is found, the source node is notified, allowing it to resume transmission. The decrement in data delivery rate means decrement in the overall performance of the network. The below algorithm shows that the set of all source nodes is S and s is source node, where. The design choices made in the LBCAR algorithm focus on improving network performance, particularly under the conditions of link failures and congestion, by offering a more dynamic and adaptive approach than traditional routing protocols. One of the primary reasons this approach was chosen over others is its ability to handle link failures and congestion efficiently without necessitating a complete restart of the route discovery process, which is a common drawback in traditional MANET routing protocols. Here’s a comprehensive explanation of how these design choices contribute to the success of the protocol:

• Handling Link Failures with Partial Path Recovery: Traditional routing protocols typically rely on the discovery of the shortest path between a source and a destination, which is efficient under ideal conditions but problematic when link failures occur due to node mobility, bandwidth limitations, or energy depletion. In these situations, the source node often needs to restart the entire route discovery process, resulting in significant delays, packet retransmissions, and performance degradation. In contrast, LBCAR takes a more proactive approach. When a link failure occurs, rather than initiating an entirely new route discovery process, the algorithm temporarily halts packet transmission and waits for a partial path to be re-established. This reduces the overhead and delays associated with frequent route rediscovery, allowing the source node to quickly resume transmission once an alternative path is found. This design decision contributes to higher data delivery rates and reduces packet loss, which is particularly important in networks with high mobility or frequent disconnections.

• Congestion Management with Adaptive Queuing: In LBCAR, congestion is managed effectively by utilizing the limited queue available at each node in the transmission layer. Unlike traditional routing protocols that may struggle with managing high traffic loads or congestion, LBCAR introduces congestion awareness by allowing nodes to temporarily store packets in their queue while searching for an alternate route during congestion. This adaptive queuing mechanism helps manage temporary traffic spikes without overwhelming the network, preventing congestion from spreading and affecting overall performance. This approach ensures that the network remains balanced, even during periods of high traffic, by distributing the load dynamically. As a result, queue management at the node level contributes to smoother data flow, reducing delays and improving overall network efficiency.

• Avoidance of Immediate Route Discovery Restarts: Traditional protocols require a full restart of the route discovery process whenever a connection failure occurs, even if the shortest path is no longer available. This leads to significant overhead, as the source node must re-broadcast route requests and wait for replies, which in turn increases delays and degrades performance, especially in scenarios with frequent disconnections or node mobility. LBCAR mitigates this by pausing packet transmission and waiting for an alternate or partial route to be found before attempting a full route discovery. This design choice reduces unnecessary route discovery cycles, ensuring that data transmission can resume more quickly after a failure. Additionally, by utilizing temporary paths, LBCAR minimizes the retransmission of packets, which conserves bandwidth and energy, ultimately improving the network lifetime.

• Load Balancing for Improved Resource Utilization: Another critical advantage of LBCAR is its load-balancing mechanism, which distributes traffic across multiple nodes to prevent any single node from becoming a bottleneck. Traditional routing protocols, especially those that prioritize shortest-path routes, often overburden certain nodes, leading to congestion and faster energy depletion in those nodes. By taking both congestion and node energy levels into account when making routing decisions, LBCAR balances the load more effectively. This prevents individual nodes from becoming overwhelmed and helps prolong the lifetime of the network by ensuring that energy resources are used more evenly across the entire network.

• Energy Efficiency and Network Longevity: In mobile ad-hoc networks, energy efficiency is a major concern, particularly for portable nodes with limited battery life. LBCAR addresses this by incorporating energy-aware routing decisions. Instead of focusing solely on the shortest path, LBCAR selects routes based on the energy availability of nodes, ensuring that low-energy nodes are not overburdened and can continue functioning longer. This helps extend the operational lifetime of the entire network.

• Contribution to Protocol Success: The combination of these design choices—handling link failures through partial path recovery, adaptive queuing for congestion management, and load balancing for efficient resource utilization—makes LBCAR more resilient, responsive, and efficient in high-traffic, high-mobility environments. By reducing the need for frequent route discovery and managing congestion adaptively, LBCAR ensures higher data throughput, lower latency, and more balanced energy consumption across the network. These features make LBCAR particularly suited for large-scale, energy- constrained networks such as wireless sensor networks and mobile ad-hoc networks (MANETs), where traditional approaches often fall short due to their reliance on fixed route discovery processes and their inability to adapt to dynamic network conditions effectively.

The CALB algorithm manages message broadcasts and route discovery in a network. A source node s begins by broadcasting a Route Request (RREQ) and waits for an acknowledgment. If it receives a Route Reply (RREP), it starts transmitting data; if it gets a Route Discovery Negative (RDN), it stops and pauses for an alternative path. If a Route Update Needed (RUN) message is received, the node re-initiates the route discovery process, while a Route Service Normal (RSN) message signals that the route is valid, allowing the node to resume transmission. If none of these messages arrive, the node stays on hold awaiting further instructions.

This paper investigated the packet-sending issue of route estimation of the LBCAR protocol is utilized and it does not demonstrate the ideal outcome. So we are changing the default estimation of protocol by utilizing the enhancement procedure and discovering the ideal consequence of sending packet.

Problem statement:

• Simulation of basic LBCAR protocol with standard value.

• Optimization system to consequently tune the LBCAR design.

• Performance assessment of streamlined LBCAR Protocol

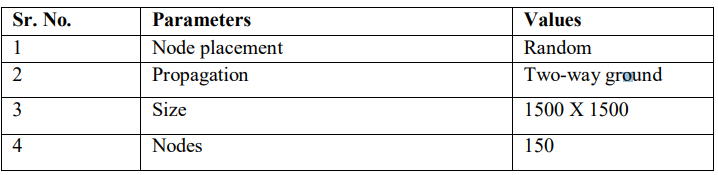

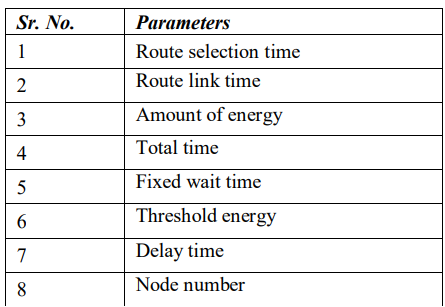

4. SIMULATION FRAMEWORK

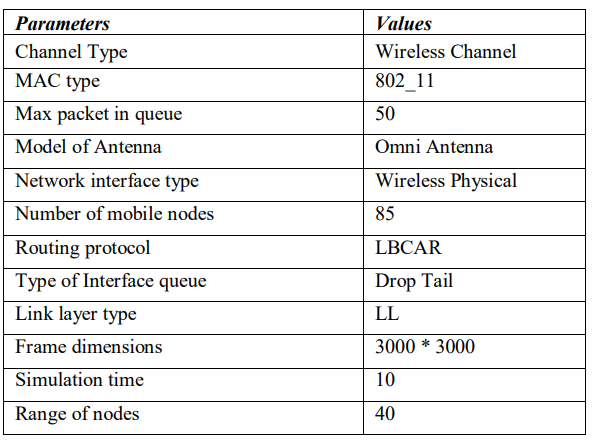

In the proposed scenario, the experimental network setup utilizes omnidirectional antennas for each mobile node, employing a Two-Ray ground radio propagation model. The simulation framework for this study is developed based on the configuration of a dynamic network with a set of three parameters for performance measurement using network simulation software Network Simulator Version 2. The experimental setup is shown in Table I and simulation parameters are given in Table II. The Simulation design with 50 nodes is shown in fig. 2. The communication among the network is shown through the transmission of 100 to 1,000 data packets with a minimum speed of 4 packets each second to 25-100 packets each second.

Table I Experimental Setup

4.1. Experimental Design

Based on the described technique, we will incorporate the waypoint technique along with load balancing to optimize and enhance the derived parameters. A parallel event-driven testing framework, NS2, was used in conjunction with VMware to obtain the expected results of the protocols. The simulation tests were continuously conducted on a computer running NS2 within a VMware virtual machine, allowing us to assess the effects of simulation speed and framework configuration on the experimental outcomes. The implementation follows a systematic design, with the modules outlined below:

Module 1

• Base files will be created for MANET design and transfer of packets.

Module-2

• Topology of MANET with a particular number of nodes deployed in any dynamic network

• Transmission of packets among the nodes by using existing two protocols AOMDV-ER AND AOMDV.

• Values of parameters such as delay time, throughput, and energy variance are calculated according to given optimization parameters for two existing protocols.

Module-3

• Topology of MANET with a particular number of nodes deployed in any dynamic network

• Transmission of packets among the nodes by using the proposed LBCAR protocol (which is developed as a hybrid technique cum protocol using C++ in the NS2 package).

• Values of parameters such as delay time, throughput and energy variance are calculated according to given optimization parameters (using the proposed routing protocol).

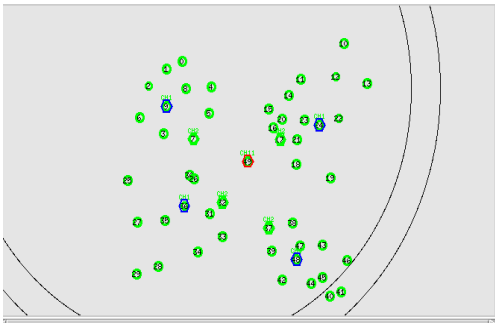

Simulation design: With 50 nodes

Fig. 2: Simulation design with 50 nodes

Table II Simulation Parameters

4.2. Performance Metrics

The performance metrics in the proposed work such as delay time, throughput and energy variance have been estimated for our proposed LBCAR algorithm and compared with AOMDV and AOMDV-ER. The experimental parameters are to be calculated to increase network life and network effectiveness.

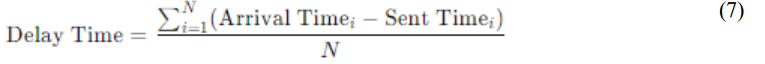

• Delay time: It is a measurement of time consumed by every packet transmission from the sender to receiver. The one of the indications of network congestion is higher end-to- end delay.

Arrival Time: When the packet reaches the receiver.

Sent Time: When the packet leaves the sender.

N: Total number of packets sent successfully

• Throughput: Number of bytes received of data × 8 / Simulation time × 1,000 kbp (8) Total Bytes Received: Total data received (in bytes).

Simulation Time: Total time of the simulation (in seconds).

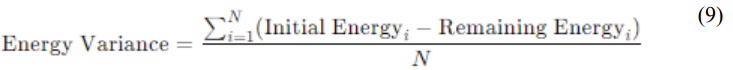

• Energy Variance: It is the measurement of total energy utilization by the nodes reduced by change in the energy after a fixed interval of time.

Initial Energy: Energy of the node before the process starts.

Remaining Energy: Energy left in the node after a certain time.

N: Total number of nodes in the network.

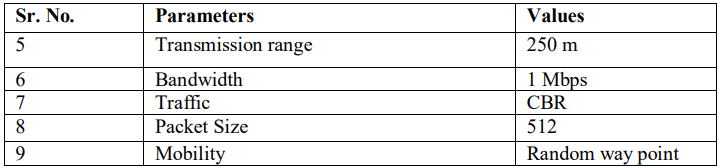

Table III Parameters for Node Processing

To cover a more extensive region for message gathering, some neighboring vehicles can serve as potential forwarders, and each forwarder needs to sit tight for a specific timeframe (i.e., dispute time) before sending the message.

5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

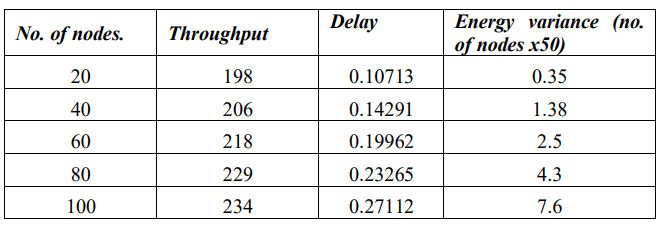

Simulation results have demonstrated the efficiency of the proposed LBCAR protocol for MANET. We measured the data delivery performance under three major parameters by varying the number of nodes for three different protocols. The results shown are as below

Input nodes= 100

Table IV Performance results of proposed protocol LBCAR

Table IV shows the results of the proposed protocol LBCAR for parameters delay, throughput, and energy variance. It described that as the number of nodes upsurges the values of all parameters improvised but in a low pace.

Comparison Results:

The comparison results of two protocols as AOMDV-ER AND AOMDV with our proposed protocol LBCAR for three parameters as delay, throughput and energy variance are presented below graphs as well as in tabular form as follows.

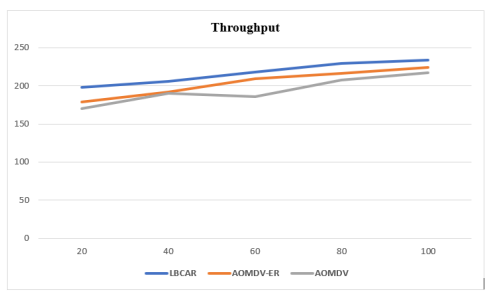

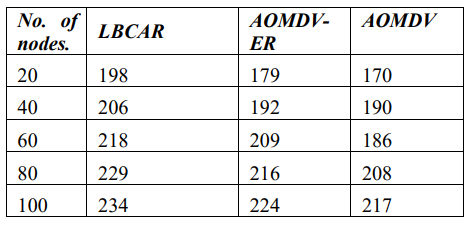

Fig. 3: Comparison graph of simulation for throughput among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER AND LBCAR routing protocols

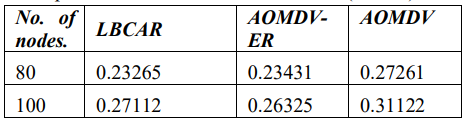

In fig.3 It is the amount of data successfully received at the destination over a given period (measured in kbps). Higher throughput indicates better data transmission performance. As the number of nodes increases, throughput improves for all three protocols. However, LBCAR consistently achieves higher throughput compared to AOMDV-ER and AOMDV across all scenarios. LBCAR’s load-balancing and congestion-aware mechanisms help avoid bottlenecks in the network. By distributing the load evenly among multiple nodes, it ensures smoother data transmission and reduces packet loss, resulting in higher throughput. AOMDV-ER, with its energy-aware enhancements, performs slightly better than AOMDV. However, it still lags behind LBCAR, indicating that while energy-awareness helps improve throughput, load balancing has a greater impact on transmission efficiency.

Table V Comparison results of simulation for Throughput among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER, LBCAR routing protocols

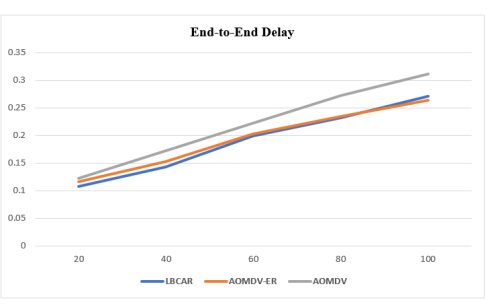

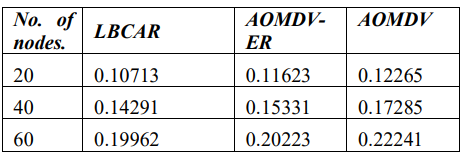

Fig. 4: Comparison graph of simulation for End-to-end delay among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER AND LBCAR routing protocols

In fig 4. Delay increases as the number of nodes grows, which is typical in networks due to higher communication overhead and congestion. However, LBCAR maintains lower end-to-end delays than both AOMDV-ER and AOMDV at all node counts. LBCAR’s congestion-aware routing reduces the probability of packets being queued or dropped, which helps maintain a smooth flow of traffic even as the network scales. Additionally, efficient load balancing reduces delays by preventing overburdening specific nodes. AOMDV-ER performs better than AOMDV, likely because its energy-aware mechanisms indirectly reduce congestion by selecting more energy-efficient paths, which avoids overloaded routes.

Table VI Comparison results of simulation for End-to-end Delay among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER, LBCAR routing protocols

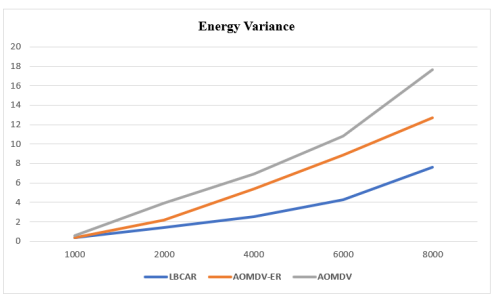

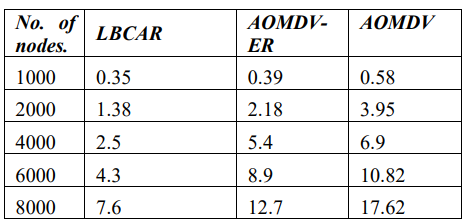

Fig. 5: : Comparison graph of simulation for energy variance among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER AND LBCAR routing protocols

In fig 5. As the number of nodes increases, energy variance rises for all protocols, but LBCAR consistently has the lowest variance. AOMDV shows the highest energy variance, indicating inefficient energy utilization. LBCAR’s energy-aware routing mechanism ensures that energy consumption is evenly distributed among nodes, preventing certain nodes from being overused. This extends the overall network lifetime and reduces the likelihood of node failures. AOMDV- ER improves upon AOMDV by incorporating some energy-efficient strategies, but it still shows a higher variance than LBCAR. This suggests that LBCAR’s combination of energy-awareness with load balancing is more effective at distributing energy consumption.

Table VII Comparison results of simulation for Energy variance among AOMDV, AOMDV-ER, LBCAR routing protocols

From the results shown in fig. 3, fig.4 and fig.5 we see that the proposed protocols show better results in comparison to other two existing protocols in the aspect of all three simulation parameters. From table V, table VI and table VII following results are drawn from the proposed work:

The comparison of AOMDV, AOMDV-ER, and LBCAR based on throughput, delay, and energy variance reveals the following key insights: LBCAR achieves the highest throughput, showing better data transmission performance. The load-balancing strategy in LBCAR ensures efficient data routing, reducing packet loss and congestion. LBCAR shows the lowest end-to-end delay, making it ideal for real-time communication scenarios. Its congestion-aware routing ensures fast delivery times, even as the network scales. LBCAR demonstrates the lowest energy variance, meaning energy consumption is evenly distributed across nodes. This helps prevent node failures and extends the overall network lifetime, which is crucial for energy-constrained networks.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In the LBCAR proposed algorithm, the idea of congestion adaptiveness and load balancing is combined effectively. Through this technique, one can adaptively change the probability of sending the messages as directed by the dispersion and in route discovery time load status of nodes. results drawn from the simulation process are compared with AOMDV-ER and original AOMDV. The proposed work is comparatively significantly enhanced the throughput and reduced the delay and energy variance with increasing the network lifetime and balancing the load in the network. Future research on the LBCAR algorithm should focus on optimizing its performance for larger and heterogeneous networks, exploring the integration of machine learning for real-time traffic prediction, and evaluating its effectiveness in dynamic and mobile environments like MANETs and VANETs. Additionally, assessing its scalability in IoT and smart city networks is essential to ensure its broader applicability. Security and robustness should also be addressed to protect against malicious nodes and attacks. However, the current study has some limitations: it is based on simulations that may not reflect real-world complexities, scalability issues may arise in larger networks, and there has been limited evaluation in highly mobile environments. The assumption of uniform node characteristics may not hold in heterogeneous networks, and security vulnerabilities, such as denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, have not been considered.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

[1] Patra, S. P. Mohanty, and R. K. Biswal, “Load-Balanced Routing for Congestion Mitigation in IoT Networks Using Fuzzy Logic,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 4258-4268, May 2020, doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.2974820.

[2] Sharma, P. Patil, and R. Joshi, “Enhanced Load Balancing Routing Protocol for Congestion Control in MANET,” IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 215-226, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TMC.2019.2954823.

[3] Alba, E., et al.: A Cellular MOGA for Optimal Broadcasting Strategy in Metropolitan MANETs. Computer Communications 30(4), 685–697 (2007)

[4] P. Rimal, D. P. Van, and M. Maier, “Load-Balanced Congestion Control in Fog-Cloud Computing Networks,” IEEE Trans. Network Service Manag., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 219-230, Mar. 2019, doi: 10.1109/TNSM.2018.2877884.

[5] Binitha S, S Siva Sathya. A Survey of Bio inspired Optimization Algorithms. International Journal of Soft Computing and Engineering (IJSCE), May 2012, ISSN: 2231-2307, Volume-2, I (2).

[6] B. Johnson and S. PalChaudhuri, “Power mode scheduling for Ad Hoc networks,” in Proc. International Conference on Network Protocols, 2008, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 192-193.

[7] Koutsonikolas, C.-C. Wang, and Y. C. Hu, “CCACK: Efficient Network Coding Based Opportunistic Routing through Cumulative Coded Acknowledgments,” in Proceedings of the 29th IEEE International Conference on Computer Communication (INFOCOM). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE Press, 2010, pp. 2919–2927.

[8] Yuan, X. Liu, and Y. Chen, “Energy-Efficient Load-Balanced Routing for Congestion Control in MANETs,” IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol., vol. 69, no. 8, pp. 8204-8215, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TVT.2020.3000121.

[9] Falko Dressler, Ozgur B. Akan. Bio-Inspired Networking: From Theory to Practice. IEEE Communications Magazine, November 2010.

[10] Cervera, M. Barbeau, J. Garcia-Alfaro, and E. Kranakis, “A multipath routing strategy to prevent flooding disruption attacks in link state routing protocols for manets,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 744–755, 2013.

[11] Du, W. Chen, and Y. Zhang, “Adaptive Load-Balanced Routing for Congestion Control in VANETs,” IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 1558-1568, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TITS.2019.2912733.

[12] T. Tran, D. L. Nguyen, and M. S. Kim, “Congestion Control and Load Balancing in Smart Grid Networks Using SDN,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 152233-152245, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3018422.

[13] Haseeb K, Abbas N, Saleem MQ, Sheta OE, Awan K, et al. (2019) Correction: RCER: Reliable Cluster-based Energy-aware Routing protocol for heterogeneous Wireless Sensor Networks. PLOS ONE 14(10): e0224319.

[14] Lin, X. Wang, and Q. Zhang, “Load-Aware Routing and Congestion Control in Wireless Mesh Networks,” IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput., vol. 19, no. 9, pp. 2142-2153, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TMC.2020.2969647.

[15] Zhang, G. Tan, and W. Fan, “Load-Balanced Routing Algorithm for Congestion Mitigation in IoT Networks,” IEEE Internet Things J., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 3271-3282, Apr. 2020, doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.2964820.

[16] Jadoon R, Zhou W, Jadoon W, Ahmed Khan. RARZ: Ring-Zone Based Routing Protocol for Wireless Sensor Networks. Applied Sciences 8: 1023, 2018.

[17] Ji X, Wang A, Li C, Ma C, Peng Y. ANCR—An Adaptive Network Coding Routing Scheme for WSNs with Different-Success-Rate Links. Applied Sciences 7: 809, 2017.

[18] Singh, R. Kumar, and S. Jain, “Dynamic Load-Balanced Routing Protocol for Congestion Control in MANETs,” IEEE Syst. J., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 294-305, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1109/JSYST.2019.2920459.

[19] Miao, F. Ren, C. Lin, and A. Luo. A-ADHOC: An adaptive real time distributed MAC protocol for vehicular ad hoc networks. Proc. 4th China COM, Xi’an, China. Aug. 2009, pp. 1–6.

[20] Reddeppa Reddy and S. V. Raghavan, “Smort: scalable multipath on-demand routing for mobile ad hoc networks,” Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 162–188, 2007.

[21] L. Zhu, Z. Gao, and X. Li, “Load-Aware Congestion Control in Data Center Networks Using Machine Learning,” IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 763-774, Apr. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TCC.2020.2970851.

[22] Gawas and M. M. Gawas, “Efficient multi objective cross layer approach for 802.11e over MANETs,” in Proceeings of the 2018 14th International Wireless Communications Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), pp. 582–587, Tangier, Morocco, June 2018.

[23] M. A. Gawas, L. J. Gudino, and K. R. Anupama, “Cross layer congestion aware multi rate multi path routing protocol for ad hoc network,” in Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICSC), pp. 88–93, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, March 2015.

[24] M. K. Khan and I. Ahmed, “A Novel Load-Aware Routing Protocol for Congestion Control in Wireless Mesh Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 159173-159184, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3018674.

[25] Musaddiq, A., Zikria, Y.B., Zulqarnain et al. Routing protocol for Low-Power and Lossy Networks for heterogeneous traffic network. J Wireless Com Network 2020, 21,2020.

[26] Liu, Y. Zhang, and G. Cao, “Deep Learning-Based Load-Balanced Routing and Congestion Control for SDN,” IEEE Trans. Network Service Manag., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 1234-1245, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TNSM.2021.3065034.

[27] R. Reddy, B. K. Mohanty, and S. K. Tripathy, “Load-Balanced Congestion Control in Mobile Ad Hoc Networks Using Fuzzy Logic,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 118942-118951, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2934245.

[28] Rashmi Patil and Rekha Patil,” Cross Layer Based Congestion Free Route Selection in Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks”, International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC) Vol.14, No.4, pp 81-98, July 2022, DOI: 10.5121/ijcnc.2022.14405

[29] Gupta, N. Suri, and D. S. Kim, “Load Balancing and Congestion Control Using Deep Reinforcement Learning in SDN,” IEEE J. Select. Areas Commun., vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 1455-1465, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1109/JSAC.2020.2998502.

[30] Tafazolli and L. Hanzo, “A survey of qos routing solutions for mobile ad hoc networks,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 50–70, 2007.

[31] Arzil, M. H. Aghdam, and M. A. J. Jamali. Adaptive routing protocol for vanets in city environments uses real-time traffic information. Proc. ICINA, Oct. 2010, vol. 2, pp. 132–136.

[32] G.S.Tomar, L. Shrivastava and S.S.Bhadauria,” Load Balanced Congestion Adaptive Routing for Randomly Distributed Mobile Adhoc Networks,” Wireless Pers Commun 2014, DOI 10.1007/s11277-014-1663-9

[33] K. Das, S. Roy, and P. Dutta, “Congestion-Control Aware Load-Balanced Routing in Wireless Sensor Networks,” IEEE Sens. Lett., vol. 3, no. 8, pp. 1-4, Aug. 2019, doi: 10.1109/LSENS.2019.2927834.

[34] S. Lee, K. Kim, and J. Lee, “Hybrid Congestion Control Mechanism in SDN-Enabled Networks,” IEEE Commun. Lett., vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 1133-1136, May 2017, doi: 10.1109/LCOMM.2017.2655523.

[35] S. Taghizadeh, H. Bobarshad and H. Elbiaze, “CLRPL: Context-Aware and Load Balancing RPL for Iot Networks Under Heavy and Highly Dynamic Load,” IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 23277–23291, Apr. 2018.

[36] Valarmathi, A., & Chandrasekaran, R. M, (2010, October). Congestion aware and adaptive dynamic source routing algorithm with load-balancing in MANETs. International Journal of Computer Applications (0975–8887), 8(5),1–4

[37] X. Chen, H. M. Jones, and A. D. S. Jayalath, “Congestion-aware routing protocol for mobile ad hoc networks,” in Proceedings of the IEEE 66th Vehicular Technology Conference, pp. 21–25, Baltimore, MD, USA, October 2007.

[38] X. Li, Y. Lin, and Q. Wang, “Load-Balanced and Congestion-Aware Routing in Hybrid Wireless Networks,” IEEE Trans. Commun., vol. 68, no. 11, pp. 6758-6769, Nov. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TCOMM.2020.3008921.

[39] X. Wu, H. Wang, and S. Li, “Load-Balanced Multipath Routing for Congestion Control in Wireless Ad Hoc Networks,” IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun., vol. 18, no. 12, pp. 5723-5733, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1109/TWC.2019.2937593.

[40] Y. He, J. Wang, and L. Ma, “Congestion Control Algorithm for Industrial Wireless Networks Based on Load Balancing,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat., vol. 14, no. 9, pp. 4100-4109, Sep. 2018, doi: 10.1109/TII.2018.2808927.

[41] Y. Zhou, X. Yang, and H. Yu, “Adaptive Congestion Control Protocol for Wireless Sensor Networks,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 2539-2548, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2018.2805752.

AUTHORS

Dr.Jogendra Kumar is working as Assistant Professor, Faculty of Computer Science and Engineering Department, G.B.Pant Institute of Engineering and Technology Pauri Garhwal Uttarakhand-246194. He has fifteen years of teaching experience in Engineering, UG and PG level. Her research interest includes Wireless Networks, IoT, Block Chain Technology, Big Data Analytics, Machine Learning and WSN. Two Ph.D scholars were pursuing their research under his guidance. He is also a International Scientific Committee member for Researchers in various universities. He has received two awards. He has published many research papers, books, book chapters in SCI, WoS, IEEE, SCOPUS journals. He also published many patents in IPR. He serves as Editor in Book Chapters, Editorial Board Member and Reviewer in various International Journals. He is an active member in Professional Bodies like ISTE, IAENG (USA) and IACSIT.