A SYSTEMATIC RISK ASSESSMENT APPROACH FORSECURING THE SMART IRRIGATION SYSTEMS

Anees Ara1, Maya Emar2, Renad Mahmoud2, Noaf Alarifi2, Leen Alghamdi2, and

Shoug Alotaibi2

1Computer Science Department, College of Computer Science, Prince Sultan University,

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2 College of Computer Science, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

The smart irrigation system represents an innovative approach to optimize water usage in agricultural and

landscaping practices. The integration of cutting-edge technologies, including sensors, actuators, and data analysis, empowers this system to provide accurate monitoring and control of irrigation processes by leveraging real-time environmental conditions. The main objective of a smart irrigation system is to optimize water efficiency, minimize expenses, and foster the adoption of sustainable water management methods. This paper conducts a systematic risk assessment by exploring the key components/assets and their functionalities in the smart irrigation system. The crucial role of sensors in gathering data on soil moisture, weather patterns, and plant well-being is emphasized in this system. These sensors enable intelligent decision-making in irrigation scheduling and water distribution, leading to enhanced water efficiency and sustainable water management practices. Actuators enable automated control of irrigation devices, ensuring precise and targeted water delivery to plants. Additionally, the paper addresses the potential threat and vulnerabilities associated with smart irrigation systems. It discusses limitations of the system, such as power constraints and computational capabilities, and calculates the potential security risks. The paper suggests possible risk treatment methods for effective secure system operation. In conclusion, the paper emphasizes the significant benefits of implementing smart irrigation systems, including improved water conservation, increased crop yield, and reduced environmental impact. Additionally, based on the security analysis conducted, the paper recommends the implementation of countermeasures and security approaches to address vulnerabilities and ensure the integrity and reliability of the system. By incorporating these measures, smart irrigation technology can revolutionize water management practices in agriculture, promoting sustainability, resource efficiency, and safeguarding against potential security threats.

KEYWORDS

Smart irrigation system, Cybersecurity, Risk Assessment, Vulnerability Identification, Risk Management,

Soil sensor, Water & humidity sensors, DC water pump, Water management, IoT, Sustainable agriculture

1.INTRODUCTION

A Smart irrigation system is an application of cyber-physical systems that optimizes the process

of watering plants. It basically monitors soil moisture using sensors then it waters the plants

whenever needed, so that it can optimize the usage of water resources [1]. Smart irrigation

systems would be well suited for cities with hot, arid climates such as Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

especially as there are some challenges in optimizing water [2]. The 2030 vision aims for

sustainability and economic diversification which indicates the need for smart irrigation systems

[3]. Currently, there are several risks associated with smart irrigation systems such as cost,

reliability and robustness, environmental issues, single point of failure, lack of knowledge and

training, and data privacy and security. Some of these risks include, firstly, some farmers can’t

afford to have smart irrigation systems or their maintenance costs. Secondly, smart irrigation

systems depend heavily on technology so if there is a failure in the software or hardware

malfunction it will lead to incorrect decisions. Thirdly, as stated earlier, smart irrigation systems

depend heavily on technology. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that other

environmental factors, such as soil type and quality, can significantly impact the irrigation

process. Moreover, farmers may be living a simple life having the minimum knowledge in the

technology field, so they lack the knowledge and training [4]. Lastly, without applying

appropriate security measures this system can be compromised and vulnerable to other threats.

Smart irrigation systems offer several contributions to agriculture. Firstly, the enhancement of

water efficiency is achieved through the utilization of sensors and data analysis, enabling the

optimization of irrigation scheduling based on factors such as soil moisture, weather conditions,

and plant water requirements. This leads to significant water savings and conservation of this

valuable resource. Secondly, these systems contribute to the improvement of crop yield and

quality by delivering the precise amount of water at the optimal timing, fostering robust plant

growth and facilitating efficient nutrient uptake. Thirdly, smart irrigation systems contribute to

resource conservation by reducing water waste and minimizing runoff, particularly in regions

facing water scarcity or drought conditions. Additionally, they save farmers time and labor by

automating the irrigation process, allowing them to focus on other important farming tasks. The

data-driven nature of these systems empowers farmers to make informed decisions based on realtime information, leading to improved crop management and optimized resource allocation.

Lastly, the scalability and adaptability of smart irrigation systems make them suitable for various

farm sizes and crop types, ensuring their applicability in diverse agricultural operations.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- This paper conducts an in-depth literature review by analysing existing research articles

to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the art. - This paper proposes a systematic approach for security risk assessment that includes the

crucial steps such as asset prioritization, malicious actors and threat identification,

vulnerability Identification, risk estimation, risk management Strategies. - This paper proposes a secure CPS architecture design for smart irrigation system that

includes the phases of hardware acquisition, circuit design and assembly, software

development, calibration and optimization. - This paper conducts detailed security analysis on the proposed system to know the asset

to threat mapping and discover the known vulnerabilities. This paper suggests a

summarized list of mitigations and countermeasures to enhance security of these systems.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 1 talks about the project description, scope, and

importance of the smart irrigation system. In Section 2, this paper examines the relevant works

concerning the security of smart irrigation systems and explores the potential consequences that

may arise if these systems are compromised. Section 3 proposes an overall assessment of security

risk. Section 4 discusses the architecture overview of the proposed model and security model.

Section 5 summarizes the analysis of selection along with security analysis results. Section 6

concludes the whole paper.

2.RELATED WORKS

Agriculture automation is a serious topic because it is a vital industry and the cornerstone of the

economy [4]. Obaideen et al [4] stated that water conservation and automated control are two of

the many advantages of smart irrigation systems. Nonetheless, similar to interconnected systems,

smart irrigation systems are not immune to security risks, including cyber threats such as remote

unauthorized access and physical security vulnerabilities. For example, water management plays

a crucial role in irrigation, the presence of vulnerabilities in smart irrigation systems can lead to

unauthorized access and control by cybercriminals. These malicious actors may exploit weak

passwords, unpatched software, or insecure network connections as entry points. Upon successful

infiltration, malicious actors have the capability to manipulate irrigation schedules, modify

system settings, and disrupt the overall operation of the system [4]. So, over-irrigation and poor

water use can cause groundwater depletion, reducing water levels and producing ecological

imbalances. Implementing effective water management practices, such as precision irrigation

techniques and the adoption of water-efficient technologies, plays a vital role in reducing

environmental impacts and fostering sustainable agriculture. Therefore, any unauthorized

modifications to system settings and data can have detrimental consequences. It is imperative to

ensure that the system is closely monitored by authorized personnel to mitigate such risks. In

addition, the physical components of these systems, including controllers and sensors, can be

attractive targets for theft. When these components are stolen, it can lead to system malfunctions,

resulting in water wastage, potential crop damage, and financial losses for the operator.

Moreover, the Physical Damage from Natural Catastrophes because Smart Irrigation Systems are

often placed in outdoor locations; they are vulnerable to natural catastrophes such as hurricanes,

floods, and earthquakes. These incidents can cause physical damage to the infrastructure of the

system, rendering it unworkable and necessitating costly repairs or replacements [4].

A study conducted by Rad et al[5] showed that Smart Irrigation Systems protect a variety of data

types, including operational logs, personal identifiable information (PII), and user credentials.

Smart irrigation systems frequently contain user accounts or administrative interfaces that require

authentication. To prevent unauthorized access to the system and its settings, smart irrigation

systems employ measures to protect user credentials, including usernames and passwords.

Additionally, authors suggested that these systems also prioritize the security of sensor data,

which encompasses information gathered from various sensors such as soil moisture sensors,

weather sensors, and flow meters [5]. Safeguarding this data is critical for making correct

irrigation scheduling and water management decisions [5]. Sontowski et al. [9] discussed that the

cyber-attacks on smart farming infrastructure may result in unsafe and unproductive farming

environments. Their study explained different types of network attacks on smart farms such as

Password Cracking, Evil Twin Access Points, Key Reinstallation Attacks, Wi-Fi

deauthentication, and ARP and DNS Spoofing Attacks. Their paper focused more on

deauthentication attacks on smart farms that can disarray sensor data, crops will be irrigated with

more or much less water than they need, or it is possible to control agricultural drones responsible

for spraying pesticides or fertilizers in unwanted quantities, affecting crops, animals, and even

humans. If it occurs in a wider place, it will also lead to huge financial losses. One of the

techniques suggested to avoid this kind of attack is enabling IEEE 802.11w-2009 due to the

encryption it has [9]. Darshna et al [12] discusses the process of irrigation and watering plants

with minimal manual interventions by building a prototype using the necessary tools [12]. If the

soil is wet, water pumping will be stopped, but if it is dry, water will be pumped. Although the

prototype was successfully tested in a garden setting, the researchers have future plans to

incorporate a Web-scraper that can utilize weather predictions to adjust the irrigation of plants or

crops accordingly [1]. Similarly, Bwambaleet al in [10] conducted a study on smart irrigation

monitoring and control strategies to improve water use efficiency in precision agriculture. The

findings of the study indicated the necessity for additional research to bridge existing gaps

concerning the monitoring sensors for weather, plants, and soil [10]. Moreover, Rettori et al in

[11] explained that smart systems have four layers: perception layer, network layer, edge, and

application; each layer has different types of attack. Also, they stated some of the possible safety

resources are IDS, Cryptography, Access Control, Firewall, and Anti-virus. Although smart

irrigation has begun to spread, it is still a topic that needs research in many areas, including

security [11]. Akter et al. [12] discussed about the necessary equipment and methodologies for

implementing smart irrigation systems were outlined. This includes the utilization of an Arduino

UNO board as a microcontroller, a Soil Moisture Sensor for measuring soil water content, a

Relay as an electrical switch for water control, a Water Pump for water supply, Jump Wire for

circuit connections, and the Arduino IDE Software for programming and uploading code to the

Arduino board.

Even though the smart irrigation system is not new, our project introduces a combination of

components and functionality that differs from others in multiple criteria such as: Arduino

Integration: Other irrigation systems use special hardware and other special controllers to

implement this system, but we are using Arduino as a microcontroller board that allows us to be

cost-efficient [12]. Soil Moisture Sensor: Another novel aspect of our system is the soil moisture

sensor, which determines when to stop watering to optimize water usage. Unlike others, they use

timers to irrigate. Overwatering Prevention: Another novel aspect of our system is preventing

overwatering. Soil sensors will sense and determine when to turn on/off the water pump. The

smart irrigation system operates by activating the water pump when the soil is detected to be dry

and deactivating it when the soil is determined to be wet. This will prevent overwatering issues in

other irrigation systems. Scheduling Irrigation: Our system stands out from the competition

because it uses a soil mature sensor instead of a traditional irrigation system’s timer or schedulers.

Cost Reduction: When comparing the hardware and specialized controllers used by the smart

irrigation system to those used by the Arduino, the low price makes it the clear winner.

Environmental Sensibility: Our system can ensure Water Conservation and Improve Soil Health

by providing water only when the moisture level drops below a certain threshold [6-7]. Security:

Our system implements secure authentication mechanisms (username/password authentication)

and encryption algorithms to ensure secure communication between the components.

3.PROPOSED SYSTEMATIC RISK ASSESSMENT FOR SMART IRRIGATION

SYSTEMS

A Smart irrigation system emerged to enhance plant irrigation. This project can be used in

residential gardens, agricultural fields, parks, public spaces, and farmers. The purpose is to

effectively manage water resources, increase agricultural production, and simplify irrigation

management. However, this project is a prototype representing a small-scale model by using

sensors and other types of equipment such as Arduino Uno, soil moisture sensor, relay, DC water

pump, 9V battery, connecting cable, and male-to-male jumper wires. Moreover, farmers,

agricultural communities, and landscapers who want to enhance their irrigation methods and save

water resources are the primary users of the Smart Irrigation System. The business objectives

include water conservation, increased agricultural productivity, cost savings, time efficiency, and

scalability. The project initiates with a comprehensive risk assessment, encompassing the

identification and prioritization of assets, identification of malicious actors and threats,

identification of vulnerabilities, quantification of vulnerabilities, and estimation and calculation

of risks. The outcomes of the risk assessment will inform the design of a secure Cyber-Physical

System (CPS) prototype, followed by a thorough CPS security analysis.

3.1. Assets Identification and Prioritization

Asset Identification starts by identifying the different assets that help in developing the smart

irrigation system and then prioritizing them by considering their criticality to the system. Assets

can be tangible and intangible. Tangible assets such as sensors, controllers, actuators, DC Water

Pumps, and communication networks; whereas the intangible assets are the Central Management

System (CMS) and reputation. Table 1 describes the list of possible assets identified and

prioritized in smart irrigation systems.

Table 1. Assets Identification and Prioritization Table

The ranking/prioritization is based on the security importance of the possible impact of a security

breach or compromise on the entire system’s integrity, data privacy, and dependability as shown

in Table 1. As a result of technological advancements and evolving environmental and societal

conditions, the assets of a smart irrigation system have the potential to undergo modifications in

the future. These modifications may include the addition of new assets or the enhancement of

existing ones to align with changing requirements. While some of these assets may become

obstacles or face changes.

Communication Networks: The deployment of 5G networks to improve the connection for

smart irrigation systems. On the other hand, the obstacle is keeping data transfer secure, because

it will be a constant problem.

Controllers: Controller algorithms could get more sophisticated, taking advantage of machine

learning and AI to make even more precise judgments. On the other hand, the integration with

many sensor types and data sources may grow complex, necessitating continual updates and

maintenance.

User Interface: An additional feature that can be incorporated into the smart irrigation system is

the integration of a mobile application, enabling users to remotely monitor and control the

system’s operations. These interfaces give real-time data on irrigation schedules, water use, and

sensor readings, allowing users to make changes and get messages or alarms enhancing the user

experience.

Leak Detection Systems: This will detect and locate irrigation system leaks. These systems can

identify anomalies in water flow and determine the site of leaks by using pressure sensors. Early

identification of leaks aids in limiting water loss and preventing system damage.

Additionally, the prioritization list needs to be reviewed periodically since it requires considering

their importance to the system’s operation, efficiency, and security. Prioritization will be changed

whenever the value of assets changes or new assets are added to the list to maintain security in

the system.

3.2. Malicious Actors and Threat Identification

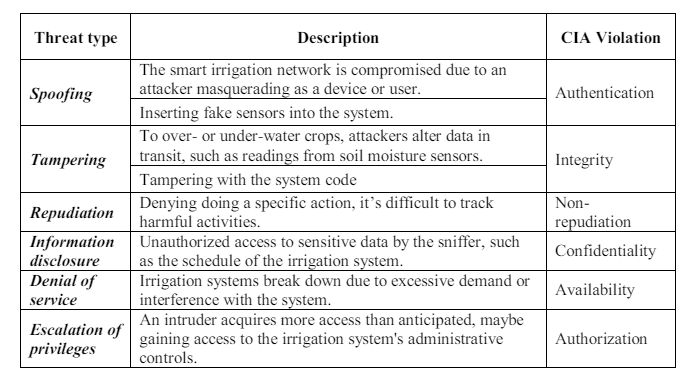

A smart irrigation system, like other CPS systems, has vulnerabilities and threats that allow

attackers with different motives to attack the system. These could be done through a human or

non-human basis as listed below:

3.2.1. Type of Attackers/ Human Based

Script Kiddies: Individuals with limited data who use pre-created items or programming to

exploit shortcomings in systems [18].

Hacktivists: Target systems for political or social objectives, for instance, battling water

wastage.

Insider: Misuser their privileges with authorized access to the smart irrigation system.

Competitors: Associations or components that increment from the mistake of a particular

smart irrigation system, wanting to stain its market reputation.

Hackers, possessing technical expertise, aim to illicitly infiltrate the system with the intention of

pilfering sensitive data.

3.2.2. Non-Human Based

Malware: Virus, worm, trojan, or ransomware that can infect different system assets.

Sensor failure: because of a hardware error or technical glitch.

Natural Disasters: they can impact the functionality of the system (physical and cyber

part).

3.2.3. Information Risk

Insufficient protection measures may expose various types of information to potential

unauthorized access by malicious actors. Here’s a breakdown of the types of information that

might be at risk:

Operational Data: Sensor Data, User Data, Personal Information, Usage Patterns, and

Credentials.

Network Data: Device Identifiers, Configuration Data, System Settings, and API Data.

Location Data: Geographic Coordinates.

Attackers utilize a broad range of techniques to discover and exploit software flaws; smart

irrigation systems are no exception. Before trying to breach a system, attackers would often

investigate it thoroughly [16]. After becoming familiar with the system, they begin searching for

vulnerabilities. After discovering a problem, the next step is to use it to one’s benefit. Once

inside, attackers may switch their focus to something else.

3.2.4. Threat Identification based on STRIDE Model

3.2.5. Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability (CIA) Triad

3.3. Vulnerability Identification and Quantization

Smart irrigation systems have much vulnerability that can be exploited such as weak credentials,

improper input validation, unpatched software, insecure communication channels, data privacy

concerns, and Denial of service (DOS) attacks. Discuss each of these in a bit of detail starting

with weak credentials which means having a weak username and password. Moving to improper

input validation which occurs when the software does not verify user input. Unpatched software

is software that has security issues that have not been fixed, updated, or patched. Lastly, insecure

communication channels refer to the methods of communicating or transmitting that are insecure.

Two vulnerabilities in the CPS domain that we will discuss in-depth are data privacy concerns

and denial of service (DOS) attacks; data privacy concerns are defined as improper handling of

user information that can lead to privacy violations if not handled properly whereas denial-ofservice attacks are used to flood the system with traffic to make the system unresponsive.

Commonly occurring vulnerabilities are related to the authentication and availability categories

of the CIA. Confidentiality refers to the protection of sensitive information from unauthorized

disclosure which leads to the disclosure of sensitive data, potentially compromising the privacy

of the data. Availability refers to the accessibility and usability of a system or service; that results

in disruptions or denial of service, rendering the system unavailable for its intended users.

The CIA triad can be considered as the main goal of cybersecurity, these two vulnerabilities

violate two of the CIA triad. To address privacy and security concerns, it is essential to uphold

confidentiality, ensuring that information is exclusively accessible to authorized individuals.

While denial-of-service attacks violate availability which means that information is available

whenever needed [23].

Privacy security concerns and Denial of service attacks are not specific to this domain nor

technology, they can be applied or exploited on several domains and technologies. As technology

advances and becomes widely utilized, the level of cyber-attacks will also increase. So, the level

of the discussed vulnerabilities will definitely increase with time. The impact of security, privacy

concerns, and violations brings significant safety risks that can lead to unsafe conditions in the

physical environment. The occurrence of vulnerabilities in the CPS domain has remained

relatively stable, with periodic discoveries of new vulnerabilities. However, this can affect the

growing complexity of CPS systems, which presents a larger scope for potential vulnerabilities

[24].

The impact of vulnerabilities in the CPS domain can be measured using various methods. One

commonly used approach is the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) system. CVE

serves as a reference or database that describes vulnerabilities published by organizations over

the years. Each vulnerability listed in the CVE includes a description and classification of the

vulnerability type. Additionally, vulnerabilities in the CVE are assigned scores that indicate their

severity. Another method to measure the impact of vulnerabilities is by the Common

Vulnerability Scoring System Calculator (CVSS), which is a framework designed to assess the

severity of vulnerabilities. The CVSS calculates an overall score based on three metric groups:

the Base, temporal, and environmental scores.

System assets may have multiple vulnerabilities such as the Central Management System (CMS)

which is a cyber asset within the system. In 2022 information leakage vulnerability was

discovered regarding CMS. The vulnerability was identified during an update of the SAP

Business Objects enterprise where authentication credentials were exposed in Sysmon event

loggers [25].

3.4. Risk Estimation and Calculation

In order to assess the risk in smart irrigation systems, we will use both qualitative and

quantitative approaches.

3.4.1. Qualitative Risk Analysis

The qualitative risk assessment method relies on observation and judgment to evaluate risk

levels. Risks are evaluated by assessing their likelihood and impact, leading to their

categorization as low, medium, or high. This approach is suitable for evaluating system

components that do not have a financial value. The NIST SP 800-30 [14] provides specific

definitions for the levels of impact and likelihood of risk as follows:

Impact: Very High, High, Moderate, Low, Very Low.

Likelihood: Very High, High, Moderate, Low, Very Low.

Hence, the risk level can be determined using the (Probability * Impact) matrix:

Table 4. Probability * Impact Matrix

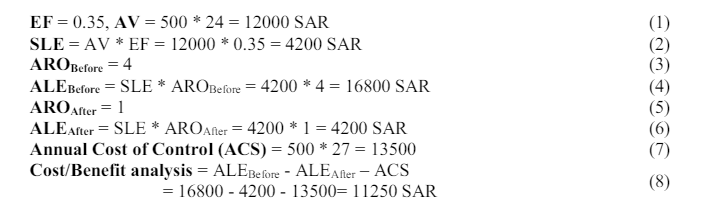

3.4.2. Quantitative Risk Analysis

The quantitative risk assessment is based on the assets’ values. It’s more realistic than the

qualitative risk assessment since it is based on real data, not on expert judgments [20]. In this

approach, some formulas are used to calculate the risk value based on assets’ value [19-21].

We decided to calculate the expected loss in a year called Annual loss expectancy (ALE). To

conduct the ALE; we need to find some values that help us in that: 1) Finding Single Loss

Expectancy (SLE) which is the expected loss from a single incident, and it’s found by this

formula: SLE = Asset Value (AV) * Exposure Factor (EF) 1a) Exposure Factor (EF) is the

potential percentage of a specific asset loss by a specific threat. If not identified, it is considered

to be 1 or 100%, 1b) Asset Value (AV) is the value/cost of the asset. 2) Finding the Annual rate

of occurrence (ARO) the number of times the incident is expected to happen in a year. Annual

loss expectancy (ALE) = Single Loss Expectancy (SLE) * Annual rate of occurrence (ARO).

Then we can do the Cost/Benefit analysis using: ALE (before) – ALE (after) – ACS (Annual

Cost of Control) if the answer is Positive: the countermeasure should be implemented and if it’s

Negative: the countermeasure should not be implemented.

We assume that we will implement this system on a farm. Hence, we decided to provide a

scenario to explain the idea more and we defined some numbers regarding the needed

pieces/prices to conduct the calculations completely for this sample scenario.

3.4.2.1. Scenario

Samhan Farm is using the Smart Irrigation System to water the plants automatically and optimize

the process of watering plants along with the resources. They started by planting 500 soil

moisture sensors in different places on the farm. The value of each soil moisture sensor is

estimated to be 24 SAR and an exposure factor of 35%. The annual rate of occurrence of loss

because of sensor failure is quarterly and the farm could purchase new sensors for the value of 27

SAR for each to deploy them in the affected areas. Based on estimates, the acquisition of sensors

is anticipated to reduce the Annualized Rate of Occurrence (ARO) from 4 to 1.

3.4.2.2. Solution/Calculations

As shown in the results, to prevent such risk the farm might provide backup sensors as a

safeguard to be deployed in case of any failure and it will save 11250 SAR a year.

Another quantitative technique is to use the Expected monetary value (EMV) risk analysis [22];

all we need is the likelihood of risk and the expected cost of assets. After that, it multiplies the

cost with the likelihood and finally, it adds up all the results to find the overall projected risk, and

this value is called “contingency reserve” [22].

Expected Monetary Value (EMV) = Probability/likelihood * Cost. (9)

Likelihood Scale: Very High (81-100%), High (61-80%), Moderate (41-60%), Low (21-40%),

Very Low (0-20%).

Table 6. EMV Table

This simulation is only for illustrative purposes, and in real-life scenarios, there would be

variations in the types of sensors used, their values, and the companies involved. The asset value

could change, and a more comprehensive study would be conducted considering specific factors

and requirements of the Smart Irrigation System. Furthermore, this approach can be extended to

other Cyber-Physical Systems by adapting the calculations and considering relevant variables

specific to each system.

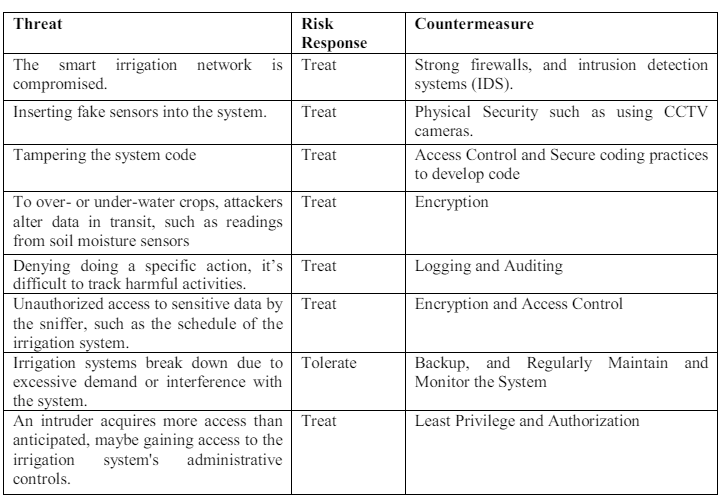

3.5. Risk Management

Based on the overall risks that we have assessed; the smart irrigation system must consider an

End-to-End security approach to maintain the security of the data from sensing to processing and

analysis. However, in the case of smart irrigation, countermeasures that help in managing risks

include encryption, access control, Logging, applying best practices, etc. So, the risk response

will show how we will handle the risks as follows:

Treat → Mitigating actions should be implemented to address threats that pose risks, with

the aim of reducing both their impact and probability.

Transfer → Share risk with 3rd parties such as insurers.

Tolerate → Accept risk and its consequences. Take no action to reduce the risk.

Terminate → Eliminate the risk by removing the risk source.

Table 7. Risk Treatment Response and Countermeasures

4.PROPOSED SECURE SYSTEM DESIGN FOR SMART IRRIGATION SYSTEM

The development of a secure Cyber-Physical System (CPS) model is focused on optimizing water

usage in agriculture through the integration of physical components such as sensors and pumps

with computational and communication technologies. This system design encompasses a

combination of hardware and software components working in harmony to accomplish effective

irrigation management. In addition, it’s crucial to address security considerations in the smart

irrigation system to protect against potential vulnerabilities and unauthorized access. These

components include:

Soil Moisture Sensor: Measures the moisture of the soil (dry or wet). It is usually inserted

into the plant roots to monitor the soil’s moisture level.

9V Battery: The power source utilized for powering the Arduino UNO board and other

electronic components in the system serves as their energy supply.

Relay: The electromagnetic switch functions as a control mechanism for operating the DC

motor, specifically the water pump, based on the moisture level detected by the soil

moisture sensor.

Arduino UNO: A microcontroller board that receives input from the soil moisture sensor,

processes the data, and controls the relay and water pump accordingly. Moreover, it’s

programmed using the Arduino programming language (Arduino IDE).

DC Motor (Water Pump): The DC motor is used as a water pump to deliver water to

plants. The motor is connected to the relay, and its operation is controlled by Arduino.

When the soil moisture level falls below a specific threshold, the Arduino board initiates

the activation of the relay, which in turn triggers the water pump to supply water to the

plants.

Tube: The water pump is connected to the irrigation system, establishing a link that

enables the water pump to deliver water to the plants as part of the irrigation process.

Female-to-Female Jumper Wires: Connect the soil moisture sensor.

Male-to-Female Jumper Wires: The soil moisture sensor is connected to both the

Arduino board and the relay, establishing a connection that enables the Arduino to receive

moisture level readings from the sensor and trigger the relay based on those readings.

4.1. Architecture Overview

The smart irrigation system comprises six interconnected subsystems that work in tandem to

manage and automate the irrigation process. Among these subsystems, certain components are

specifically designed to incorporate security features such as encryption and authentication.

These security subsystems play a vital role in protecting the system from unauthorized access,

data breaches, and ensuring the integrity and confidentiality of shared information within the

system. So, here are all the subsystems in our model:

Sensing Subsystem: Soil Moisture Sensors are part of this subsystem where they assess

soil moisture levels. The sensing subsystem plays a crucial role in the smart irrigation

system by collecting real-time data that is essential for making informed decisions

regarding the timing and quantity of water to be supplied to the plants.

Actuating Subsystem: Actuators, such as DC Water Pumps, are included in the actuating

subsystem. The actuating subsystem activates the relevant operations to manage the flow

of water to the plants based on the instructions received from the control subsystem. When

the control subsystem determines the need for irrigation, it triggers the activation of the DC

Water Pumps. This activation enables the pumping of water from the water supply to the

irrigation system.

Control Subsystem: Controllers and the Central Management System are part of the

control subsystem. Soil moisture sensors provide input to the controllers. It manages the

whole system by providing centralized control, monitoring, and data analysis.

Authentication Subsystem: The authentication subsystem is expressly built to provide

security and authenticate people, devices, or components seeking to access the smart

irrigation system. The username/password authentication technique is used to avoid

unauthorized access to the system. Access to the farming area is granted only if the

provided credentials are valid. If the credentials are verified successfully, the person is

granted access to the farming area. Conversely, if the credentials are invalid or not

authenticated, the person will be denied entry to the farming area.

Encryption Subsystem: The encryption subsystem is expressly built to provide security

and is responsible for safeguarding the data transported inside the smart irrigation system

by encoding it in a way that makes it unreadable to unauthorized parties.

Physical Subsystem: Where the smart irrigation system exists; it is the farming area that

consists of the plants.

In order to allow smooth data exchange and communication among system components, the

system can make use of a variety of connection and communication technologies. One such

technology is Wi-Fi, which offers wireless connectivity over short to medium distances. Wi-Fi is

commonly used within a local area network (LAN) environment to facilitate high-speed

communication between sensors, controllers, and the central management system. In a smart

irrigation system, certain subsystems may have a higher susceptibility to vulnerabilities due to

various factors such as power and resource limitations, lack of security measures, etc. A system

might have defects in either its digital (computing and networking) or physical (hardware and

environment) components. Here are a few subsystems that could potentially be more vulnerable

than other subsystems. The Sensing Subsystem: The system’s availability can be impacted by

frequent failures attributed to its limited power and computing capabilities. Also, the Physical

Subsystem: Farming areas are vulnerable to a wide variety of environmental hazards, including

wildlife, human interference, and extreme weather [27]. Lastly, the Authentication Subsystem:

Errors within the authentication subsystem can result in unauthorized access to the system.

Security must be built into both cyber and physical systems from the bottom up to ensure the

complete safety of Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS). To ensure security measures are incorporated

from the architectural level, it is important to follow best practices and principles. Here are some

steps to consider:

Secure by Design: Cybersecurity measures should be included early in the design process

rather than retroactively. It includes using secure coding practices [26].

Network Security: Firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and intrusion prevention

systems (IPS) are used to monitor and prevent illegal network access.

Secure Communication: To guarantee the confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of

data transmitted between system components, secure communication protocols are

employed. These protocols are designed to safeguard sensitive information from

unauthorized access, prevent data tampering, and verify the identity of communicating

parties. By implementing secure communication protocols, the smart irrigation system can

ensure the secure and reliable exchange of data between its components. Encryption

techniques and secure data exchange protocols (such as SSL/TLS) are employed to protect

against eavesdropping, tampering, or unauthorized access during data transmission.

Access Control: Limit access to the farming areas holding CPS components using access

control mechanisms. This ensures that only authorized individuals can interact with the

system.

Authentication: CPS architecture includes the authenticating technique for authenticating

users, devices, and components within the system. This verifies the identity of entities

before granting access.

Compromising one subsystem in a CPS can impact the security, integrity, reliability, and

functionality of other subsystems and the entire system. Implementing robust security measures is

crucial to mitigate risks and ensure system resilience. The security, reliability, and accessibility of

the CPS might be compromised in several ways such as:

Integrity: Data collected by a susceptible component (such as a sensor) may be

compromised. Control systems might make incorrect decisions if an attacker inserts false

data.

Reliability: Incorrect command execution due to a hacked actuator, for instance, might

lead to system failure or unexpected behavior.

Availability: If one part of the system is compromised, it might block access to the whole

of it. For instance, the availability of the system may be affected if a cyberattack such as a

distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) is conducted against the communication network

[13].

Confidentiality: If a compromised subsystem has access to sensitive data or can

communicate with other CPS components, that data may be compromised in the case of a

breach. Such as gaining access to the sensed data by the soil moisture sensor.

When communicating with systems outside of the system’s own network, the smart irrigation

system is vulnerable to attacks. The attack surface grows when more network connections,

interfaces, and protocols are implemented, accordingly, providing more entry points for

malicious actors. When a smart irrigation system, for example, links up with an online weather

forecasting service, it establishes a communication path that, if not properly safeguarded, may be

intercepted or otherwise disrupted. Having this data compromised might have devastating

impacts on agricultural productivity because it is used to make educated irrigation decisions.

Moreover, data communication is very susceptible. Encrypting information in transit between the

CPS and other systems protects it against eavesdropping and tampering. If an attacker obtains this

data, they may be able to hinder the CPS’s routine operations or even use it to their advantage in

well-organized attacks. Ex: a smart irrigation system that relies on a gateway for data analysis

and control. The system collects sensor data to determine optimal watering schedules for

different zones within a farm. If the communication between the smart irrigation system and the

gateway is not properly encrypted, an attacker could intercept the data and gain access to

sensitive information. By analyzing the data, the attacker could learn about the watering patterns

and crop types.

The architecture of CPS will evolve as new technologies become available. While future

technological developments hold the promise of more complex features, greater efficiency, and

heightened security, they will also provide new requirements for the design. Such as the

Adoption of Edge Computing, Advanced Machine Learning and AI Integration, Increased Use of

IoT Devices, and Enhanced Security Measures.

4.2. Implementation of Smart Irrigation CPS Security Model

The Smart Irrigation CPS security model is designed using a Data Flow Diagram (DFD) Figure 3

and simulated using the Tinkercad tool. This approach ensures thorough testing and validation

before implementing the system with Arduino UNO and other required equipment, enhancing

overall security. The model encompasses a system that can effectively sense the environment,

capture relevant data, and generate convenient output based on the sensed data. Lightweight

security mechanisms are implemented to ensure the integrity and security of the sensed data in

the Smart Irrigation CPS.

4.2.1. Circuit Design

The circuit in Figure 1 is created using one Soil moisture Sensor, one 9V Battery, one Relay, one

Arduino UNO, one DC Motor (water pump), one Tube, five female-to-female jumper wires, and

three male-to-female jumper wires.

4.2.2. Data Flow Diagram (using Microsoft Threat Modelling Tool)

4.2.3. Simulation results using Arduino UNO serial interface

4.2.4. Proposed Security Mechanisms

Smart irrigation systems, classified as Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) and Internet of Things

(IoT) devices, require robust security measures due to their developing nature and vulnerability to

potential threats. To ensure the secure functioning of the smart irrigation system, we can apply

some security mechanisms such as physical security, which is essential to protect the components

of the system. For example, the soil moisture sensor, Arduino UNO, and water pump, from

unauthorized access and tampering. Enclosing these components in secure enclosures can help

prevent physical damage and disruption caused by malicious individuals or environmental

factors. Another mechanism is redundancy which enhances availability and prevents violations.

By incorporating redundant sensors or backup systems, we ensure that the system continues

functioning even if one component fails or is compromised. To enhance security, it is crucial to

implement data encryption to safeguard transmitted data, employ authentication mechanisms, and

utilize secure communication protocols such as SSL/TLS. These measures contribute to

protecting sensitive information and ensuring secure communication within the smart irrigation

system. Encryption algorithms such as XOR can be employed to encrypt the data before

transmission, ensuring that even if intercepted, the data remains unreadable without the

decryption key. Authentication mechanisms, such as the requirement of valid credentials like a

username and password, are crucial for ensuring that only authorized users can access the system.

By implementing such mechanisms, the smart irrigation system maintains control over access and

enhances overall security. Lastly, the sensor fusion technique helps maintain data integrity by

filtering out false or erroneous sensor readings. By combining data from multiple sensors and

employing validation and anomaly detection algorithms, the smart irrigation system ensures

accurate and reliable data collection.

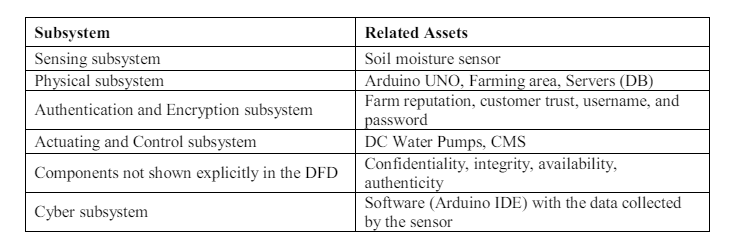

4.3. Assets to Security Model Tracing

By mapping and tracing the assets to the security model in Table 8, we found that all assets are

included in the model. Found assets in detail are a soil moisture sensor, controller, actuator, DC

water pump, and central management system (CMS).

Table 8. Assets to Subsystem Mapping Table

The location of an asset within the architecture directly impacts its vulnerability to exploitation.

There are several reasons for that including the different protection mechanisms for each layer.

For example, the cyber layer usually includes software that has different kinds of vulnerabilities

such as software bugs, unauthorized access, and data manipulation. Access controls and

encryption can be employed to safeguard the asset and enhance its protection. While the physical

layer protection mechanisms can include using environmental controls to protect from disasters,

and CCTV cameras to ensure security and detect tampering attempts. Physical assets can include

physical components such as sensors, actuators, and databases. If an attack occurs, the overall

authenticity, confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the system will be compromised.

By examining the security model, we concluded that assets are all over the model. This means

that assets are in every location in the model. In certain parts of the architecture, there are

currently no assets present because we have not yet implemented the mentioned assets such as the

mobile application for remote access and CMS discussed in previous sections. However, these

assets are considered as part of future work. Moreover, regarding the number of assets in every

location we believe that we do not have too many assets in a single location.

5.SECURITY ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED SMART IRRIGATION SYSTEMS

Among the defined subdomains in the previous section, the sensing, actuating, and cyber

subdomains are critical areas to address in the security analysis of a smart irrigation system.

Analyzing the sensing subdomain’s security is critical since hacked or manipulated sensors might

result in erroneous data readings, which can have serious ramifications for irrigation decisions.

Examining and securing the actuating subdomain is vital to prevent unauthorized or malicious

manipulation of the irrigation system. Potential vulnerabilities and dangers can be found and

addressed by conducting a security analysis of the sensing /actuating subdomains. This improves

the quality and reliability of sensor data while also preventing illegal control or manipulation of

the irrigation system, resulting in more efficient and secure functioning of the smart irrigation

system. Furthermore, the Cyber subdomain also is an important factor to consider while

analyzing the security of a smart irrigation system. It detects the vulnerabilities in the network

infrastructure and communication protocols, and it entails evaluating data transmission security.

Examining the cyber subdomain is critical for discovering vulnerabilities, guarding against cyberattacks, maintaining data privacy, providing secure access, improving system stability, and

meeting regulatory requirements. Securing the system against cyber threats, including malware

attacks and data breaches, is imperative.

The subdomains chosen for the security analysis include a variety of system features that are

crucial for guaranteeing the system’s security and integrity. By doing security analysis across the

system’s subdomains, you may completely examine and resolve any vulnerabilities and threats

across the various components of the smart irrigation system, therefore improving its overall

security posture. Doing the security analysis will give us an overview of the system security,

potential risks and vulnerabilities will be discovered and eliminated as a result of the security

analysis, assuring the overall security and dependability of the smart irrigation system. It aids in

the protection of data, the prevention of unauthorized access, the mitigation of physical and cyber

threats, the maintenance of system availability, and compliance with relevant requirements.

6.RESULTS & DISCUSSIONS

Each subdomain within the smart irrigation system has its own specific responsibility that

collectively enhances the overall operation of the entire system. The Sensing Subsystem is used

to gather moisture level data in real-time. It is crucial for monitoring the environment and

providing information for the system’s decision-making processes. The Actuating and Control

Subsystem manages actuators and other tangible components while processing data and directing

the overall operation of the system [1]. In this case, the pump will turn on if the soil is dry and

will turn off if the soil is wet, respectively. Also, the Cyber Subsystem, which includes software,

algorithms, and the ability to process data all make up this subsystem. Data analysis educated

decision making, and the ability for monitoring and control all rely on the cyber subsystem.

The following table 9 provides a cybersecurity checklist for smart irrigation systems to check the

security posture of the proposed system.

Table 9. Cybersecurity Checklist for Proposed Smart Irrigation System

7.CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the implementation of a smart irrigation system offers numerous benefits,

including improved water efficiency, reduced costs, and enhanced plant health. The integration of

advanced technologies, including sensors and actuators, enables the optimization of water usage

based on real-time environmental conditions. However, it is crucial to address vulnerabilities

such as limited power and computational capabilities within subsystems, as well as potential

security risks related to software and data management. Potential vulnerabilities in the Sensing

Subsystem include temporal delays that can disrupt the synchronization between the water pump

and soil sensors, physical manipulation, or malfunctioning of sensors, and interception of sensor

data. Additionally, there are software faults and defects in the Actuating and Control Subsystem

that can be exploited to control system behavior. Inaccurate reactions to sensor data due to poorly

constructed control logic could cause system breakdowns. Furthermore, cyberattacks, including

phishing, ransomware, and malware, target the Cyber Subsystem. Inadequate security measures

can lead to data breaches, resulting in the exposure of sensitive information. Viruses and worms

can infect the software used for code analysis and decision-making, especially if it is not

regularly updated. The system’s vulnerability is further increased by inadequate encryption

techniques. To mitigate these threats, comprehensive security measures should be incorporated

into the smart irrigation system’s operation and design. Enhancing the system’s resilience against

different threats involves implementing measures such as encryption techniques, secure data

transmission, authentication procedures, and frequent software updates. Additionally, physical

protection must be put in place to prevent manipulation or damage to the sensors and actuators. In

general, the analysis highlights the significance of addressing security issues in every subdomain

of the smart irrigation system to ensure data availability, confidentiality, integrity, and correct

system operation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to Prince Sultan University for their support.

REFERENCES

[1] S. Darshna, T. Sangavi, S. Mohan, A. Soundharya, and S. Desikan, “Smart Irrigation System,”

IOSR Journal of Electronics and Communication Engineering (IOSR-JECE), vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 32-

36, May-Jun. 2015.

[2] “Average Weather in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Year-Round,” Weather Spark, n.d.

https://weatherspark.com/y/104018/Average-Weather-in-Riyadh-Saudi-Arabia-Year-Round.

[3] “Saudi Vision 2030 Overview,” Saudi Vision 2030, [Online]. Available:

https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/en/vision2030/overview/#:~:text=Vision%202030%20creates%20a%20thriving,and%20prosperous%20futur

e%20for%20all

[4] Obaideen, K., Yousef, B. A., AlMallahi, M. N., Tan, Y. C., Mahmoud, M., Jaber, H., & Ramadan,

M. (2022). An overview of smart irrigation systems using IoT. Energy Nexus, 7, 100124.

[5] Rad, C. R., Hancu, O., Takacs, I. A., & Olteanu, G. (2015). Smart monitoring of potato crop: a

cyber-physical system architecture model in the field of precision agriculture. Agriculture and

Agricultural Science Procedia, 6, 73-79.

[6] Alexandra, C., Daniell, K. A., Guillaume, J., Saraswat, C., & Feldman, H. R. (2023). Cyberphysical systems in water management and governance. Current Opinion in Environmental

Sustainability, 62, 101290.

[7] Basheer, A. K., Ali, A. B., Elshaikh, N. A., Alhadi, M., & Altayeb, O. A. (2015). Performance’s

Comparison Study between Center Pivot Sprinkler and Surface Irrigation System. t J. Eng. Works,

2, 6-10.

[8] Adeyemi, O., Grove, I., Peets, S., & Norton, T. (2017). Advanced monitoring and management

systems for improving sustainability in precision irrigation. Sustainability, 9(3), 353.

[9] Sontowski, S., Gupta, M., Chukkapalli, S. S. L., Abdelsalam, M., Mittal, S., Joshi, A., & Sandhu, R.

(2020, December). Cyber attacks on smart farming infrastructure. In 2020 IEEE 6th International

Conference on Collaboration and Internet Computing (CIC) (pp. 135-143). IEEE.

[10] Bwambale, E., Abagale, F. K., & Anornu, G. K. (2022). Smart irrigation monitoring and control

strategies for improving water use efficiency in precision agriculture: A review. Agricultural Water

Management, 260, 107324.

[11] de Araujo Zanella, A. R., da Silva, E., & Albini, L. C. P. (2020). Security challenges to smart

agriculture: Current state, key issues, and future directions. Array, 8, 100048.

[12] Akter, S., Mahanta, P., Mim, M. H., Hasan, M. R., Ahmed, R. U., & Billah, M. M. (2018).

Developing a smart irrigation system using arduino. International Journal of Research Studies in

Science, Engineering and Technology, 6(1), 31-39.

[13] Operations Manager, “What are confidentiality, integrity and availability in information security?,”

DeltaNet, 31-Mar-2022. [Online].https://www.delta-net.com/knowledge

base/compliance/information-security/what-are-confidentiality-integrity-and-availability-ininformation-security/

[14] National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2012). NIST Special Publication 800-30, Risk

Management Guide for Information Technology Systems.

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/legacy/sp/nistspecialpublication800-30r1.pdf

[15] CIA triad. (n.d.). Fortinet. Retrieved October 10, 2023, from

https://www.fortinet.com/resources/cyberglossary/cia-triad

[16] Smart irrigation technology: Controllers and sensors – Oklahoma State University. (2017, February

1). Okstate.edu. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/smart-irrigation-technology-controllersand-sensors.html

[17] Threat modeling methodology: STRIDE. (n.d.). Iriusrisk.com. Retrieved October 10, 2023, from

https://www.iriusrisk.com/resources-blog/stride-threat-modeling-methodologies

[18] Types of attackers. (2013, August 8). FutureLearn. https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/cybersecurity-landscape/0/steps/60317

[19] Wheeler, E. (2011). Security risk management: Building an information security risk management

program from the Ground Up. Elsevier.

[20] Qualitative vs. quantitative risk assessment (2021) ISACA. Available at:

https://www.isaca.org/resources/news-and-trends/isaca-now-blog/2021/qualitative-vs-quantitativerisk-assessment

[21] Quantitative risk analysis (definition, benefits, and steps) – indeed (2022). Available at:

https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/quantitative-risk-analysis

[22] Usmani, F. et al. (2022) Expected monetary value (EMV): A guide with examples, Home Page.

Available at: https://pmstudycircle.com/expected-monetary-value-emv/

[23] Ham, J. V. D. (2021). Toward a better understanding of “cybersecurity”. Digital Threats: Research

and Practice, 2(3), 1-3.

[24] Song, H., Fink, G. A., & Jeschke, S. (Eds.). (2017). Security and privacy in cyber-physical systems:

foundations, principles, and applications. John Wiley & Sons.

[25] “2022-28214 : During an update of SAP BusinessObjects Enterprise, Central Management Server

(CMS) – versions 420, 430, Authentication.” n.d. [Online]. https://www.cvedetails.com/cve/CVE2022-28214/.

[26] “Smart irrigation technology: Controllers and sensors – Oklahoma state university,” Okstate.edu, 01-

Feb-2017. [Online]. https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/smart-irrigation-technologycontrollers-and-sensors.html.

[27] “What are irrigation sensors, and how do they work in smart irrigation systems?,” Smart Watering

an autonomous drip irrigation system, 20-Mar-2022. [Online]. https://smartwatering.com/2022/03/20/irrigation-sensors-in-irrigation-systems/