IJCNC 05

ADVANCED PRIVACY SCHEME TO IMPROVE ROAD

SAFETY IN SMART TRANSPORTATION SYSTEMS

Ali Muayed Fadhil1,4 , Norashidah Md Din2, Norazizah Binti Mohd Aripin3 And Ali Ahmed Abed4

1 College of Graduate Studies, University Tenaga Nasional, Jalan IKRAM- UNITEN, Kajang, Malaysia

2 Instituteof Energy Infrastructure, University Tenaga Nasional, Jalan IKRAM-UNITEN Kajang, Malaysia

3 Institute of Power Engineering, University Tenaga Nasional, Jalan IKRAM- UNITEN Kajang, Malaysia

4Department of Computer Engineering, University of Basrah, Iraq

ABSTRACT

In -Vehicle Ad-Hoc Network (VANET), vehicles continuously transmit and receive spatiotemporal data with neighboring vehicles, thereby establishing a comprehensive 360-degree traffic awareness system. Vehicular Network safety applications facilitate the transmission of messages between vehicles that are near each other, at regular intervals, enhancing drivers’ contextual understanding of the driving environment and significantly improving traffic safety. Privacy schemes in VANETs are vital to safeguard vehicles’ identities and their associated owners or drivers. Privacy schemes prevent unauthorized parties from linking the vehicle’s communications to a specific real-world identity by employing techniques such as pseudonyms, randomization, or cryptographic protocols. Nevertheless, these communications frequently contain important vehicle information that malevolent groups could use to Monitor the vehicle over a long period. The acquisition of this shared data has the potential to facilitate the reconstruction of vehicle trajectories, thereby posing a potential risk to the privacy of the driver. Addressing the critical challenge of developing effective and scalable privacy-preserving protocols for communication in vehicle networks is of the highest priority. These protocols aim to reduce the transmission of confidential data while ensuring the required level of communication. This paper aims to propose an Advanced Privacy Vehicle Scheme (APV) that periodically changes pseudonyms to protect vehicle identities and improve privacy. The APV scheme utilizes a concept called the silent period, which involves changing the pseudonym of a vehicle periodically based on the tracking of neighboring vehicles. The pseudonym is a temporary identifier that vehicles use to communicate with each other in a VANET. By changing the pseudonym regularly, the APV scheme makes it difficult for unauthorized entities to link a vehicle’s communications to its real-world identity. The proposed APV is compared to the SLOW, RSP, CAPS, and CPN techniques. The data indicates that the efficiency of APV is a better improvement in privacy metrics. It is evident that the AVP offers enhanced safety for vehicles during transportation in the smart city.

KEYWORDS

VANET, Privacy Protection, Smart Transportation System, Adversary, Pseudonym Change, Urban Area.

1. INTRODUCTION

Vehicle Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs) represent an evolving technological advancement that facilitates inter-vehicle and vehicle-infrastructure communication, thereby augmenting road safety, traffic efficacy, and driver support [1]. Vehicles must establish secure and confidential communication channels to deliver the intended services effectively. This ensures the integrity of the system and safeguards the privacy of the driver. Privacy schemes can provide anonymity to vehicles in a VANET, making it difficult for unauthorized entities to track individual vehicles’ movements and identify their owners or drivers. By concealing the identity of the cars, privacy schemes protect users’ privacy [2]. VANETs are designed to gather and exchange confidential data about their passengers, encompassing geographical coordinates, velocity, and driving patterns. Ensuring the protection of this information is paramount to protect the privacy of individuals and mitigate the risk of unauthorized tracking or profiling. Security breaches have the potential to result in the dissemination of fabricated information or the manipulation of communication channels between vehicles by malicious entities, thereby presenting a significant peril to the public’s safety [3].

In addition to protecting identity and location information, privacy schemes can ensure the confidentiality of the data transmitted over the VANET. Using encryption and secure communication protocols, sensitive information can be encrypted and decrypted only by authorized recipients, reducing the risk of unauthorized eavesdropping [4]. VANETs depend on wireless communication among vehicles, thereby establishing a dynamic and self-organizing network. Nevertheless, protecting privacy was established as a crucial concern considering the growing implementation of VANET. Different privacy schemes have different strengths and limitations, and their effectiveness can depend on factors such as the network architecture, threat model, and cryptographic mechanisms employed [5].

There are several potential privacy attacks in VANET, such as [6][7]:

(i) Eavesdropping: The process of gathering information from various sources to obtain valuable insights for analysis and subsequent utilization, potentially serving as a precursor to subsequent attacks.

(ii)Denial of Service (DoS): is widely recognized as a highly potent attack aiming to compromise the availability requirement. The execution of this attack can manifest in various forms, such as channel jamming and resource consumption attacks.

(iii) Virus or Malware Attack: is a type of cybersecurity threat that involves malicious software (malware) infecting a computer system, network, or device to cause harm, steal sensitive information, or disrupt normal operations.

(iv) Man in the Middle (MITM) Attack: in this method the interception of communication by an attacker results in unauthorized entry to the information sent between two parties. This can happen in unsecured public Wi-Fi networks or compromised network infrastructure.

Privacy schemes can protect against traffic analysis attacks, where an adversary attempts to infer sensitive information by analyzing traffic patterns. By employing techniques such as dummy traffic generation or mix-zone protocols, privacy schemes can obscure traffic patterns and make it difficult for attackers to extract meaningful information [8]. Scientists have put forward different strategies to enhance the level of confidentiality for drivers. The absence of message broadcasting for a particular duration heightens the probability of accidents [9].

It’s important to note that while privacy schemes bring significant improvements, they may also introduce some trade-offs. These include increased communication overhead, the potential impact on routing efficiency, and the need for key management and trust mechanisms [10]. However, carefully designing and implementing privacy schemes can minimize these drawbacks while reaping enhanced privacy benefits in VANETs [11]. One potential avenue for improving road safety is through direct communication capabilities within vehicles, which enables them to broadcast information to other entities known as Beacon Messages (BMs) by the vehicle, which can be received by any entity within its communication distance. To enhance awareness among vehicles, it is imperative to implement advanced safety features such as collaborative collision warnings and lane change alerts [12].

The efficacy of VANET safety implementations heavily relies on the continuous availability of location information. Therefore, the occurrence of silent periods can potentially harm their effectiveness, potentially leading to unavoidable accidents. Thus, a scientific difficulty arises regarding the delicate equilibrium between privacy and safety, as implementing a brief period of silence would augment safety measures while concurrently enhancing the level of privacy; conversely, arranging privacy would compromise safety [13]. Privacy schemes for VANETs are commonly assessed using various assumptions and mobility models concerning diverse privacy metrics. The vehicle interacts to track neighboring vehicles within a defined range in anticipation of an impending accident. Subsequently, it initiates a period of silence and modifies the pseudonym change by transmitting its location information to neighbouring vehicles [14].

The primary contributions of this article summarized as:

• Propose an Advanced Privacy Vehicle Scheme (APV) that improves the effectiveness of VANET safety applications in addition to maintaining privacy. We assess and contrast multiple privacy schemes by utilizing a standardized privacy metric.

• The implementation of the (APV) algorithms involves employing the principle of a silent time frame, wherein the pseudonym of a vehicle is changed periodically by the tracking of neighboring vehicles. To reduce sensitive data exchange while maintaining communication in the smart transportation systems.

• The objective of this study is to assess and contrast the degree of privacy and network efficiency of the APV with other privacy schemes, namely RSP, CPN, SLOW, and CAPS.

This paper is segmented into 5 sections. Section 2 presents related works to recent techniques on privacy and security in VANET. Section 3 is the system model, and section 4 the proposed scheme. Section 5 is the simulation performance, and Section 6 serves as the conclusion part and discusses potential future projects.

2. RELATED WORK FORMAT

Problems with location privacy are regarded as a critical factor in the successful implementation of a vehicle network. Several privacy structures have been proposed to optimize the driver’s privacy measures while minimizing the associated security costs. In [15], the periodical pseudonym change alters their pseudonyms at predetermined intervals or arbitrarily. This analysis aims to assess the impact of various parameters on the efficacy of (PPC) scheme, specifically by quantifying the magnitude of the anonymity set. This evaluation will be conducted under two distinct pseudonym lifetime distributions: uniform and reciprocal. In [16], the Random Silent Period (RSP) keeps quiet for a period that is consistently determined at random within a predetermined range and permits the temporary change of a vehicle’s pseudonym. It has been assessed that the quiet period should encompass both constant and variable periods. Considering the outcomes of the simulation, it appears that implementing the silent period proposal leads to a notable reduction in the duration of continuous tracking for a given node.

Andreas et al. [17] introduced a Coordinated Silent Period (CSP), which involves coordinating all vehicles within the network to maintain a state of silence and synchronously alter their pseudonyms. The CPS scheme offers the most optimal level of protection within the framework of these concepts. The work in [18] suggests the SLOW scheme, which considers safety protocol; in the SLOW scheme, vehicles should only operate silently when their velocity is below a specified threshold, thereby reducing the likelihood of accidents.

In[19], a collaborative pseudonym alteration strategy is predicated on the number of adjacent entities. The qualitative analysis of anonymity afforded by the CPN scheme is made between the scheme under consideration and its counterpart scheme lacking cooperation. The CPN counts neighbors using beacons and checks if they are inside the set area. Karim et al. [20] propose the Context-aware Privacy Scheme (CAPS). Initiating a period of silence and strategically ending it depending on contextual factors to make vehicles calculate the optimal timing for changing their pseudonyms. To assess the efficacy of a collision alert safety application to ascertain its suitability for implementation in safety applications.

The authors in [21] propose establishing mixed-use zones at strategically selected locations within VANET. An adversary cannot see vehicle communications in a mix-zone. To make vehicle movements unpredictable, it is usually installed at road crossings. [22] suggests a contextbased location privacy scheme (CLPS) to enable the vehicle to alter its aliases depending on the context and the potential for linking. that challenges the suggested method. A cheating detection technique detects misbehaving automobiles and evaluates the success of pseudonym changes.

Ferroudja et al. [23] propose building a location privacy solution that maintains road safety application quality of service. The proposed privacy mechanism is called the Estimation of Neighbours Position privacy technique (ENeP-AB), where pseudonym change depends on neighbors’ placements. In [24], the Cooperative Pseudonym Exchange scheme protects users’ anonymity on VANETs. Providing a means for vehicles to swap their identities collaboratively introduces a mechanism for vehicles to modify their pseudonym schemes, thereby introducing confusion for potential adversaries and enhancing privacy. Ikjot et al. [25] One way to overcome this challenge is to use pseudonyms instead of vehicle IDs. Numerous Pseudonym Management Techniques PMTs can help, focusing on the impact of strategic deployment of intelligent adversaries on the effectiveness of tracking operations. while employing various Pseudonym Administration Techniques.

Work in[26] introduced Concerted Silence-Based Location Privacy (CSLPPS) that guarantees message integrity and source location privacy while reducing communication overhead to meet the security demands of the beaconing mechanism in (IoV) services that utilize location and vehicle network safety applications. In [27] transmission Range Changes to introduce a Location Privacy-Preserving Scheme to guarantee anonymous and untraceable engagement in locationbased services within the (IoV) and enhance the safety applications of vehicular networks. In [28] offers an experimental location privacy-preserving approach that lets vehicles communicate accurate real-time location data to the location-based services server without being tracked by attackers.

In [29] The present study aims to propose a novel and comprehensive pseudonym-changing system (PCS) that uses vehicle context and real-time traffic patterns to improve pseudonymchanging efficiency. The simulation results show the suggested PCS exhibits superior performance compared to existing approaches. in [30] introduces an effective pseudonym consumption model that considers vehicles traveling similar estimated locations and directions. BSM is exclusively distributed to the vehicles that are pertinent to its application. The proposed scheme’s efficacy, compared to the base schemes, is substantiated through comprehensive simulations.

A significant challenge is the development of privacy-preserving protocols for communication invehicle networks that are both efficient and scalable. While ensuring an adequate level of communication, these protocols should restrict the transmission of sensitive information to a minimum. From the related work, there are research gaps in parameters for system improvement like pseudonym number when leading to high overhead in the network and the traceability must be decreased to prevent the system from eavesdropping attacks.

3. THE PROPOSED ADVANCE VEHICLE PRIVACY SCHEME

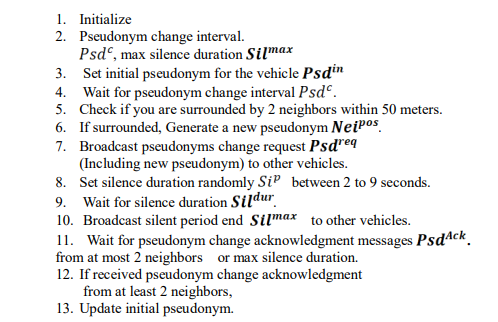

Propose an Advanced Privacy Vehicle Scheme (APV) that effectively enhances the privacy and safety aspects of Vehicle Ad-Hoc Networks safety applications. Using the silent period characteristic, it is controlled with Pseudonym changes and neighbor numbers in the specified area range with APV Scheme to enhance privacy and network connectivity. This method makes our system perform best when compared with another privacy scheme when maintaining the integrity of privacy protection metrics. The proposed algorithm and framework are described below.

3.1. Description of APV Pseudo-Algorithm

Each automobile is defined as, , effectively safeguarding the driver’s privacy during communications with a collection of authorized pseudonym, which must be obtained through an offline process in VANET. Every vehicle within the system is required to alter its pseudonym every 30 seconds after the silent period according to the number of the neighbor’srange.

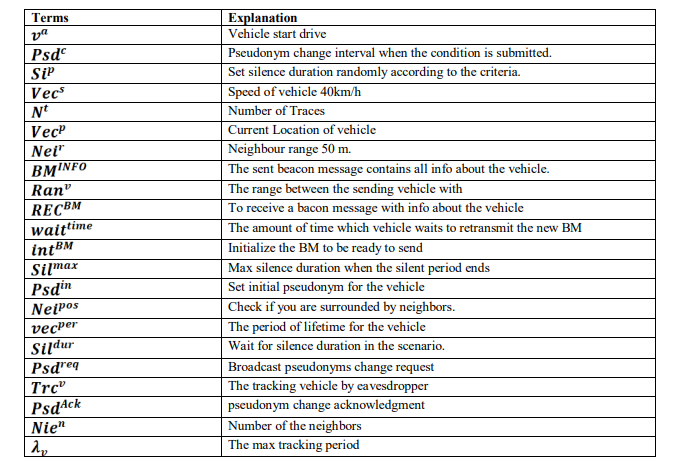

Table 1. APV Terms, and Explanations

3.2.. Algorithm Advanced Privacy Vehicle Scheme (APV)

During the advanced privacy vehicle scheme algorithm there different 7 instruction conditions during the process of the algorithm related to pseudonym range(30s,60s,90s,120s) and silent period, neighbor number, and beacon message generated so the complexity of the proposed protocol as described below: O (7 * n) = O(n).

4. SYSTEM FRAMEWORK

Based on the specified criteria and attributes of VANET safety applications, The System Model encompasses a network model and an attacker model, which collectively represent the essential aspects of employing certificates within the context of the VANET system [31]. The system includes adversary elements that intercept messages sent by vehicles and monitor their movements. The adversary is employed to quantify privacy achieved, as measured by various widely recognized metrics, including entropy, traceability, and statistics related to pseudonym usage. Hence, it is common practice to integrate a distinct vehicular traffic simulator with a network simulator to simulate vehicular traffic [32].

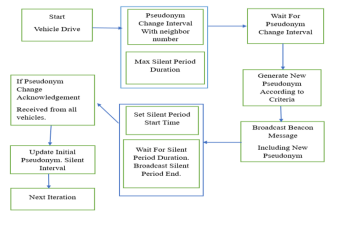

4.1. -Network Model

Vehicles: is supplied by an on-board unit capable of receiving and transmitting in the vehicular networks. According to the safety application specifications, the onboard unit (OBU) is responsible for transmitting Basic Safety Messages (BMs) that include the position, speed, and direction of the vehicle at the present moment. These transmissions occur within a communication radius of 300 meters, utilizing the Dedicated Short-Range Communications (DSRC) technology. Car communication uses Public Key Infrastructure proofs for secure transmission. Consequently, the act of altering the pseudonym employed necessitates the acquisition and implementation of a fresh certificate [33].

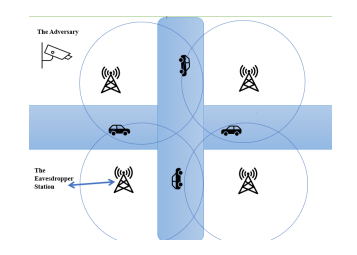

Figure 1. The Farmwork Diagram of APV

Roadside Unit: The traffic signs are at designated locations across a road or highway. A Roadside Unit (RSU) assumes the responsibility of message routing, expanding the scope of communication, providing vehicle internet access on roadways, and acting as an intermediary between automobiles and reliable entities. One of the most intriguing aspects pertains to the communications between vehicles and infrastructure[34], referred to as vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communications, as described in the figure below.

System Authorities: The role of each authority varies depending on its type, encompassing tasks such as pseudonym distribution, issuance, resolution, and revocation processes. The fulfillment of the accountability requirement by system authorities is of utmost importance as it enables the tracking and identification of users who engage in inappropriate behavior.

Figure 2. The Network Model.

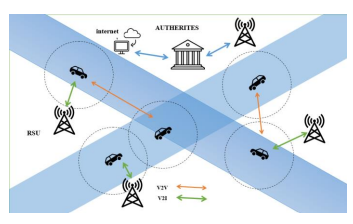

4.2. Adversary Attack Model

The Eavesdropper: The primary purpose of the eavesdropper’s effectiveness is passively monitoring the wireless medium and subsequently relaying the received beacon signals to the vehicle tracker system. In this scenario, the adversary employs distributed eavesdropping stations, strategically determining their required quantity based on an examination of the applicable vehicles’ typical transmission range. The Global Passive Adversary is commonly used in order to determine the effectiveness, of the type of

adversary of their schemes[35].

Figure 3. The Adversary Model.

Vehicle Tracker: This module serves as the primary component responsible for gathering beacons from various eavesdroppers and exporting their information while ensuring the elimination of duplicate entries. Additionally, the system can execute the NNPDA tracking algorithm, which enables the reconstruction of vehicle trajectories based on intercepted beacons[36]. This functionality also facilitates the computation of diverse privacy metrics. The adversary is strategically deploying eavesdropping stations in adherence to a standardized protocol, with each station having a transmission range of 300 meters for vehicles [37]. as

described in figure 3.

5. SIMULATION PARAMETER & PERFORMANCE MATRICES

5.1. Performance Metrics

The initial classification of metrics is predicated upon the fundamental notion of privacy, which shall be delineated as follows:

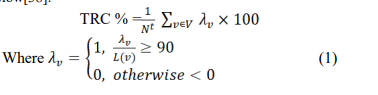

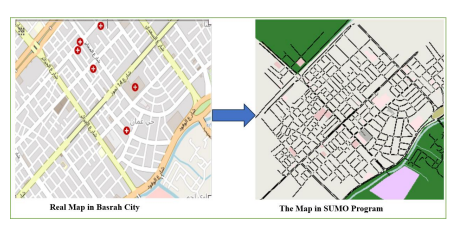

Traceability: The location privacy parameter measures vehicle trace reconstruction accuracy for a duration exceeding 90% of the original atoms using the beacons generated and obtained by an adversary. This metric falls under the category of location privacy metrics. The traceability metric TRC is explained below[38].

Maximum Anonymity Per Trace: is influenced by an ambiguity between a vehicle and others present in its surrounding area. The target vehicle’s location cannot be identified among the other vehicles[38].

Maximum Entropy Per Trace: The assumption that all vehicles are equally like the tracked vehicle is incorrect, as certain vehicles are far more likely to exhibit similarities. Entropy can be characterized by random variable uncertainty. The calculation of entropy is dependent on the adversary-assigned probability distribution when a pseudonym change occurs [38]

Total Pseudonym Changes: It denotes the cumulative number of pseudonym alterations carried out by all accessible vehicles throughout the simulation. The degree of elevation positively correlates considering the degree of regional secrecy. When this is high, it will be best for the privacy scheme but may increase overhead for the system.

Total Sent Beacon Number: The metric denotes an overall count of a series of accessible vehicles’ beacon messages sent out during the simulation. As the elevation increases, there is an improvement in safety measures; however, this is accompanied by a decline in network communications, increased overhead, and heightened packet congestion.

Confusions Per Pseudonym Change: Frequent alteration of pseudonyms will escalate security costs to heighten the level of confusion experienced while altering pseudonyms; it is imperative to implement specific strategies

5.2. Simulation Setup

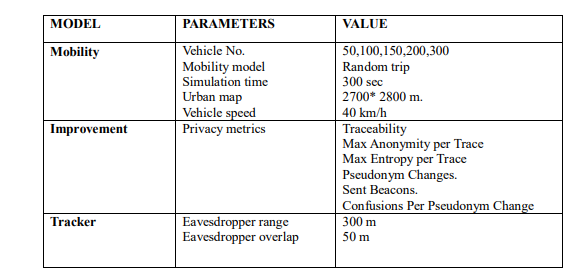

The number of simulation iterations was carried out for two distinct case studies: a Basrah scenario. It is necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation to assess the APV aspect and examine how it affects privacy in location and the efficiency of the network. The Open Street Map (OSM) contributors’ database was utilized to extract a specific section of the map of Basra, Iraq, with dimension (2.8km * 2.7km) as shown in the figure below and establishing the simulation parameters, an examination of the behavior exhibited by each scheme can be conducted, facilitating a comparative analysis between them. The map obtained from (OSM) was converted into a network of roads. compatible with the SUMO mobility simulator[39]. This file was then utilized in the OMNET++ network [40] environment to facilitate simulation. employed an additional extension known as PREXT[41], a privacy extension developed using the Veins framework[42]. The PREXT system incorporates a collection of techniques aimed at preserving privacy. We conduct a comparative analysis of the APV scheme about several other schemes that employ distinct techniques.

To evaluate the degree of privacy achieved it is essential to establish a comprehensive framework comprising a range of metrics that can evaluate privacy. These metrics include the Anonymity Set Size and Entropy, Traceability, and confusion per pseudonym change. Demonstrate the attained level of location privacy metrics of the APV with related Privacy schemes.

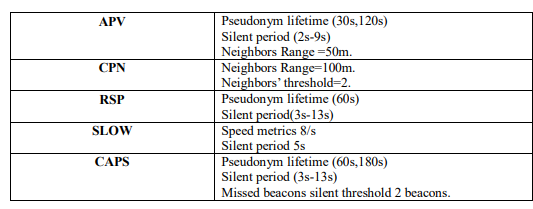

Table 2. Simulation Parameters and Values.

Figure 5. The Map Area Used in The Simulation.

Table 3. Privacy Scheme Metrics.

5.3. Results & Discussion

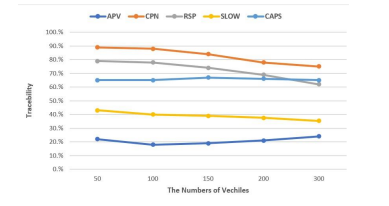

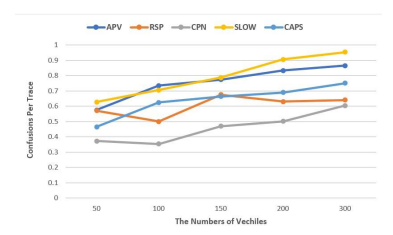

The APV scheme’s performance in traceability in the Figure (6) metric exhibited a significant advantage over SLOW, RSP, CAPS, and CPN, with a notable margin of approximately 12% to 25%. As the traceability is low, it is improving the system’s privacy performance. The level of traceability is slightly increased as the vehicle count rises. The decline in privacy levels can be attributed to the increased vehicular density, which facilitates the attacker’s ability to intercept messages from legitimate vehicles.

Figure 6. The Resulting Traceability Between My Scheme APV with SLOW, RSP, CPN, CAPS.

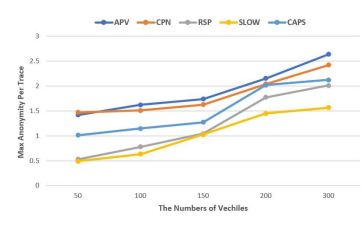

Figure 7 shows that our scheme gets the best result compared to other scenarios in different vehicle densities. As the vehicle density increases, there is an observed enhancement in the level of privacy achieved. A higher vehicle density corresponds to a better privacy level. The APV scheme gets the same result in the small destined, about 50 and 100 vehicles. After that, it gets the best result when increasing the vehicle densities according to the criteria of our scheme Based on the rate of pseudonym alterations and the range of the vehicle during the silent period.

Figure 7. Maximum Anonymity Per Trace Between All Schemes.

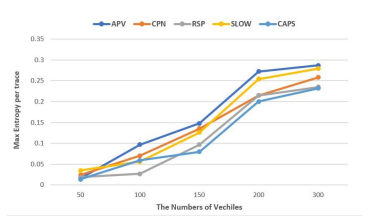

Figure 8.Maximum Entropy Per Trace Between All Schemes.

In Figure 8, the APV scheme in the Maximum entropy per trace gets enhancing results when compared with other privacy schemes in all scenarios except the small scenario according to a limited number of vehicles made in a small urban city. The APV scheme demonstrated a more pronounced level of superior performance of about 0.3 at 300 vehicles.

Figure 9.Confusions Per Trace Between All Schemes.

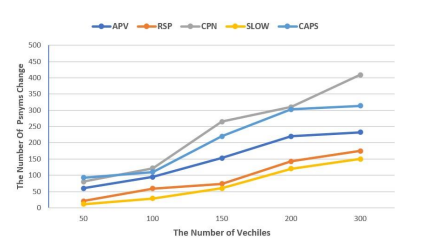

Every scheme has its unique approach to managing pseudonym changes and expiration policies. As in Figure 9, APV is positioned at the forefront of pseudonym consumption for increased usage. In the remainder of this scheme, which utilized a significant quantity of pseudonyms, when the number of confusions increased, increasing overhead in the system will decrease the attacker for the system.

Figure 10.The total of pseudonyms changes according to vehicles levels.

In Figure 10, The frequency of pseudonym changes in schemes, wherein a vehicle could autonomously determine, based on its state or the states of neighboring vehicles, whether it can go silent and change pseudonyms, Increases the total number of vehicles in the network Pseudonym changes hurt network efficiency and lead to an increase in packet loss. Systems should strive for a harmonious equilibrium between safeguarding privacy and network performance. The AVP has good Network performance compared to other projects.

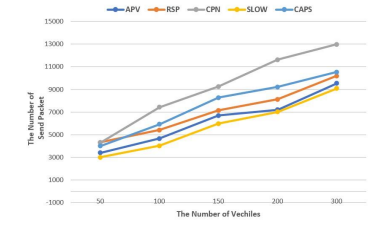

Figure 11.The number of sent packets according to different numbers of vehicles between all schemes

The data presented in Figure 11 illustrates the quantity of transmitted packets about the fluctuation of vehicle densities. The Number of Sent Packets With the rise in vehicular densities across all schemes, The APV scheme takes the diminished number of sent packets. In contrast, the CPN scheme exhibits the highest number of transmitted beacons, primarily attributed to its non-utilization of silent periods. For safety operations, the number of produced beacons is critical. and is affected by the privacy scheme.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Implementing safety applications in VANETs facilitates the exchange of messages between vehicles in proximity at regular intervals. This information exchange enhances drivers’ contextual comprehension of the driving environment, thereby significantly enhancing overall traffic safety. Privacy mechanisms in VANETs serve the purpose of protecting the identities of vehicles as well as their respective owners or drivers. This study aims to present an Advanced Privacy Vehicle Scheme (APV) that effectively improves the privacy and safety features of Vehicle Networks safety applications. When the APV scheme undergoes comparison to other projects in the urban scheme. Our scheme provides the best performance privacy metrics against the scheme in a simulation program with different numbers of vehicles according to varying factors in the framework the range of silent period and pseudonym change and several neighbors. The comprehensive findings suggest that the mentioned approach can be beneficially employed. It is evident that the AVP offers enhanced safety for vehicles during transportation in the smart city because decreases traceability for the vehicle from eavesdropping attacks and improves all the related parameters that improve the privacy of vehicles on the road.

FUTURE SCOPE & LIMITATIONS

The future scope may be using authentication in privacy scheme scenarios with different criteria and integration of privacy schemes with Modern technologies including artificial intelligence, fog computing, and data dissemination systems. The limitation of the privacy scheme is used in urban areas not in highway scenarios.

REFERENCES

[1] W. Afifi, H. A. Hefny, and N. R. Darwish, “A Cooperative Localization Method based on V2I Communication and Distance Information in Vehicular Networks,” International Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 53–70, 2021, doi: 10.5121/ijcnc.2021.13604.

[2] A. Waheed et al., “A Comprehensive Review of Computing Paradigms, Enabling Computation Offloading and Task Execution in Vehicular Networks,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 3580–3600, 2022, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3138219.

[3] M. J. N. Mahi et al., “A Review on VANET Research: Perspective of Recent Emerging Technologies,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 65760–65783, 2022, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3183605.

[4] M. Kabbur, R. Anand, and V. Arul Kumar, “Mar security: Improved security mechanism for emergency messages of vanet using group key management &cryptography schemes (GKMC),” International Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 101–121, 2021, doi: 10.5121/ijcnc.2021.13407.

[5] A. K. Malhi, S. Batra, and H. S. Pannu, “Security of vehicular ad-hoc networks: A comprehensive survey,” Computers and Security, vol. 89, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2019.101664.

[6] M. L. Bouchouia et al., “A survey on misbehavior detection for connected and autonomous vehicles,” Vehicular Communications, vol. 41, p. 100586, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.vehcom.2023.100586.

[7] R. Abassi, “VANET security and forensics: Challenges and opportunities,” WIREs Forensic Science, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 1–13, 2019, doi: 10.1002/wfs2.1324.

[8] N. Tabassum and C. R. K. Reddyy, “Review on QoS and security challenges associated with the internet of vehicles in cloud computing,” Measurement: Sensors, vol. 27, no. August 2022, p. 100562, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.measen.2022.100562.

[9] H. J. Nath and H. Choudhury, “A privacy-preserving mutual authentication scheme for group communication in VANET,” Computer Communications, vol. 192, no. February, pp. 357–372, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.comcom.2022.06.024.

[10] S. A. Jan, N. U. Amin, M. Othman, M. Ali, A. I. Umar, and A. Basir, “A Survey on PrivacyPreserving Authentication Schemes in VANETs: Attacks, Challenges and Open Issues,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 153701–153726, 2021, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3125521.

[11] I. Ali and F. Li, “An efficient conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme for Vehicle ToInfrastructure communication in VANETs,” Vehicular Communications, vol. 22, p. 100228, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.vehcom.2019.100228.

[12] H. Tan, W. Zheng, Y. Guan, and R. Lu, “A Privacy-Preserving Attribute-Based Authenticated Key Management Scheme for Accountable Vehicular Communications,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 3622–3635, 2023, doi: 10.1109/TVT.2022.3220410.

[13] M. Safkhani, S. Kumari, M. Shojafar, and S. Kumar, “An authentication and key agreement scheme for smart grid,” Peer-to-Peer Networking and Applications, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1595–1616, 2022, doi: 10.1007/s12083-022-01305-8.

[14] M. Babaghayou, N. Labraoui, A. A. Abba Ari, N. Lagraa, and M. A. Ferrag, “Pseudonym changebased privacy-preserving schemes in vehicular ad-hoc networks: A survey,” Journal of Information Security and Applications, vol. 55, no. October, p. 102618, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.jisa.2020.102618.

[15] Y. Pan, J. Li, L. Feng, and B. Xu, “An analytical model for random pseudonym change scheme in VANETs,” Cluster Computing, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 413–421, 2014, doi: 10.1007/s10586-012-0242-7.

[16] L. Huang, K. Matsuura, H. Yamanet, and K. Sezaki, “Enhancing wireless location privacy using silent period,” IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, WCNC, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1187–1192, 2005, doi: 10.1109/WCNC.2005.1424677.

[17] A. Tomandl, F. Scheuer, and H. Federrath, “Simulation-based evaluation of techniques for privacy protection in VANETs,” International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications, pp. 165–172, 2012, doi: 10.1109/WiMOB.2012.6379070.

[18] L. Buttyán, T. Holczer, A. Weimerskirch, and W. Whyte, “SLOW: A practical pseudonym changing scheme for location privacy in VANETs,” 2009 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference, VNC 2009, pp. 1–8, 2009, doi: 10.1109/VNC.2009.5416380.

[19] Y. Pan and J. Li, “Cooperative pseudonym change scheme based on the number of neighbors in VANETs,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 1599–1609, 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jnca.2013.02.003.

[20] K. Emara, W. Woerndl, and J. Schlichter, “CAPS: Context-aware privacy scheme for VANET safety applications,” Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks, WiSec 2015, 2015, doi: 10.1145/2766498.2766500.

[21] J. Freudiger, M. Raya, M. Félegyházi, P. Papadimitratos, and J.-P. Hubaux, “Mix-zones for location privacy in vehicular networks,” Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Wireless Networking for Intelligent Transportation Systems (WiN-ITS 07), 2007, [Online]. Available: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.83.1272&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[22] U. Computing, “CLPS: context-based location privacy scheme for VANETs Ines Khacheba *, Mohamed B . Yagoubi and Nasreddine Lagraa Abderrahmane Lakas,” vol. 29, 2018.

[23] F. Zidani, F. Semchedine, and M. Ayaida, “Estimation of Neighbors Position privacy scheme with an Adaptive Beaconing approach for location privacy in VANETs,” Computers and Electrical Engineering, vol. 71, no. December 2017, pp. 359–371, 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.compeleceng.2018.07.040.

[24] P. K. Singh, S. N. Gowtham, T. S, and S. Nandi, “CPESP: Cooperative Pseudonym Exchange and Scheme Permutation to preserve location privacy in VANETs,” Vehicular Communications, vol. 20, p. 100183, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.vehcom.2019.100183.

[25] I. Saini, B. St. Amour, and A. Jaekel, “Intelligent adversary placements for privacy evaluation in VANET,” Information (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 9, 2020, doi: 10.3390/INFO11090443.

[26] L. Benarous, S. Bitam, and A. Mellouk, “CSLPPS: Concerted Silence-Based Location Privacy Preserving Scheme for Internet of Vehicles,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 70, no. 7, pp. 7153–7160, 2021, doi: 10.1109/TVT.2021.3088762.

[27] M. Babaghayou, N. Labraoui, A. A. A. Ari, M. A. Ferrag, L. Maglaras, and H. Janicke, “Whisper: A location privacy-preserving scheme using transmission range changing for internet of vehicles,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 1–21, 2021, doi: 10.3390/s21072443.

[28] J. Huang, Y. Qian, and R. Q. Hu, “A Privacy-Preserving Scheme for Location-Based Services in the Internet of Vehicles,” Journal of Communications and Information Networks, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 385– 395, 2021, doi: 10.23919/JCIN.2021.9663103.

[29] I. Saini, S. Saad, and A. Jaekel, “A comprehensive pseudonym changing scheme for improving location privacy in vehicular networks,” Internet of Things (Netherlands), vol. 19, no. July 2021, p. 100559, 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.iot.2022.100559.

[30] M. Mushtaq et al., “Anonymity Assurance Using Efficient Pseudonym Consumption in Internet of Vehicles,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 1–17, 2023, doi: 10.3390/s23115217.

[31] C. A. Kerrache, C. T. Calafate, J. C. Cano, N. Lagraa, and P. Manzoni, “Trust Management for Vehicular Networks: An Adversary-Oriented Overview,” IEEE Access, vol. 4, no. c, pp. 9293–9307, 2016, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2645452.

[32] J. Petit, F. Schaub, M. Feiri, and F. Kargl, “Pseudonym Schemes in Vehicular Networks: A Survey,” IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 228–255, 2015, doi: 10.1109/COMST.2014.2345420.

[33] J. B. Kenney, “Dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) standards in the United States,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 1162–1182, 2011, doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2011.2132790.

[34] R. Adrian, S. Sulistyo, I. W. Mustika, and S. Alam, “A controllable rsu and vampire moth to support the cluster stability in vanet,” International Journal of Computer Networks and Communications, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 79–95, 2021, doi: 10.5121/ijcnc.2021.13305.

[35] L. Zhu, C. Zhang, C. Xu, X. Du, N. Guizani, and K. Sharif, “Traffic Monitoring in Self-Organizing VANETs: A Privacy-Preserving Mechanism for Speed Collection and Analysis,” IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 18–23, 2019, doi: 10.1109/MWC.001.1900123.

[36] K. Emara, W. Woerndl, and J. Schlichter, “Vehicle tracking using vehicular network beacons,” 2013 IEEE 14th International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks, WoWMoM 2013, 2013, doi: 10.1109/WoWMoM.2013.6583473.

[37] K. Emara, W. Woerndl, and J. Schlichter, “Beacon-based Vehicle Tracking in Vehicular Ad-hoc Networks,” Technische Universität München, Institut Für Informatik, pp. 1–22, 2013, [Online]. Available: http://mediatum.ub.tum.de/attfile/1144541/hd2/incoming/2013-Apr/691293.pdf

[38] C. Díaz, S. Seys, J. Claessens, and B. Preneel, “Towards measuring anonymity,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 2482, pp. 54–68, 2003, doi: 10.1007/3-540-36467-6_5.

[39] D. Krajzewicz, J. Erdmann, M. Behrisch, and L. Bieker, “Recent Development and Applications of {SUMO – Simulation of Urban MObility},” International Journal on Advances in Systems and Measurements, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 128–138, 2012, [Online]. Available: http://elib.dlr.de/80483/

[40] A. Varga and R. Hornig, “Omnetpp40-Paper.Pdf,” 2008.

[41] K. Emara, “PREXT: Privacy Extension for Veins VANET Simulator”.

[42] C. Sommer et al., Veins: The open-source vehicular network simulation framework. 2019. doi:

10.1007/978-3-030-12842-5_6.