IJCNC 05

SECURITY CULTURE, TOP MANAGEMENT, AND TRAINING ON SECURITY EFFECTIVENESS: A CORRELATIONAL STUDY WITHOUT CISSP PARTICIPANTS

Joshua Porche1 and Shawon Rahman2 1Information Security System Engineer, Melbourne, Florida, 32940, USA 2Professor, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Hawaii-Hilo Hilo, Hawaii 96720, USA

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to analyze the relationships between four variables (predictive constructs of top management, awareness and training, security culture, and task interdependence) and an information program’s security effectiveness. The difference between this study and previous research is the exclusion of information technology (IT) security professionals with Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) certifications. In contrast, participants in previous research were IT professionals with CISSP certifications. The research question asked to what extent is there a statistically significant correlation between each of the four predictive constructs and security effectiveness. This study made the same correlational determination between the independent variables and the dependent variable construct using a study population of 155 Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) members. This study used structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques to analyze relationships. The same previously used instruments were reused to reassess these particular participants. The results of SEM revealed that there was a significant relationship between security culture and security effectiveness. Similarly, significant relationships were found between top management, awareness and training, security culture, and security effectiveness, which repeated similar findings from previous research. A post hoc test was conducted using path analysis to reaffirm the direct causal relationship between security culture and security effectiveness that was also previously researched with similar results. The results demonstrated that security culture is a significant influence regardless of the participants’ perception of a security professional with or without CISSP certification. The implications of this can greatly affect reorganizational structure changes focused on developing security culture as an investment and a muchtargeted construct focused on by future researchers. This could result in human departments or functional managers realigning staff positions to concentrate on spreading security culture among fellow employees who affect cybersecurity either directly or indirectly in the workplace.

KEYWORDS

Security Effectiveness, Security Culture, Security Awareness, Security Training, Security Management, Task Interdependence.

INTRODUCTION

The present work investigates the key principles needed to address security management’s inability to thwart costly security breaches in organizations. This study examines the extent to which task interdependence (TI), top management support (TM), awareness and training support (AW), and security culture (SC) are positively associated with information security program effectiveness (EF) without participants with Certified Information Systems Security Professional

(CISSP) certifications. This study compares the results from a previous study that examined the same relationship but with CISSP certifications [1]. Earlier research revealed a significant direct relationship between three of the abovementioned independent variables (SC, TM, and AW) and the dependent variable (EF).The population sample of Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] survey consisted of participants who were from a security professional organization known as the International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium (ISC2). This professional organization encompasses a commonly accepted professional security certification referred to as the CISSP certification. This paper attempts to apply the same survey instrument used by Knapp and Ferrante [1] to be administered to the information technology (IT) organization referred to as the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA). The difference in the population type was purposeful to capture the opinions of a lesser security-bias population of IT security professionals who do not have CISSP certifications. First and foremost, the intent is to observe the same constructs and relationships in common, i.e., SC, TM, and AW, and whether they remain significant positive contributors toward EF. Subsequently, the remaining independent variable from the list of constructs mentioned (e.g., TI) would be further analyzed for its direct relationship to EF. The previous study was analyzed in Knapp and Ferrante [1] using ISC2 participants with CISSP certifications.

This study was analyzed similarly, but with a new targeted population of participants (i.e., ISACA members with IT security experience instead of ISC2 members with CISSP certifications). This research responds to a limitation identified from the previous research presented by Knapp and Ferrante [1] to analyze further a less biased opinion from participants who did not possess a CISSP. Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] original intent was to analyze the moderating effects of TI to determine if it affected all remaining construct relationships involved within the model. However, for this study, the objective was to analyze and focus on whether all constructs had a direct relationship to security effectiveness (EF) as a priority given the change in participant selection for non-CISSP participants. Due to the limitation in the quantity of sample selection, the analysis on the moderation of TI was omitted for this study. Still, the direct relationship from TI to EF was uniquely analyzed for this study following a standard confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) during the structural equation modeling (SEM) process.

LITERATURE REVIEW

This literature review addresses previous research on the topic of EF and related constructs that are relevant to this study. The problem at hand concerning cybersecurity is discussed, and the means of conducting this research is covered. The theoretical orientation and models related to EF are studied and analyzed. This chapter covers the constructs that affect EF and those that make up the model associated with EF. This model includes constructs such as TM, AW, SC, and TI (where relevant to EF). Moreover, the opinions on increasing EF from the perspective of IT security professionals with CISSP certifications will be analyzed with respect to opinions derived from IT security subject matter experts without CISSP certifications.

2.1. Background

The overall topic of this study pertains to the ineffectiveness of security defense measures in organizations to thwart attacks from cybercriminals, inadvertent user attacks, and foreign adversaries on organizations overseas to reduce the aspects that make such organizations vulnerable. The organizational structure that is aligned with security management practices must be addressed to mitigate these vulnerabilities. Cyber defense lags behind hackers, as adversaries remain one step ahead of updated vulnerability patches ([2]; [3]; [4]; [5]). The lag can be addressed by looking into the structure of an organization and what critical elements can be used

to promote security. If this lag can be addressed via organizational structure, then the necessary management styles can be adopted for processes so that they can improve cyber defenses for our sensitive gamut of concerns. These concerns range from financial, health, and sensitive data to other data that must not be compromised by any stakeholders without potential loss of life, threats to national defense, or compromising any sensitive data.

2.2. Top Management Involvement

The repercussions of a lack of cybersecurity can be a matter of safety and health of human beings. According to Martin et al. [6], cybersecurity in healthcare requires top managers of policies to compensate for the lack of governance. Therefore, control from an organization can be obtained when management that is onsite and engaged is involved in an organization’s security posture. A management strategy is needed to keep pace with hackers who have an ongoing strategy in place.

Hackers observe security management behaviors across the industry for weaknesses. According to Rideout [3], patch management is one-way hackers can investigate what platforms or applications are vulnerable because patches are observed traversing across the internet, allowing cybercriminals to see where exploits may exist. It is a good idea to patch unknown vulnerabilities on your system; however, it is terrible news that every hacker observing updates can tell where vulnerabilities lie in unpatched systems. This dichotomy reveals that hackers continuously remain a step ahead whether in healthcare, government, or any other area where such IT equipment and software are used.

In the same manner that hackers affect the healthcare industry, it has also affected the legal industry. Approximately one-quarter of firms with at least 100 attorneys have had data breaches within their organization [4]. If the lack of defense results in these wide spread attacks across a multitude of industries, then some evaluation of processes must take place to investigate management breakdowns. Despite Choi et al.’s [6] notion of management policies being a solution to cyber security, the implementation method matters just as much as adding methods to help reduce the risk of attacks and thus produce effective security.

Organizations have to seek other means of dealing with cybersecurity from a management perspective. According to Woods et al. [5], cyber insurance has become a popular means of dealing with breaches as an answer by many organizations to deal with the risk of cyberattacks.

2.3. Culture Involvement

The need for cybersecurity involves many different constructs that are related to security. The key constructs that have been researched and have an impact on EF are TI, SC, TM, and AW [1]. While culture could be a major factor in an organization to find answers to address organization or employee cyber-EF, its impact can be direct in some cases and indirect in others.

Security effectiveness can be impacted by SC, even if indirectly so. According to Chen et al.[7], there is a relationship between information security projects and SC. Injecting specific processes that enhance SC would affect security in an organization. Da Veiga [8] also pointed out that security policy can lead to an influential SC that can affect employees’ ability to reduce risky behavior. An employee’s misguided behavior, whether intentional or unintentional, can eventually lead to cyber incidents.

Major breaches can appear because of either intentional or unintentional user behavior, and so the source of this is just as important to understand in either situation. In some studies, 80% of security faults resulted from user behavior [9]. Getting to the root of the problem means

understanding where the lack of ignorance that leads to this unintentional misuse originates; bad behavior warrants further analysis. A better look into the mindset of end-users or employees is needed. Some companies try to address cyber attacks via administrative means, but research has concluded that an organization’s mindset must be part of the equation [10]. The ability to address this mindset using improvements in SC may help thwart security faults attributed to bad behavior. Incorrect decisions may come from a lack of training or positive SC.

Un intentional behavior can affect security just as significantly, especially from untrained users. An employee’s bad decisions can lead to a breach; for example, all it takes is one wrong decision to click a link that looks purposeful yet is actually a planned and targeted phishing attack [10]. If accidental actions from a user or employee can yield cyberattacks, this behavior could be attributed to a lack of suitable training or culture which can have an effect on compliance [11]. There are social issues other than technical ones that affect EF, hence the STS theory mentioned earlier as a driver of this research

Security technical solutions are important, but culture also plays a part in the final outcomes. According to Tang and Zhang [12], employees’ consciousness regarding security can be a critical attribute to cause losses in companies due to humans setting a low priority for security. There appears to be a greater cyber threat when there is a lack of employee consciousness concerning security; this has nothing to do with the security tools being applied to thwart attacks; rather, it has to do with behaviors that can contribute to breaches.

Human behavior plays a key role in whether an organization is at risk of a breach; this role is of the same importance as the technical tools used to thwart hackers. According to Connolly et al. [13], the technical means to defend against a breach have no effect on the human behaviors that increase the risk of a breach. Specialized tools cannot prevent decisions by users or customers to irrationally share sensitive documents, capture images, or insert USB devices in inappropriate areas. Adjusting these behaviors can be done by improving the culture in an organization or firm for the benefit of creating a more secure environment.

Curbing SC helps steer firms toward better security performance. According to Zailani et al. [14], management is effective in improving security performance when SC is improved. If SC can enhance management’s ability to affect security, then an element of training should be employed to enhance organizations’ and firms’ SC in the workplace. The flaws found within user behavior present risks to security.

Users are more affiliated with social networks, and as a result, a user’s behavior can put their company at risk. According to Steinmetz and Gerber [15], irresponsible behavior by users in what they choose to share brings a heightened risk of security in to the workplace. User behavior is part of the culture that needs to be corrected through training, so users can be made aware of the attack vectors they can create by sharing information on social networks. Unexpected behavior is an attribute that is monitored to see patterns outside the norm.

If there are expected ways in which a host should utilize information systems, then unexpected behavior can and should be monitored. According to Ullah et al. [16], a host’s behavior can be patterned and measured to see if it deviates from the pattern norm and, as a result, generate alerts. If this can be measured for each host, then training users on their practices would benefit IT security by monitoring and tweaking training where there are deviations from the norm. This is another reason SC matters and requires training to convey to users and employees what is expected in terms of behavior. When bad behavior is conducted, it has to be untrained users or purposeful actions that warrant investigation.

One bad act by one employee can cripple an entire organization. Technology alone cannot protect a firm. According to Zelle and Whitehead [17], a single employee can make one alteration to a financial record that could be a financial disaster for the whole organization. Since technology alone cannot be the only layer of protection, culture must be an additional protection layer since bad cultural behavior can result in catastrophic breaches

2.4. Awareness and Training Involvement

Training needs to be considered as a counter to improving SC. According to Evans et al. [18], human error a lone is not the weakest link in organizational security but remains a culprit today in terms of the reasons for security breaches. If training can improve SC, then breaches should be reduced. Training programs are another construct that must be assessed and analyzed as an attribute that can make a significant difference in EF

Security training can not only impact the users of IT but also positively impact information security specifically. According to Chin et al. [19], more productive security training affects perception and increases both security understanding and protection against security risk. If it has a positive impact, then it should be uniform across the industry and para mount to affecting EF within an organization. An essential attribute to security training is user security awareness.

Users are on the front line of an organization’s infrastructure. Users are also direct inputs for IT. According to Bostan [20], user awareness is a crucial component that results in security breaches and is always vulnerable to user misuse of a system. If given a preference regarding security workarounds, Farcasin and Chan-tin [21] found that users tend to undermine security by choosing the path of least resistance when it comes to using strong passwords rather than using simpler ones or even taking longer periods to change their passwords instead of doing so frequently. Therefore, the tendency is for users to choose convenience over security. Training is needed to make users aware of such risks to organizational data.

Training should be geared toward the most damaging form of cyberattack that affects both users and their organizations. A phishing attack is about deception to get a user to reveal in formation, and it usually takes less than 2 minutes after an attack is initiated for the first victim to succumb; however, user training against phishing attacks has proven effective (Iuga et al., [22]). If cyberattacks are continually evolving, then training must keep pace continuously, as methods of deception are everchanging to keep up with the latest technology and trends. Despite the hacker’s involvement, user misuse can still be just as damaging

Training helps reduce the chance of unforeseen actions by users due to untrained actions.

According to Mahlaola and Van Dyk [23], without proper training, most security breaches were a result of unintentional steps made out of ignorance. Training should have a certain degree of impact on improving security or reducing the risk of a breach if it can lessen unintentional user mishaps. Someone in leadership should oversee ensuring that training is being applied to help reduce mishaps in the same manner as more technical implementations for cyber defenses against cyberattacks

Training cannot just be an annual event that has no long-term learning effect on users. Training must be given and assessed using metrics to ensure that it affects information systems in terms of aspects such as surveys, procedures, and bench marks (Scholl et al.,[24]). If training is taken sufficiently seriously to where its effectiveness can be measured, then this should be a standard approach to all organizations approaching the reduction of security exploits and breaches using a training program.

2.5. Task Interdependency and Collaborative Tasking

TI could either contribute to or reduce EF other than solely relying on top management, training, and SC. TI refers to the extent to which members of a team are dependent upon one another to complete tasks (Medina & Srivastava [25]). Research has revealed that TI is a significant influence and impacts effectiveness in that leaders should align a certain amount of TI with a team’s goal (Li et al., [26]). If EF is the team’s goal, then collaboration and interdependency to achieve that goal impacts EF (i.e., one person alone may not be able to aid EF within their group). Further more, methodologies that traditionally work together collectively may benefit (e.g., Agile Scrum projects) as opposed to those that work less well collectively (e.g., waterfall).

Agile Scrum and waterfall methodologies may respond to improvements in EF differently because TI for one may be higher than for the other. According to Medina and Srivastava [25], teams’ interactions (e.g., methods of communication) may also impact their effectiveness. According to Santos et al. [26], TI can even change team creativity. Some of the process methodologies that different teams use may cause different interaction methods. Overseas teams ’IT industries may have changed or customized their ways, making their teams’ outputs different to each other’s based upon their team makeup and collaborative nature.

Security effectiveness could differ as a measured output based upon the different team dynamics and any other potential unseen variables . According to Nebel et al [27], an increase in TI leads to an increase in both collaboration and overall performance as experimented in games. If there is an increase in performance in games and there is a common objective for a team to have increased EF, then one could reason that as long as a team collaborates effectively, then there could be some expectation of an increase in EF. TI’s key variable within could be a close collaboration factor.

Close collaboration is a crucial input variable needed for TI to influence team performance. According to Horstmeier et al. [28], TI allows for diverse climates to enable an increase in team performance. If an organization has a culture of close collaboration and leaders strive to invoke that in their culture, then the benefit of close collaboration should reveal itself in the objective. Further more, if that objective is EF, then leadership and training should create that kind of environment for their teams within the organization. This social dilemma of leadership and trainers creating an atmosphere of collaboration needs to be accepting of necessary technological measures alongside any communicative coupling to further emphasize the notion of STS theory mentioned earlier for this research’s aligned theory.

2.6. Social and Technical System Theory

The underlying theory for this study is the STS theory, which is derived from general systems theory [29] that consists of two different types of linked systems, i.e., a technical system and a social system. The social system is focused on values, skills, attitudes, values, rewards, organizational structure, and the technological system is focused on technically necessary processes and tasks for the proper desired outputs [30].

The social aspects of an organization can feed into the outputs of an organization’s processes, just as the technical operations involved in that same organization influence technical issues that need correction using technological means. According to Malatji et al. [31], both social and technical components are subject to an organization’s operational environment.

Subsequently, STS systems could be tailored to influence certain operations that need improvement. Directing improvement in industrial systems or organizations with technical issues

could be fine-tuned using a combination of social and technical components, for example, organizational structure, training, culture for social aspects and technical training, and proper technical training acquisitions in the technical aspects for STS.

In addressing the risk of cyber espionage, adding technology to resolve a technical issue without accounting for human factors as a significant negative influence could result in money spent without the desired output. Humans operate machinery and network devices; therefore, there is an element of direct or indirect influence that must be considered. According to Ceesay et al. [32], technical solutions will prove insufficient unless the structure is applied to human involvement. People’s roles in operating technology are a necessary additive to reduce bad habits. It was further pointed out that proactive management is a critical element for decreasing the risks associated with cyber espionage [33].

STS principles can be applied to the overall improvement in large industries and organizations looking for a turnaround in performance and in critical areas of improvements related to social inputs within the company attributed to causing low performance. Coca-Cola applied STS principles when trying to turn the company performance around from inferior compared to its counterpart Pepsi, who were performing tremendously better. Coca-Cola recovered from a 26% reduction in share price to a 25% increase by applying principles originating from the STS referred to specifically in this case as the North American Open Sociotechnical System (NAOSS), the system previously known as Taylorism. In this case, getting employees to self-desire to carry on tasks also self-obtains the ability to carry out tasks [33]. Self-motivating employees who carry out specific necessary tasks could be duplicated in any effort for technical points of contact to carry out technical tasks to solve technical issues (e.g., they could be cyber-related or machineryrelated). An element of leadership and culture aids more in the desired goal of improving technically associated metrics.

Preventing cyberattacks on organizations will require both social and technical approaches that consider the location, people, and equipment. According to Malatji et al. [31], preventing ransomware or Stuxnet-type cyberattack scenarios requires more than just monitoring technical components; rather, social components related to the work environment must be supervised. Monitoring cybersecurity techniques is still pivotal to combating cyber attack threats but should include the same effort level for the social dimension[31].

Technologies that incorporate automated systems are not sufficient to dismiss the need for social components when implementing network-centric systems to improve performance. Healthcare industries have found that automated systems are unsuitable for incorporation in healthcare information systems. Enforcing STS could properly implement and enhance legacy systems for the intended real-time data entry originally sought in healthcare information systems when leveraging users for input to improve the system [34]. Suppose that automated systems are set up incorrectly or administered ineffectively for end-users; in that case, social components need to be researched and investigated to improve the equipment’s capacity to solve problems. This very idea of social components affecting users and technical operators to allow for obtaining necessary objectives demonstrates that the STS theory is a fundamental approach to fine-tuning desired outputs given the environment from which the technical issues were arising.

This study confirms what social aspects can impact technical issues needed to output a positive program EF metric. Additionally, it reinforces different scenarios of social influence that moderate different types of outcomes [35]. This study analyzes how organizational structure changes can improve quality [36] in EF. The theoretical implication is that the social effects of TM, AW , SC ,and TI influence EF. The impact of each construct on overall information EF will lead to management tailoring organizational structures to enhance EF [1].

2.7. CISSP vs Non-CISSP

It is advantageous to obtain advice from subject-matter experts on security regarding improving cybersecurity programs. CISSP is a crucial certification for identifying security professionals with critical skills required to better understand security managers and their organizations. They are responsible for effective management, especially given the required 5 years of security experience to take the exam[37]. Such influencers of cybersecurity are in catch-up mode when trying to thwart or deal with cybersecurity vulnerabilities and threats. Just as many talented and skilled cyber leaders have prestigious CISSP certifications, there is further talent abroad in other key subject-matter experts whose job influences EF without obtaining a CISSP certification. Therefore, we cannot assume that the pipeline of security managers and others whose key roles are to improve EF are limited solely to those with CISSP degrees. Non-CISSP Certifications

IT professionals abroad do not all have CISSP certifications. As a result, there is a discrepancy between the need for CISSPs and those who currently hold key positions without those certifications represent a vast majority of maintainers. According to Furnell [38],there is a shortage of CISSP certifications and constantly increasing demand. As a result, organizations can miss the diverse IT professional pool of talent due to the assumption that only members with CISSP inputs matter, thereby overlooking a collection of technical skills that can help find solutions to flaws in EF. Key roles across the industry related to security have significant roles in IT infrastructure. These roles are vital and different from those solely dedicated to security (e.g., design engineers, software designers, and system integration and test engineers).

Cyberbreaches have proven rampant and expensive across the entire IT industry and a danger to everyone’s national security and privacy. There is a need for EF to thwart cyberbreaches. Studies have shown that invoking proper leadership, training, and culture can help curb such results if applied correctly. This is a problem requiring neither a solely technical nor process-related solution. This problem needs a holistic approach that is both social and technical as prescribed by STS theory. One major proven contributor to success when applying such constructs is an environment within the organization in which members are reliant on each other, i.e., assessed as having a high TI. A more collaborative team structure could be the first step to preparing organizations for drastic leadership-, training-, or culture-improvement processes that are focused on security breach risk reduction strategies. High TI alone does not equate to EF unless users’ behaviors in the form of training and in both the culture and leadership that motivate policy adherence take place. Moreover, the diverse pool of users requires collaboration among those users to conclude what is best for the organization other than just security personnel with CISSP certifications. The assessment of Knapp and Ferrante [1] links TM, AW, high TI, and some added moderation from SC toward improved measured EF. This should be reassessed among a broader and less-biased group of security professionals and more diverse pool of IT professionals to properly test whether other major players within the SDLC assess the same results regardless of security bias.

Improving SC may be a central goal for information security programs, and if it can be further enhanced using AW, then training should be analyzed within an organization to see where it can be better applied. If leadership strategies that involve management, training, and culture improvements can be leveraged for the sake of improving cyber security, then that allows for an effort worth implementing across the industry. Vulnerabilities are a standard technical metric that needs to be assessed and addressed. The STS theory of combining a hybrid solution of both technical and social means to improve EF can be applied but should be evaluated to see if correlations between the independent variables TM, AW, TI, and SC correlate significantly with

EF as Knapp and Ferrante [1] demonstrated when CISSPs were assessed for these same construct measurements. The next section discusses the materials and methods used to conduct this study

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research uses a non experimental correlational quantitative design. The survey instrument is a 5-point Likert scale designed by Knapp and Ferrante [1] to assess the independent variables of TM, SC, AW, and TI along with the dependent variable EF. This survey instrument derived by Knapp and Ferrante [1] was emailed to IT professionals (ISACA members who were purposely excluded if they had a CISSP certification). The participants were filtered to have at least a bachelor’s degree, be a member of ISACA, not have a CISSP certification, and have obtained at least 5 years of IT security experience as a demographic criterion before participation in the survey. The research was intentionally in contrast with previous research that used IT professionals with CISSP certifications. This exclusion was to avoid any potential bias as suggested by earlier research results as a possible extension or gap pointed out in the research that needed to be examined [1].

SEM was conducted in previous research and is utilized in this research to capture the following measurements of each of the relevant construct’s indicators (e.g., standardized factor loading, critical value (z-statistics), and SMC) [1]. Additionally, the means, standard deviations, zero correlation, and alpha values are measured and displayed for each of the five constructs [1]. Partial mediation analysis follows measuring the coefficients and fit indices per the SEM considering and displaying all relevant path models and their corresponding goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [1]. For the purposes of a potential post hoc analysis, an additional analysis using repeated SEM is conducted to analyze high and low TI conditions for later comparisons where it is most economically feasible. To administer this post hoc analysis, there is a definition of high TI vs. low TI using a quartile approach, i.e., the top 27% represents high TI vs. the bottom 26% [1]. The confirmation or rejection of the hypotheses is based upon the completed results of CFA. Depending on the results of the CFA, an additional post hoc analysis is conducted to measure any relevant high vs. low TI affecting EF and potentially other constructs. Figure 1 outlines the flow of the research design mentioned in this section.

3.1. Research Questions and Hypotheses

Four research questions were investigated during this study. The research questions were answered by testing null and alternative hypotheses as follows:

Research Question 1: To what extent is TM significantly correlated with EF?

- H01: There is no statistically significant correlation between TM and EF

- Ha1: There is a statistically significant correlation between TM and EF

Research Question 2: To what extent is AW significantly correlated with EF?

- H02: There is no statistically significant correlation between AW and EF

- Ha2: There is a statistically significant correlation between AW and EF

Research Question 3: To what extent is SC significantly correlated with EF?

- H03: There is no statistically significant correlation between SC and EF.

- Ha3: There is a statistically significant correlation between SC and EF.

Research Question 4: To what extent is TI significantly correlated with EF?

- H04: There is no statistically significant correlation between TI and EF.

- Ha4: There is a statistically significant correlation between TI and EF.

3.2. Instrumentation

The survey instrument mentioned is the culmination of five different constructs from a total of 26 indices that were to be reassessed based on ISACA member responses. The final questionnaire used by Knapp and Ferrante [1] to measure TM, AW, SC, TI, and EF was answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Responses were recorded as 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

3.2.1. Survey Instrument Questions

These questionnaire points used in this study that originated from Knapp & Ferrante’s [1] Instrument are as follows:

- Top Management

a) Q1. Top management considers information security an important organizational priority.

b) Q2. Top executives are interested in security issues.

c) Q3. Top management takes security issues into account when planning corporate strategies. d) Q4. Senior leadership’s words and actions demonstrate that security is a priority.

e) Q5. Visible support for security goals by senior management is obvious

f) Q6. Senior management gives strong and consistent support to the security program

2.Awareness & Training

a) Q7. Necessary efforts are made to educate employees about new security policies.

b) Q8. Information security awareness is communicated well.

c) Q9. An effective security awareness program exists.

d) Q10. A continuous, ongoing security awareness program exists.

e) Q11. Users receive adequate security refresher training appropriate for their job function.

3. Security Culture

a) Q12. Employees value the importance of security.

b) Q13. Security has traditionally been considered an important organizational value.

c) Q14. Practicing good security is the accepted way of doing business.

d) Q15. The overall environment fosters security-minded thinking.

e) Q16. Information security is a key norm shared by organizational members.

4. Task Interdependency

a) Q17. I have a one-person job; I rarely have to check or work with others (reverse coded).

b) Q18. I have to work closely with my colleagues to do my work properly.

c) Q19. In order to complete our work, my colleagues and I have to exchange information and advice.

d) Q20. I depend on my colleagues for the completion of my work.

e) Q21. In order to complete their work, my colleagues have to obtain information and advice from me.

5.Security Effectiveness

a) Q22. The information security program achieves most of its goals.

b) Q23. The information security program accomplishes its most important objectives.

c) Q24. Generally speaking, information is sufficiently protected.

d) Q25. Overall, the information security program is effective.

e) Q26. The information security program has kept risks to a minimum.

The next section explains the reliability and validity of the survey instrument.

3.2.2. Validity and Reliability

All loadings were found to be statistically significant and above the 0.707cutoff criterion to support convergent validity. Additionally, to support discriminant validity, all items were loaded on the targeted factor with no cross-loading. The loadings were statistically significant and higher than .707. The chi-squared delta between constructs demonstrated significant differences (p < .001) [1]. Cronbach’s alpha (α) reliabilities for each construct were as follows:

- The EF construct assessed by a six-item Likert scale had an alpha value = 0.91

- The TM construct evaluated by a five-item Likert scale had an alpha value = 0.93

- The AW construct evaluated by a five-item Likert scale had an alpha value = 0.93

- The AW construct evaluated by a five-item Likert scale had an alpha value = 0.93

- The AW construct evaluated by a five-item Likert scale had an alpha value = 0.93

For the proper assessment of the constructs referred to as EF, SC, TM, AW, and TI, the overall instrument was reused as it had been administered by Knapp and Ferrante for all survey questions with no changes or alterations; however, it must be noted that Knapp and Ferrante themselves excluded two of the seven TI questions, as they were not in the Likert scale format. Furthermore, it must be noted that Knapp and Ferrante validated that this modification did not affect the proper internal reliability. Knapp and Ferrante standardized the seven survey questions prior to combining them as a single measurement. With this appropriate deviation of two of the seven survey questions, the internal reliability had been calculated by Knapp and Ferrante[1] to be a suitable internal reliability level (α = 0.75) in comparison with the original internal reliability measured (α = 0.79).

3.2.3. Sampling

The sample size sought out was calculated from a G*Power calculation result of 116 members given an effective size of 0.3, an alpha of 0.05, and a confidentiality value of 95%. The sample size was based upon a G*Power calculation that showed a minimum of 45 for multiple regressions and 133 needed for chi-squared tests as depicted in the power analysis section. This also aligns with the rule of thumb of N =100–150 (Wang & Wang, [39]). The targeted sample size for this research resulted in a successfully acquired sample size of 150.

G*Power calculation was conducted and resulted in the following statistical calculations (Figure 2) to produce the sample size needed to achieve the research purposes. Economic considerations were given to properly aim for the most efficient means for obtaining the needed sample of respondents for this research

Figure 1. G*power Sample Size Calculation

3.3. Data Analysis

The data collected by Qualtrics were responses to a 26-item questionnaire that used a 5-point Likert scale [1]; this 26-item questionnaire encompassed the independent constructs representing TM, SC, AW, and TI and the dependent construct of EF. One hundred and fifty targeted responses resulted in the capturing of the five constructs mentioned in this research as inputs for SPSS for further analyses. A confirmatory analysis was conducted to verify any direct or indirect correlations between constructs to repeat analysis efforts under taken by Knapp and Ferrante[1]. In addition to the confirm atory analysis, a path analysis (PA) was conducted to complete the SEM analyses and to measure any direct relationships to test the hypotheses.

The data collected by Qualtrics were responses to a 26-item questionnaire that used a 5-point Likert scale [1]; this 26-item questionnaire encompassed the independent constructs representing TM, SC, AW, and TI and the dependent construct of EF. One hundred and fifty targeted responses resulted in the capturing of the five constructs mentioned in this research as inputs for SPSS for further analyses. A confirmatory analysis was conducted to verify any direct or indirect correlations between constructs to repeat analysis efforts under taken by Knapp and Ferrante[1]. In addition to the confirm atory analysis, a path analysis (PA) was conducted to complete the SEM analyses and to measure any direct relationships to test the hypotheses.

4.RESULTS

The following section describes the research questions, hypotheses, and discoveries from the post hoc test analyses. Finally, the results will summarize the findings based on the data collected and the statistical analysis applied while orienting the reader toward the discussions, implications, and limitations that will be discussed in Section 5.

The following section presents the results of the study and briefly discusses what they mean for the field. The section is divided into three sections. The first section looks at the demographics of the respondents to the study. The next section looks at the preliminary analysis and how the variables met normality. The last section discusses more thoroughly the data analysis and the results of the study.

4.1. Demographics and Statistics

These demographic criteria were targeted via Qualtrics. No additional demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, race, nationality) were needed for this study. Additional data were captured to gather the type of department in which the respondent was working. Other data were gathered to better understand whether a respondent worked in an Agile, a non-Agile, or a different development type of methodology for the purposes of any potential future research or

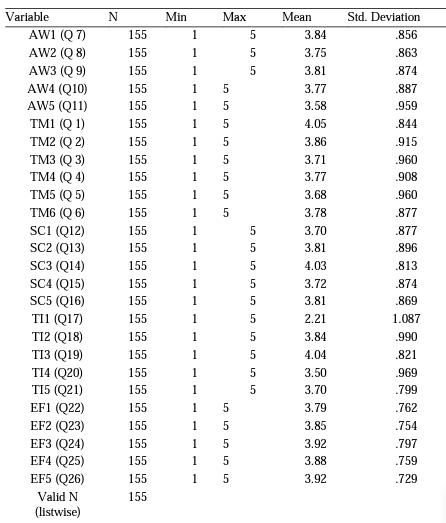

inferences that could be studied. This additional data can be found in Table 2, which shows a frequency table for nominal data. All data collected was stored on secure servers as part of standard secure data-gathering procedures. If warranted, data would only be retrievable via password-protected devices. All data were gathered and stored in an anonymous format barring any traceability to respondents. The data were imported into AMOS 26 and Intellectus Statistics [42] software in an SPSS format to be analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis and PA SEM techniques within this research study’s scope. The 26 questions that used a 5-point Likert scale were responded to by 155 survey participants. The 26 indicators representing the 26 survey questions included in this study were coded and imported into SPSS. The descriptive statistics showing the min, max, mean, and standard deviation of each item resulting from the respondents’ replies are as follows (see Table 1):

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Mean and Standard Deviation for the 26 Survey Questions

The most frequently observed category of Q43 in relation to the current department category of the respondent was IT (n = 151, 97%). The most frequently observed category of Q47 in relation to the system development methodology category was Agile-like (e.g., Scrum, Kanban) (n = 61, 39%). The most frequently observed category of Q46, in relation to the education level, was a bachelor’s degree (n = 101, 65%). Frequencies and percentages are presented as follows (see Table2)

Table 2. Frequency Table for Nominal Variables for Additional Questions

Note. Due to rounding errors, percentages may not equal 100%

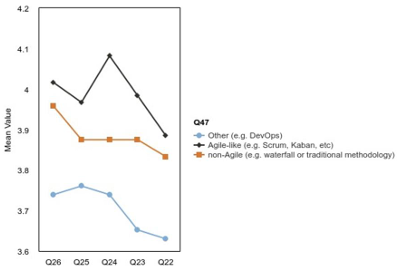

It should be noted that Figures 2 and 3 depict the types of survey responses regarding EF and SC constructs, respectively, in relation to Agile vs. non-Agile-like methodologies through which respondents were working for their organizations.

Figure 2. EF Plot of Agile-like Respondents

Figure 3. SC Plot of Agile-like Respondents

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

SEM analyses were conducted to determine whether the latent variables (AW, TM, SC, TI and EF) adequately described the data. Maximum like lihood estimations were performed to determine the standard errors for the parameter estimates.

The hypotheses were tested by conducting a CFA as a portion of the SEM using the same constructs from Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] model involving constructs referred to as TM, AW, SC, TI, and EF. The TM, AW, and EF constructs positively and significantly correlated with SC, with the exception of TI. The assumption to be able to conduct SEM, which includes a CFA, and the optional PA was based upon whether the model being analyzed was a good enough fit for further analysis of the model.

The following analysis and data are presented and combined for each hypothesis. The data were used to determine whether the hypothesis is supported or rejected.

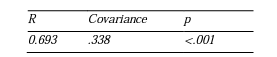

Hypothesis 1 (alt): There is a statistically significant correlation between TM and EF

A relationship between TM and EF was observed, and a correlation in dex was measured at .693. The corresponding covariances were found to be significant at p < .001, suggesting the association was significant. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected, and the alternative hypothesis was accepted. Table 3 shows the significance threshold of the covariance measurement and the extent of the estimated correlation following the data analysis

Table 3. https://ijcnc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/tab1234.png

Hypothesis 2(alt): There is a statistically significant correlation between AW and EF

There was a positive relationship observed between AW and EF, and a correlational index measured was .650, p < .001, suggesting the association is significant. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected, and the alternate hypothesis was accepted. Table 4 shows the significance threshold of the covariance measurements and the extent of the estimated correlation following the data analysis.

Table 4. Positive Correlation between Awareness and Training and Security Effectiveness

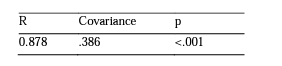

Hypothesis 3 (alt): There is a statistically significant correlation between the SC and EF.

A positive relationship was observed between SC and EF, and a correlational index measured. 878, p <.001, suggesting a significant correlation. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected, and the alternative hypothesis was accepted. Table5 shows the significance threshold of the covariance measurement and the extent of the estimated correlation following the data analysis.

Table 5. Positive Correlation between SC and Security Effectiveness

Hypothesis 4 (null): There is no statistically significant correlation between TI and EF.

There was a relationship observed between EF and TI, p was not <. 001, and a correlation measurement was observed to be .314, suggesting no significant correlation. Therefore, the null hypothesis was accepted, and thus, the alternative hypothesis was rejected. Table 6 shows the significance threshold of the covariance measurement and the extent of the estimated correlation following the data analysis.

Table 6. Positive Correlation between TI and Security Effectiveness

4.3. Full Analysis

Data from the respondents were collected and analyzed using AMOS and Intellectus Statistics to conduct SEM. The proper model fit was analyzed and was deemed sufficient based upon RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR fitness threshold standards. Following this sufficient determination of fitness using more than one fitness test, a CFA was further completed to further test the hypothesis for any covariances and correlations between the predictor constructs (TM, AW, SC, and TI) and their relationships with the dependent variable (EF). Although this wasonly one of the main objectives, a post hoc test followed by conducting PA in comparison to Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] previous study’s findings on direct causal relationships to EF. The overall detailed results of the data and all comparisons with the constructs during the SEM analysis as they relate to the tested hypothesis are discussed and summarized in Table 7 for findings that determined the summary of results for each hypothesis test.

Table 7. Summary Results of Correlation Data Analysis for the Hypotheses

Note: Correlation estimates* were based upon a Pearson equivalence exported from AMOS.

Following the determination of the significance between the construct relationships relevant to the hypotheses testing, other relationships that had correlations were observed. Additionally, PA was conducted, and direct causal relationships were studied and compared to previous research. The overall correlation interpretation and PA are presented or the benefit of further research and any assertions or support of past research.

There was a positive relationship observed between SC and AW with a correlation index of .74, p < .001, indicating a significant correlation. There was a positive relationship observed between SC and TM with a correlation index of.751, p <.001, indicating a significant correlation. There was appositive relationship observed between SC and TI, and a correlation index measured was .304, p > .001, suggesting no significant correlation. There was a relationship observed between AW and TI with a correlational index of .277, p > .001, suggesting the relationship was not significant. A relationship between TM and TI was observed, and a correlational index measured .234,p>.001,suggesting the relationship was not significant. These correlations were captured prior to the PA and demonstrate that the relationships observed outside of the hypothesis-related constructs show significant correlations between other predictors, i.e., AW and TM with SC.

The PA was conducted as a post hoc test activity and did result in three significant direct casual relationships. There were direct causal relationships discovered from the predictive constructs of

TM and AW. Both constructs individually resulted in a direct causal relationship to SC and were found to be significant. Additionally, the SC construct itself was found to have a direct causal relationship to the dependent variable (EF) in both this study and Knapp and Ferrante’s (2014) previous research.

4.4. Summary

One of the goals of this research was to investigate whether EF is significantly correlated with TM, AW, SC, or TI among respondents who were non-CISSP IT professionals who had been educated with at least 5 years of security experience. The results of this analysis showed that there is a positive and significant correlation that ranged from either large (0.5 < r < 0.7) to very large(0.7 0.001) between TI and EF. After the post hoc testing analysis, it was discovered that SC has a direct causal relationship to EF. Furthermore, it was revealed that both AW and TM constructs had a direct causal relationship with SC. Additionally, other correlations that involved SC were found to be significant, i.e., AW and TM. These findings are in line with Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] previous research. This also supports Knapp and Ferrante’s [1] earlier assertions that SC helps mediate other predictive constructs toward EF. The consistency between both this study and those by Knapp shows that the SC construct is a major influencer and is strongly correlated with EF. Further more, it was found to have a direct causal influence on EF. This was consistent regardless of the differences in the population selection. Section 5 entails further discussions, implications, and recommendations associated with these findings and those from previous research. The analysis results will be further explained by the research data collected and how we can apply these findings in the future. The possibilities for extending the research will also be discussed.

5.RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The ability to conduct SEM on past models concerning correlating constructs or direct causal effects on EF should further extend to other constructs impacting SC alone. It has been demonstrated that SC not only correlates significantly with other predictors (e.g., TM and AW), but also has a direct influence on EF. SC should be analyzed with other constructs, e.g., communication constructs [40]. Other similar constructs could be introduced from other models where SC has been studied. This could also include using other survey instruments to assess SC as a dependent variable. Different aspects should not be ignored, such as how a team interacts with each other during a software or system development lifecycle methodology, i.e., a construct where collaboration is strongly influenced (e.g., Agile scrum) or a leadership style is invoked (e.g., transformational leadership [41][43]. Teams in different development phases may have different opinions on SC, as groups tend to evolve from the good or bad based on familiarity and teamwork vs. meeting for the first time [44][52]. Consistent polling for participants from similar and dissimilar developmental phases might need to be considered to assess SC when popular methodologies are introduced properly. Teams working together in close-quarter environments (e.g., labs) could also be considered compared to remote environments where team members are not seen. Recent technical advanced cyber defense techniques i.e., machine learning approaches to defend against an increase attack vector from IoT devices that are popular [53]. These comparisons used would be a research opportunity to confirm if automation from machine learning contributes to an positive perception of security effectiveness given the reduction of complex manual configuration needed for cyber defense techniques without automation. Other considerations that could also be taken into account are whether IT teams are working on projects virtually or leveraging everything in an IT cloud environment.

Another target audience that could be assessed is system administrators. This core role is the centerpiece of the integration of an IT project. They must link developers, managers, IT security professionals, network engineers, and operational support teams. They are often part of all the different development stages, tests, and delivery [45][51][52]. Nevertheless, asses sing system administrators in either all or certain system development life cycle stages may warrant extended research because these subject matter experts can be a technical and operational bridge for IT projects abroad

Additionally, security culture may also be impacting additional cybersecurity attack methods. According to Asamoah, D., Nuertey, D., Agyei-Owusu, B., & Acquah, I. N. [46] there does exist a relationship between security culture and supply chain disruption occurrences. As a suggested future study, further analysis of supply chain attack occurrences and constructs used in this study (e.g. security culture) to analyze whether any significant relationships exist would be recommended for further research.

Lastly, such constructs mentioned is this paper in combination with newer threats, (e.g. supply chain attacks) are standalone variables in of themselves, yet could be interconnected to other growing vulnerabilities related to our national defense. There are technical advantages being safeguarded on the battlefield for the warfighter considered Critical Program Information (CPI). According to DoD 5200.39 [47] the entire life cycle of development of CPI needs to be continuous from the early stages of identification until needed throughout the SDLC to enforce such protections as tamper-proofing, exportability features, all forms of security, or mitigating countermeasures. The loss of data is one thing but the loss of a technical warfighter advantage as it relates to any modernization area (e.g. space, cyber, hypersonics, 5G, microelectronics, autonomy, biotechnology, directed energy, quantum science, networked communications and artificial intelligence) [49] [50] could have major impacts on national security thus affecting many lives [48]. Given this additional variable, security effectiveness could be similarly analyzed yet in this particular case assessing defense contractor key players of such protections of such technical advantages of the warfighter (e.g. government program managers, information security system engineers, security officers). A qualitative and quantitative assessment could be anonymously analyzed to understand how well security effectiveness results look given the audience is of DoD contractors that have products that were deemed to have CPI. The results of such a loss of CPI could result in a broader disadvantage that is felt politically and strategically for any country if an adversary has closed the gap or unexpectedly defeated such technological advantages as a result of any recovered or leaked CPI. Hence, this would not only lessen or eliminate the warfighters technical edge but would lessen or eliminate the economic advantages given the initial monetary investment into the technological advances.

6. CONCLUSION

In this study, a research model for assessing EF was reassessed against a previously vetted survey instrument that was designed to measure the constructs known as TM, AW, SC, TI and EF for the distinct purpose to assess non-CISSP opinions to broaden opinions and rule out potential bias from the more elite participants with CISSP certifications. The target audience criteria were ISACA members with at least 5 years of IT security experience and a bachelor’s degree with no participant having a CISSP certification. The objective was to determine whether significant correlations existed between each independent variable (TM, AW, SC, TI) and the dependent variable (EF). These relationships were analyzed using SEM and concluded that correlation assessments analyzed between these predictive constructs with EF were significant between SC and EF. Correlations were significant between AW and EF. Correlations were significant between TM and EF but not between TI and EF. These findings resulted in the rejection of the Ho1, Ho2 and Ho3 null hypotheses and the acceptance of Ho4 respectively.

Additionally, as a result of post hoc analysis using the PA technique of SEM, there were directpath associations from SC to EF observed, which reaffirmed previous research by Knapp and Ferrante [1]. This new respondent group for this study was specifically selected to decrease the bias in a security expert’s opinions in response to a suggested research extension criterion given by Knapp and Ferrante [1]. This was carried out by setting the respondent criteria to involve those who had not obtained any CISSP certifications. The results demonstrated that SC showed a significant relationship to EF and revealed significant correlations between SC, TM, and AW. Whether or not SC could be analyzed for mediation or TI for moderating effects should be assessed in future research. Moderation of TI and the mediation of SC was not in the scope of this study nor was it feasible due to a larger sample count to allow for an optimization of the findings.

There was no other significant correlation with the EF from any other predictive construct. Due to the importance of SC as a decisive predictor variable, it would be worth extending this research to pursue other constructs that could strengthen SC (e.g., using collaboration or communication methods) to account for other methodologies used for different projects or organizations.

In addition, a different target audience that is more inter twined among all the leading players in IT when it comes to security and operations could be a new population to target rather than ISACA members in general. One suggestion might be to assess system administrators using this same survey. Additionally, a reassessment of the good model fit check followed by conducting a CFA and PA could be done to compare or reaffirm relationships.

Any effort to reduce the edge that hackers have on IT infrastructures within organizations or across the industry could be offset by improving SC. The individuals that affect SC may not just be security personnel with the highest security certifications, but instead, other key players with a broader interaction and collaboration reach across an IT project (e.g., system administrators, system integration and test personnel). Some personnel may be more security biased than others, but those other vital roles still require proper security implementation, integration, and testing in their respective jobs. Primary constructs like SC or even major roles involved in the system or SDLC should not be ignored as possible hidden predictors or influencers of better EF.

If SC alone is a direct predictor of EF, research should target the SC improvement of the most influential players. For that matter, the standard system administrator or network administrator might be just as likely to assess or influence EF than a subject matter expert. An investment in SC improvements could prove to yield a massive ROI considering the financial ramifications of a successful cyberattack on any organization or industry worldwide.

Adding the diversity of non-CISSP participants as a pool to the sample solidifies previous studies’ notion that there are positive influences on EF across the board—not just from the perspective of participants that have CISSPs, but collectively from a greater pool of IT security professionals that make up a less-biased perspective. There are many jobs that require the CISSP and could very well make up a host of participants that have a wide knowledge of the security domain. However, studying only these individuals could neglect the valuable opinions of more common IT security participants. The fact that leadership, training, and culture routinely affect EF regardless of certification says the human factor is essential to achieving a higher degree of EF. Resources should be focused on improving these constructs with an ultimate objective to increase EF and not solely rely on technical means to achieve it across the entire IT industry in its war against cyber attacks. One promising approach is targeting research in areas where key roles that influence the effects of cybersecurity are analyzed with a higher degree of samples from

participants due to the fact that many key roles at the early stage of the SDLC do not require.

CISSP, therefore allowing for a higher sample size of more than adequate IT professionals without CISSP certifications

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

[1] Knapp, K. J., & Ferrante, C. J. (2014). Information security program effectiveness in organizations: The moderating role of task inter dependence. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 26(1), 27–46.

[2] Garg,V.,&Camp,L.J.(2015).Whycybercrime?ACMSIGCASComputersandSociety,45(2), 20–28.

[3] Rideout,T.(2016).Building a comprehensive strategy of cyber defense, deterrence, and resilience. The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, 40, 63.

[4] Stephens, J.F., &Tilton, M.W.(2017).Lawyers still lag behind in network and information security risk management: Clients and regulators demand more. The Brief, 46(4), 12.

[5] Woods,D.,Agrafiotis,I.,Nurse,J.R.,&Creese,S.(2017).Mappingthecoverageofsecurity controls in cyber insurance proposal forms. Journal of Internet Services and Applications, 8(1), 8.

[6] Choi, S., Martins, J.T., & Bernik, I.(2018). Information security: Listening to the perspective of organisational insiders. Journal of information science, 44(6), 752-767.

[7] Chen, Y., Ramamurthy, K., & Wen, K. (2015). Impacts of comprehensive information security programs on information security culture. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 55(3), 11–19.

[8] DaVeiga, A.(2016).Comparing the information security culture of employees who had read the information security policy and those who had not: Illustrated through an empirical study. Information & Computer Security, 24(2), 139–151.

[9] Humaidi, N., & Balakrishnan,V. (2018). Indirect effect of management support on users’ compliance behaviour towards information security policies. Health Information Management Journal, 47(1), 17– 27. [10] Karlsson, F., Åström, J., & Karlsson, M. (2015). Information security culture–state-of-the-art review between 2000 and 2013. Information & Computer Security, 23(3), 246–285.

[11] Parsons, K. M., Young, E., Butavicius, M. A., McCormac, A., Pattinson, M. R., & Jerram, C. (2015). The influence of organizational information security culture on information security decision making. Journal of Cognitive Engineering and Decision Making, 9(2), 117–129.

[12] Tang, M., Li, M., & Zhang, T. (2015;2016;). The impacts of organizational culture on information security culture: A case study. Information Technology and Management, 17(2), 179- 186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-015-0252-2

[13] Connolly, L.Y., Lang, M., Gathegi, J., & Tygar, D.J. (2017). Organisational culture, procedural countermeasures, and employee security behaviour. Information & Computer Security, 25(2), 118.

[14] Zailani, S. H., Seva Subaramaniam, K., Iranmanesh, M., & Shaharudin, M. R. (2015). The impact of supply chain security practices on security operational performance among logistics service providers in an emerging economy: Security culture as moderator. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management,45(7),652–673.

[15] Steinmetz, K., & Gerber,J. (2015). “It doesn’t have to be this way”:Hacker perspectives on privacy. Social Justice, 41(3(137)), 29–51.

[16] Ullah, F., Edwards, M., Ramdhany, R., Chitchyan, R., Babar, M. A., & Rashid, A. (2018). Data exfiltration:A review of external attack vectors and counter measures. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 101, 18–54.

[17] Zelle,A.R.,&Whitehead,S.M.(2014).Cyberliability:It’sjustaclickaway.Journalof Insurance Regulation, 33(6), 145–168.

[18] Evans, M., Maglaras, L.A.,He, Y., & Janicke, H.(2016). Human behavior as an aspect of cybersecurity assurance. Security and Communication Networks, 9(17), 4667–4679.

[19] Chin, A. G., Etudo, U., & Harris, M.A. (2016). On mobile device security practices and training efficacy: An empirical study. Informatics in Education, 15(2), 235. International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC) Vol.15, No.2, March 2023 102

[20] Bostan, A. (2016). Implicit learning with certificate warning messages on SSL webpages: What are they teaching? Security and Communication Networks, 9(17), 4295–4300.

[21] Farcasin, M., &Chan‐tin, E. (2015). Why we hate IT: two surveys on pre‐generated and expiring passwords in an academic setting. Security and Communication Networks, 8(13), 2361-2373.

[22] Iuga, C., Nurse, J.R., & Erola, A. (2016). Baiting the hook: Factors impacting susceptibility to phishing attacks. Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, 6(1), 8.

[23] Mahlaola, T.B., & VanDyk, B.(2016). Reasons for picture archiving and communication system (PACS) data security breaches: Intentional versusnon- intentional breaches. Journal of Interdisciplinary Health Sciences, 21(1), 271–279.

[24] Scholl, F. (2017). Government to be more engaged with security in 2017. CSO (Online),

[25] Medina, M. N., & Srivastava, S. (2016). The role of extraversion and communication methods on an individual’s satisfaction with the team. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 16(1), 78.

[26] Santos, C. M., Uitdewilligen, S., & Passos, A. M. (2015). Why is your team more creative than mine? the influence of shared mental models on intra-group conflict, team creativity and effectiveness. Creativity and Innovation Management, 24(4), 645- 658. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12129

[27] Nebel,S.,Schneider,S.,Beege,M.,Kolda,F.,Mackiewicz,V.,&Rey,G.D.(2017).You cannot do this alone! Increasing task interdependence in cooperative educational videogames to encourage collaboration. Educational Technology Research and Development, 65(4), 993–1014.

[28] Horstmeier, C.A., Homan, A.C., Rosenauer, D.,& Voelpel, S.C. (2016). Developing multiple identifications through different social interactions at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(6), 928–944.

[29] Von Bertanlanffy, L. (1950). An out line of general system theory. British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 1, 134–165.

[30] Bostrom, R.P., & Heinen, J.S.(1977). MIS problems and failures: A socio-technical perspective. Part I: The causes. MIS Quarterly, 1(3), 17–32.

[31] Malatji, M., Sune, V.S., & Marnewick, A. (2019). Socio-technical systems cybersecurity framework. Information and Computer Security, 27(2), 233–272.

[32] Ceesay,E.N.,Myers,K.,&Watters,P.A.(2018).Human-centeredstrategiesforcyber-physical systems security. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Security and Safety, 4(14), 154773– 154779. https://doi.org/10.4108/eai.15-5-2018.154773

[33] Sadok, M., Welch, C., & Bednar, P. (2020). A socio-technical perspective to counter cyber- enabled industrial espionage. Security Journal, 33 (1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-019-00198-2

[34] Adaba, G.B., & Kebebew, Y.(2018). Improving a health information system for real-time data entries: An action research project using socio-technical systems theory. Informatics for Health&SocialCare,43(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538157.2017.1290638

[35] Knapp, K. J., Marshall, T. E., Rainer Jr., R. K., & Ford, F. N. (2007). Information security effectiveness: Conceptualization and validation of at heory. International Journal of Information Security and Privacy, 1(2), 37–60.

[36] Bandura, A.(2001). Social cognitive theory: A nagentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

[37] Haqaf, H., & Koyuncu, M. (2018). Understanding key skills for information security managers. International Journal of Information Management, 43, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.07.013

[38] Furnell, S.(2021). The cybersecurity work force and skills. Computers & Security,100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.102080

[39] Wang, X., Wang, J. (2012). Structural Equation Modeling: Applications Using Mplus(3. Aufl. Ed.). Wiley.

[40] Nasir, A., Arshah, R.A., Hamid, M.R.A., & Fahmy, S. (2019). An analysis on the dimensions of information security culture concept: A review. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 44, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jisa.2018.11.003

[41] Burmeister, A., Li, Y., Wang, M., Shi, J., & Jin, Y. (2020). Team knowledge exchange: How and when does transformational leadership have an effect? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(1), 17- 31. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2411

[42] Beattie, K., Carson, B.P., Lyons, M.,& Kenny, I.C.(2017). The relationship between maximal strength and reactive strength. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 12, 548–553.

[43] Ulhas, K. R., Lai, J., & Wang, J. (2016). Impacts of collaborative IS on software development project International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC) Vol.15, No.2, March 2023 103 success in Indian software firms: A service perspective. Information Systems and eBusiness Management, 14(2), 315–336.

[44] Largent, D. (2016). Measuring and understanding team development by capturing self-assessed enthusiasm and skill levels. ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 16(2), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1145/2791394

[45] Mohino, D.V., Higuera, B.,& Montalvo, S. (2019). The application of a new secure software development life cycle (S-SDLC) with agile methodologies. Electronics, 8(11), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics8111218

[46] Asamoah, D., Nuertey, D., Agyei-Owusu, B., & Acquah, I. N. (2021). Antecedents and outcomes of supply chain security practices: The role of organizational security culture and supply chain disruption occurrence. The International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, ahead-ofprint(ahead-of-print)https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQRM-01-2021-0002

[47] Department of defense instruction 5200.39. (2020). https://esd.whs.mil/Directives/issuances/dodi/ [48] Office of the inspector general US department of defense., July 22, 2022 report no. dodig-2022- 113https://media.defense.gov/2022/Jul/26/2003042087/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2022-113.PDF

[49] Phibbs, Christina L., and Rahman, Shawon S. M. 2022. “A Synopsis of “The Impact of Motivation, Price, and Habit on Intention to Use IoT-Enabled Technology: A Correlational Study”, Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, Special Issue Cyber-Physical Security for Critical Infrastructures, 2, no. 3: 662-699. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp2030034

[50] [50] Roberts, Gerrianne and Rahman, Shawon S. M., Does Digital Native Status Impact End-User Antivirus Usage? (May 19, 2021). International Journal of Computer Networks & Communications (IJCNC), Vol.13, No.2, March 2021, DOI: 10.5121/ijcnc.2021.13207

[51] Schneider, Marvin and Rahman, Shawon “Protection Motivation Theory Factors that Influence Undergraduates to Adopt Smartphone Security Measures ”; International Journal of Information Technology in Industry (ITII), Vol 9, No 1 (2021)

[52] Loukaka, Alain and Rahman, Shawon; “Security Professionals Must Reinforce Detect Attacks to Avoid Unauthorized Data Exposure”; International Journal of Information Technology in Industry (ITII), vol. 8, no.1, 2020

[53] Alshammari, Tahani and Alserhani, Faeiz; “Scalable and Robust Intrusion Detection System to Secure the IoT Environments using Software Defined Networks (SDN) Enabled Architecture”; International Journal of Computer Networks and Applications (IJCNA), vol. 9, no.6, 2022

AUTHORS

Dr. Joshua A. Porche is an Engineering Manager for Mission Avionics in the

Cyber Department under the Space and Airborne Systems division at L3Harris

Corporation. Dr. Porche is also a Senior Master Sergeant in the United States

Airforce Reserves as a Cyber Defense Operations Superintendent for the 36

Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron within the 403rd Wing at Keesler AFB, MS.

Dr. Porche’s prior experience in cybersecurity in the military was a member of the 236th Combat Communications Squadron in Hammond, La. for the Louisiana Air National Guard and subsequently in the 114th Space Control Squadron at Patrick AFB, Fl. for the Florida Air National Guard. Dr. Porche previously was a Systems Integration & Test Engineer at the Harris Corporation and transitioned into becoming an Information Security Systems Engineer. Dr. Porche has his Secure+ certification and EE from Southern University. Dr. Porche has extensively managed the NIST Risk Management Framework across a multitude of programs within the DoD and DoC for both classified and unclassified programs to include all branches of service and other government agencies. His research interest includes security effectiveness, moving target defense technology, and providing path diversity for secure communications on the battlefield. He has earned his Ph.D. in Information Technology with a specialization in Security and Information Assurance from Capella University.

Dr. Shawon S. M. Rahman is a Professor in the Department of Computer

Science and Engineering at the University of Hawaii Hilo. His research interests

include Cybersecurity, software engineering education, information assurance and

security, web accessibility, cloud computing, STEM, software testing, and quality assurance. He has published over 130peer-reviewed papers and mentored numerous students and at least 60 have published their first peer-reviewed publication by co-authoring with him. Dr. Rahman is serving as the Member-atlarge and Academic Advocate: Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo and Academic Advocate of the IBM Academic Initiative. He is an active member of many professional organizations, including IEEE, ACM, ASEE, ASQ, and UPE.